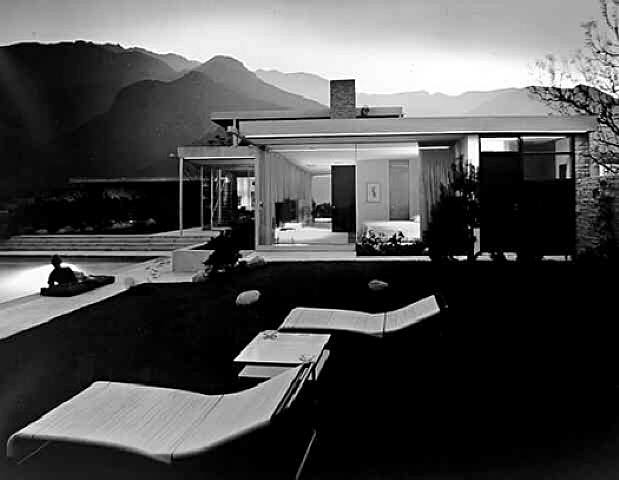

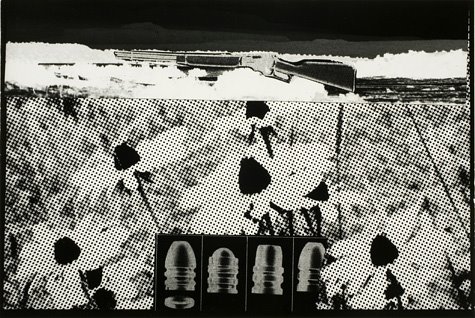

JTF (just the facts): A total of 32 works by nine different artists, hung in a single gallery space with a dividing wall. All of the works come from the period 2000-2009, with most made in the last year or so. The exhibit was curated by Amani Olu. (Installation shots at right.)

JTF (just the facts): A total of 32 works by nine different artists, hung in a single gallery space with a dividing wall. All of the works come from the period 2000-2009, with most made in the last year or so. The exhibit was curated by Amani Olu. (Installation shots at right.)

The following artists have been included in the show, with the number of works on display in parentheses and background details on the prints afterward:

- Michael Bühler-Rose (3): Framed in white with no mat; 8×10, acrylic on photogram

- Talia Chetrit (8): Framed in black with no mat; 8×10; gelatin silver contact prints, in editions of 4+1

- Matthew Gamber (4): Not framed; 40×50; archival inkjet prints; in editions of 3

- Stephen Gill (1): Artist book, unfolded to show 18 images; pinned to wall with no frame; in edition of 1000

- Adrien Missika (4): Taped directly to wall with no frame; 8×12; screen prints on paper; in editions of 5

- Pushpamala N (4): Framed in black with no mat; 5.75×8; C prints on metallic paper; in unlimited editions

- Noel Rodo–Vankeulen (1): Running loop of animated GIFs on screen; in edition of 10

- Arthur Ou (3): Framed in grey metal with no mat; 51×40; archival pigment prints on silver rag tape; in editions of 4+1

- Michael Vahrenwald (4): Framed in black with no mat; 16×24; gelatin silver prints; in editions of 5+2

Comments/Context: In a photography world recently and overwhelmingly dominated by digital color, the rightful place for work done in black and white is still unsettled. In just a few short years, making monochrome photographs has become a contrarian act, an overt rejection of the mainstream. For many, this rebellion is nostalgia in hiding, a desire to go back to the old, classic ways that we have loved for so long. But for others, using black and white represents a bolder and surprising step forward, a movement beyond the homogeneity of color and the search for something altogether new.

Comments/Context: In a photography world recently and overwhelmingly dominated by digital color, the rightful place for work done in black and white is still unsettled. In just a few short years, making monochrome photographs has become a contrarian act, an overt rejection of the mainstream. For many, this rebellion is nostalgia in hiding, a desire to go back to the old, classic ways that we have loved for so long. But for others, using black and white represents a bolder and surprising step forward, a movement beyond the homogeneity of color and the search for something altogether new.

The group show now on at Bose Pacia gathers together a sampling of photographers who are testing this new boundary, using black and white as an element of more conceptual work. The standouts in this show (for us) are Matthew Gamber, Stephen Gill, and Talia Chetrit; many of the others seemed a bit forced – trying too hard or still struggling to refine their ideas into something truly novel.

Matthew Gamber makes images of empty, erased chalkboards. From a distance, they appear rubbed and washed, the slate color tinged with remnants of white. Up close, the boards are covered in minute scratches and scrapes, smudges and tape residue, creating a historical record of wear and tear (or perhaps the scene of a ritual erasing of a Cy Twombly). Overall, they are hauntingly meditative and quiet.

Stephen Gill’s artist book A Series of Disappointments creates a typology like conceptual framework for the infinite variety found in losing betting slips. They are crumpled and crushed, folded and balled, ripped and twisted, all discarded. Photographed against a neutral grey background, they become a kind of delicate origami of loneliness and despair.

Talia Chetrit’s Photoshop gradients bring to mind the nuanced experiments with light of Luisa Lambri. The best of these abstract works play with the edges of tonality, adding an element of cool refinement to color field painting. This type of camera-less Photoshop art seems to signal a big open space for artists to explore (Cory Arcangel is another artist/photographer working in this mode), the new technology asking and requiring artists to make new innovative art, rather than making the same old pictures in new ways. In just a few years, I expect we’ll see an entire subcategory of this kind of work.

Overall, this is a well edited show that provides a thoughtful array of new black and white work. While I’m not sure it delivers a satisfyingly complete answer for what comes “after color”, it certainly provides some potential signposts for where to look for the answers.

Collector’s POV: None of the emerging artists in this show have any meaningful secondary market, so collectors will need to consider gallery retail as the only available option for acquiring the work. A quick rundown on the generally reasonable prices:

- Michael Bühler-Rose: $800 each

- Talia Chetrit: 8 images sold as a set for $6400

- Matthew Gamber: $4500 each

- Stephen Gill: $350 for book

- Adrien Missika: $850 each

- Pushpamala N: $300 each

- Noel Rodo–Vankeulen: $280

- Arthur Ou: $6000 each

- Michael Vahrenwald: $2000 each

Rating: * (one star) GOOD (rating system described here)

Transit Hub:

- Stephen Gill artist website (here)

- Matthew Gamber artist website (here)

- Talia Chetrit artist website (here)

- Flavorwire interview with Amani Olu (here)

- Amani Olu website (here)

- Charlotte Cotton: The New Color: The Return of Black-and-White (here)

After Color: Curated by Amani Olu

Through August 21st

Bose Pacia

508 West 26th Street

New York, NY 10001