JTF (just the facts): A total of 306 black and white photographs, alternately framed in white and black and matted, and hung in a series of 8 rooms on the sixth floor of the museum. The works span the period between 1929 and 1989. The entry to the exhibit contains a collection of large scale color maps that chart the photographer’s worldwide travels in meticulous detail. There are 5 glass vitrines scattered throughout the exhibit (each running the length of an entire wall) containing magazine spreads. Two large seating areas (tables/chairs) stand at the center of the exhibit, with exhibition catalogues available for further review.

JTF (just the facts): A total of 306 black and white photographs, alternately framed in white and black and matted, and hung in a series of 8 rooms on the sixth floor of the museum. The works span the period between 1929 and 1989. The entry to the exhibit contains a collection of large scale color maps that chart the photographer’s worldwide travels in meticulous detail. There are 5 glass vitrines scattered throughout the exhibit (each running the length of an entire wall) containing magazine spreads. Two large seating areas (tables/chairs) stand at the center of the exhibit, with exhibition catalogues available for further review.

After 4 images in the entry hall and 6 images used to show differences in printing techniques, the exhibit is divided into 13 discrete sections, which wind around in a rough figure eight pattern across the various rooms, using different colors of grey paint to set off different areas. The titles of these sections (which are slightly different than those in the exhibition catalog in some cases) are listed below, with the number of images on view in each in parentheses:

- Early Years (34)

- After the War, End of an Era (21, with 1 case)

- Old Worlds: East (13)

- Old Worlds: West (22)

- Old Worlds: France (17)

- New Worlds: USA (22, with 1 case)

- New Worlds: USSR (17, with 1 case)

- Photo Essay: The Great Leap Forward, China, 1958 (37, with 1 case)

- Photo Essay: Bankers Trust Company, New York, 1960 (15)

- Portraits (34)

- Beauty (10)

- Encounters and Gatherings (26)

- Modern Times (28, with 1 case)

The show was organized and curated by Peter Galassi, Chief Curator of Photography at MoMA. After its run in New York, the exhibit will travel to the Art Institute of Chicago, SFMOMA, and the High Museum in Atlanta. A detailed exhibition catalog, with a thoughtful and well-researched scholarly essay by Galassi and detailed background information (including the maps), is available from the museum for $50 or $75, depending on the binding (here). (Unfortunately, no photography was allowed in the exhibit, so there are no installation shots for this show.)

Comments/Context: As you make your way to the top of the escalator on the sixth floor of the MoMA, if you can block out the chaos of the gift shop, the audioguide station, and the thronging crowds for a moment, the staggering floor to ceiling maps of Henri Cartier-Bresson’s worldwide travels as a photojournalist will come into view. While you might be tempted to rush into the galleries to see the photography, I’d suggest taking a moment to let these hopelessly detailed maps wash over you a bit, to take in the multi-colored squiggling lines that criss-cross the continents decade after decade, and to consider the many challenges Cartier-Bresson faced in both getting from one far flung exotic or politically charged locale to the next, and in making his pictures when he got there.

Like many collectors I expect, I have become almost overexposed to the artist’s best known images. But the real life context of the maps reminded me of how much more to the story there really was beyond the early greatest hits, and just how hard it was going to be from a curatorial standpoint to both capture all that he did in his long career and somehow organize it into an easily communicated shorthand. Curator Peter Galassi has done his best to weave various threads together, alternating between chronological, geographic, structural, and thematic approaches in presenting the works, creating a interlocking brocade of ideas. But in the end, Cartier-Bresson remains more elusive than you might expect; the “decisive moment” tells part of the story, but certainly not all of it, and even the best organizational intentions left me with a sense of wondering how it all should fit together.

The exhibition begins chronologically with Cartier-Bresson’s early 1930s work, and these pictures strongly stand out in terms of their Modernist, avant–garde and Surrealist influences. The first room contains many of the photographer’s best known and most innovative vintage images, and together, they feel like a fresh, self-contained body of work, rooted more in compositional experimentation, literature, and left-wing politics than in what we now call photojournalism. As I moved into subsequent rooms, I was struck by how Cartier-Bresson seemed to leave this aesthetic behind, or perhaps to refine it for more everyday use, moving more toward neutral observation and away from conscious aesthetic exploration.

After a room of images from the post-WWII period, Cartier-Bresson’s output is roughly grouped by geography, selecting single images from different decades and assignments, loosely sorted into a “before and after” of old and new worlds. Images of Asia, Europe, and France in particular chronicle pre-industrial cultures, while shots of the US and USSR document economic expansion and growth. Galassi then does a deep dive into two photo essays (one of the Great Leap Forward in China and one of financial workers at Bankers Trust), trying to show the more detailed process and context in Cartier-Bresson’s single subject projects – long captions add an unexpected level of reporting background, while multiple images help to tell a narrative with more vantage points. The final sections of the show are then grouped thematically by subject matter, starting with a large collection of portraits, and ending with images of crowds and modern society.

In virtually all of the work after the second World War, all the way through into the 1970s, Cartier-Bresson was remarkably consistent in his crafting of photojournalistic vignettes. Most pictures are a self-contained story, often capturing subtle social cues, glances, and gestures that have coalesced into a composition that captures the juxtaposition of different people. Whether in India or France, China or the US, he was able to reduce the chaos around him into clear relief, highlighting the figures and their cultural interrelationships. Expressions, facial emotions, fleeting encounters, and unexpected action form the basis of virtually all of his best images.

On one hand, seeing hundreds of these images can make them seem a bit formulaic, but in the context of those maps at the beginning, I saw his repeated search for certain themes and ways to construct a picture as mechanisms for simplifying the unusual situations and tough challenges he continually encountered all over the globe. It seems he had already discovered how to be successful in telling the kinds of stories he wanted to tell, and he refined his eye and approach to fit his needs over the long decades of his career. It was all a matter of moving and waiting until the moment was right; it sounds so effortless, but a massive show likes this is proof that it took an enormous amount of dedication to his craft.

Overall, this retrospective does a fine job of providing a larger framework for considering Cartier-Bresson. It successfully forced me to get beyond his iconic early work, to appreciate a broader sample of his images from various decades, and to see patterns and evolutions in his style. That said, I can’t help wondering if many more targeted exhibitions will now be necessary to really unravel the complexities of his work between 1945 and 1975; the narrative still seems messy and unfinished. But perhaps this is the mark of a thought-provoking exhibition: it provides some of the answers, but leaves many more open-ended clues and puzzles for future study.

Collector’s POV: Cartier-Bresson’s prints are ubiquitous at auction, with dozens of prints available each and every season. Prices have ranged from $1000 to $200000 in recent years; obscure images and later prints are generally at the bottom end of that range, with vintage prints of the iconic images at the top. That said, even later prints of his most famous works are now regularly pricing above $10000, so prices continue to inch upward. Active collectors of Cartier-Bresson’s work shouldn’t miss the small selection of prints at the beginning of the show that highlights the differences in prints made by the photographer and various labs over the years. I was interested to learn that early prints made by the photographer himself were very muted in tone, and that later prints have black borders and are signed on the front, a handy heuristic for auction previews and the like.

Rating: *** (three stars) EXCELLENT (rating system described here)

Transit Hub:

- Exhibition site (here)

- Reviews: NY Times (here), New Yorker (here), Daily Beast (here), Wall Street Journal (here)

- Charlie Rose interview with Galassi, Frank and Sire (here)

- Fondation Henri Cartier-Bresson (here)

- Magnum Photos page (here)

Henri Cartier-Bresson: The Modern Century

Through May 22nd

The Museum of Modern Art

11 West 53rd Street

New York, NY 10019

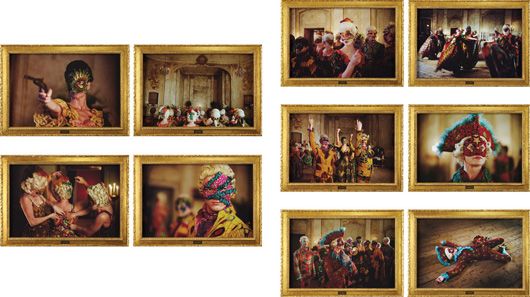

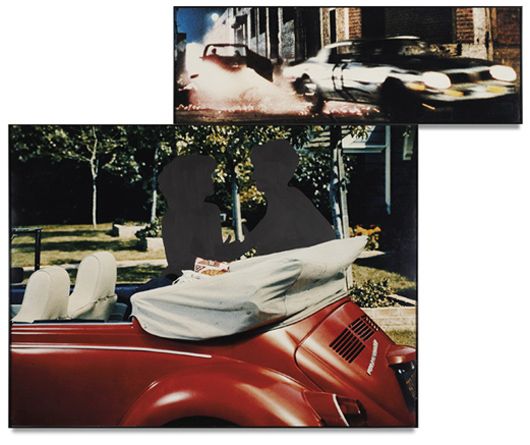

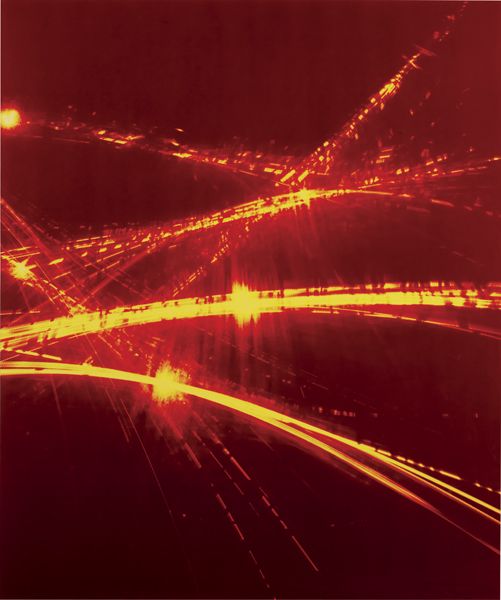

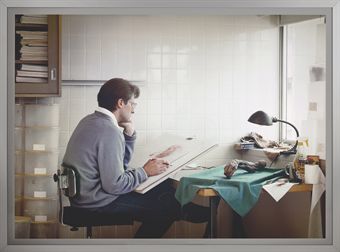

JTF (just the facts): A total of 22 color photographs, framed in white with no mat, and hung in the atrium gallery space at the top of the store. All of the works are chromogenic prints made between 2007 and 2010. The prints on display are each 24×20 or reverse, made in editions of 12+2. A larger size is also available, 40×33 or reverse, in editions of 3+2. (Installation shots at right.)

JTF (just the facts): A total of 22 color photographs, framed in white with no mat, and hung in the atrium gallery space at the top of the store. All of the works are chromogenic prints made between 2007 and 2010. The prints on display are each 24×20 or reverse, made in editions of 12+2. A larger size is also available, 40×33 or reverse, in editions of 3+2. (Installation shots at right.) While at first glance, some of these images have the look of large format family snapshots, the overall effect is often a wonderfully strange and awkward moment, where cultures clash, invisible boundaries are reluctantly crossed, and stereotypes are broken down. A closer look reveals unexpected connections between these people, where ethnicities, ages, genders, and personality types seem to melt away, and honest and authentic emotions seem to come through. The gestures run the gamut from stiff and wooden to tender and moving, exposing an entire spectrum of subtle social interaction.

While at first glance, some of these images have the look of large format family snapshots, the overall effect is often a wonderfully strange and awkward moment, where cultures clash, invisible boundaries are reluctantly crossed, and stereotypes are broken down. A closer look reveals unexpected connections between these people, where ethnicities, ages, genders, and personality types seem to melt away, and honest and authentic emotions seem to come through. The gestures run the gamut from stiff and wooden to tender and moving, exposing an entire spectrum of subtle social interaction. Collector’s POV: While this isn’t a selling show, prints from this series are available directly from the artist (linked below). The 24×20 prints start at $2500 and escalate to $5000 based on the place in the edition. The 40×33 prints start at $4500 and escalate to $6000. Renaldi’s work has not yet surfaced in the secondary markets, so interested collectors will need to follow up at gallery retail or directly with the artist.

Collector’s POV: While this isn’t a selling show, prints from this series are available directly from the artist (linked below). The 24×20 prints start at $2500 and escalate to $5000 based on the place in the edition. The 40×33 prints start at $4500 and escalate to $6000. Renaldi’s work has not yet surfaced in the secondary markets, so interested collectors will need to follow up at gallery retail or directly with the artist.