While we often talk about art as an asset class (in the financial sense), the fact remains that given the uniqueness of the objects being traded and their general illiquidity, it’s nearly impossible to find ways to bet on the “market” without going “long” (via a buy and hold strategy) on certain artists or specific works. There really are no synthetic financial instruments that can be used to mimic the behavior of the art markets, no ways to “short” certain artists, or to buy insurance against volatility in art prices. After recently reading Michael Lewis’ The Big Short and diving into the weeds of credit default swaps and collateralized debt obligations as applied to the subprime mortgage market, my head has been swimming with unrealistic ideas for finding a way to create a financial instrument that could encompass the world of contemporary photography.

So here’s a thought experiment. Suppose you are a financial investor looking to get exposure to contemporary photography as a niche asset class. You are not interested in visiting gallery shows, looking at pictures, talking to gallery owners, or “buying what you love”. You instead want to objectively place a financial bet on the prospects of contemporary photography, as it seems like a “hot” market that might outperform other asset classes, if you only knew how to access it.

Let’s say that you heard about this site and decided that you would use the data provided here to generate “trade” ideas. If you went back through the 170+ reviews we did in 2009 and strip out all the museum shows (not for sale) and the exhibits of vintage work (not new/contemporary), you’d be left with a rated list (one to three stars) of the world of New York contemporary photography for the year (potentially a biased snapshot, but hopefully grounded in some reality, and far better than any you could generate on your own). If you then selected the top ten (or so) shows and purchased one print from each show, you might have a decent proxy (or “market basket”) for the best of what was available in 2009. Sure, there are differences in quality between the works in any one show, but let’s gloss over those for a moment and assume that a solid, representative work can be chosen from what was on view. And sure, we can have real arguments about whether the show ratings are accurate, but since you have no effective way to second guess the ratings (and no real interest in doing so), you are really just executing on what you have been given.

Taking this as a structural model, you then extrapolate this to a ten year fund vehicle (similar to a venture capital fund), five years of buying/investing in the work, and five years of “harvesting” (waiting to liquidate the images, via selling privately or in the auction market). Thus, in its minimum incarnation, the ultimate fund has approximately 50 diverse works from as many as 50 artists from a 5 year period. You then build a ladder of funds for each 5 year period of art.

If you followed the above instructions, here’s what the 2009 DLK COLLECTION market basket for contemporary photography would have looked like (in alphabetical order):

1 Roger Ballen, 20×20, from Boarding House (Gagsoian)

1 Edward Burtynsky, 40×50, from Oil (Hasted Hunt Kraeutler)

1 Doug DuBois, 20×24, from All the Days & Nights (Higher)

1 Lee Friedlander, 16×20, from Still Life (Janet Borden)

1 Beate Gütschow, 36×31, from series of constructed cities (Sonnabend)

1 Sally Mann, 15×14, from Proud Flesh (Gagosian)

1 Walter Niedermayr, 50×100, from series of mountains/ski resorts (Robert Miller)

1 Nicholas Nixon, 11×14, from Old Home, New Pictures (Pace/MacGill)

1 Alec Soth, 32×40, from The Last Days of W. (Gagosian)

1 Kehinde Wiley, 24×20, from Black Light (Deitch)

This basket, as a whole, would have cost almost exactly $100000 last year. It covers both black and white and color, straight and manipulated, large scale and smaller sizes. If investors in this fund wanted to invest more than $100000 each year, simply multiply the investment out, buying say 5 prints from each show instead of 1 ($500000 a year invested in 50 pictures rather that $100000 in 10). This would avoid the temptation to dilute the pool by adding images from further down the list of shows. Year to year, there would of course be variation in the cost of the basket based on the arrival rate of great work, but I’m guessing it would likely even out over time.

The returns of the fund would follow a similar path as the “j-curve” of venture capital. Immediately after purchasing the works, their actual market value would fall, as a retail premium is paid before any lasting value is created. (The value of the works could in theory be “marked to market” by using comparative auction results.) The value of the images would likely slowly build over time, with some “winners” growing faster than others, driving the ultimate return on the whole pool of images. Was 2009 a “good vintage” for contemporary photography or not? It’s too early to tell.

To me, all of this seems utterly plausible, in a ruthlessly financial sense.

From other vantage points, I think this whole concept raises a few tangentially interesting ideas, even for those who are not particularly financially minded.

- Suppose you are a wealthy person who has hired a “photography consultant” to assist you in choosing what to buy for your collection. You are paying this person a fee for their services. If you were interested in building a contemporary collection, how were his/her recommendations different than what I’ve proposed? Did you buy the prints on the list above? And if not, why not, and what did you buy instead, and why?

- Suppose you are on a museum acquisitions committee for photography, and you have a decent sized budget to spend on recent contemporary work. How did what you actually bought in 2009 match with the list above? Did you actually talk through all of these and actively dismiss them?

In both cases, I’d be tempted to slap this list down and force some real discussion about why you made the buying choices you did. Not because your aim is to maximize your financial return on contemporary photography (it almost certainly isn’t in these two cases), or because our ratings are somehow all-knowing, but because the exercise of talking through the choices and trade-offs would be worthwhile. And of course, if you change your mind, it is altogether possible to still “buy into” this 2009 “trade”, although prices may have already started to rise, diluting your eventual returns.

For you money managers out there, I’d be interested to hear how you might improve on this fanciful idea or if someone else is already doing it. By the way, I also think there is the potential for an “event-driven” investment vehicle for photography as well, driven by upcoming retrospectives, artist deaths, and other major market movers; but we’ll save that for another day.

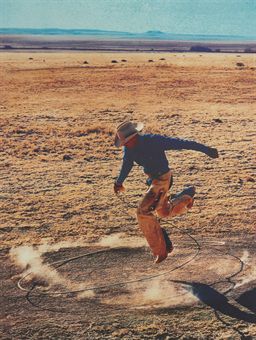

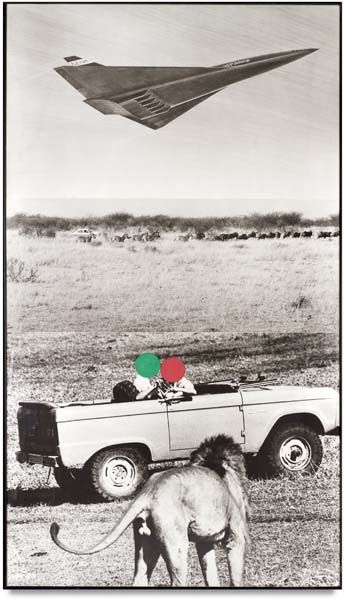

The photographs in the various Contemporary Art auctions at Phillips last week delivered more mixed results than those in the preceding sales at Christie’s and Sotheby’s. While the Total Sale Proceeds did cover the low estimate, the buy-in rate was over 35%. Dennis Hopper’s works performed well beyond expectations, perhaps signalling a run-up ahead of his MOCA show this summer.

The photographs in the various Contemporary Art auctions at Phillips last week delivered more mixed results than those in the preceding sales at Christie’s and Sotheby’s. While the Total Sale Proceeds did cover the low estimate, the buy-in rate was over 35%. Dennis Hopper’s works performed well beyond expectations, perhaps signalling a run-up ahead of his MOCA show this summer. 81.03% of the lots that sold had proceeds in or above the estimate range. There were a total of 6 surprises in this sale (defined as having proceeds of at least double the high estimate):

81.03% of the lots that sold had proceeds in or above the estimate range. There were a total of 6 surprises in this sale (defined as having proceeds of at least double the high estimate):