JTF (just the facts): Published in 2000 by De Verbeelding. 72 pages, with 33 black and white images. Each image is a 2 page panorama. Includes an essay by the artist. (Cover shot at right.)

JTF (just the facts): Published in 2000 by De Verbeelding. 72 pages, with 33 black and white images. Each image is a 2 page panorama. Includes an essay by the artist. (Cover shot at right.)

.

JTF (just the facts): Published in 2000 by De Verbeelding. 72 pages, with 33 black and white images. Each image is a 2 page panorama. Includes an essay by the artist. (Cover shot at right.)

JTF (just the facts): Published in 2000 by De Verbeelding. 72 pages, with 33 black and white images. Each image is a 2 page panorama. Includes an essay by the artist. (Cover shot at right.)

While certainly any collector’s definition of a good auction is one that includes the specific material that interests him/her, I must admit that beyond our personal affinities, I thoroughly enjoy single owner sales. I think that this is because I am intensely interested in the process of collecting, of how collectors weigh options and make choices, how they search, and hunt, and look, and educate themselves, eventually culminating in laying down their hard earned money for those certain images that move them the most. Every single collection is a unique gathering, the objects often connected by less than obvious ideas and emotional responses. I also think there is a lot to be learned from collectors who have been at it for decades; this is why we are always searching out experienced collectors who will talk with us, and tell us their secrets, even if our tastes for work are entirely different. The parallels are not in the end points, but in the thinking in between.

While certainly any collector’s definition of a good auction is one that includes the specific material that interests him/her, I must admit that beyond our personal affinities, I thoroughly enjoy single owner sales. I think that this is because I am intensely interested in the process of collecting, of how collectors weigh options and make choices, how they search, and hunt, and look, and educate themselves, eventually culminating in laying down their hard earned money for those certain images that move them the most. Every single collection is a unique gathering, the objects often connected by less than obvious ideas and emotional responses. I also think there is a lot to be learned from collectors who have been at it for decades; this is why we are always searching out experienced collectors who will talk with us, and tell us their secrets, even if our tastes for work are entirely different. The parallels are not in the end points, but in the thinking in between.

Total High Lots (high estimate above $50000): 9

JTF (just the facts): Published by the artist in 2008. Unpaginated, with 36 color images. Includes an essay by Bob Frommé and a detailed biography. (Cover shot at right, via Photo Eye.)

JTF (just the facts): Published by the artist in 2008. Unpaginated, with 36 color images. Includes an essay by Bob Frommé and a detailed biography. (Cover shot at right, via Photo Eye.)

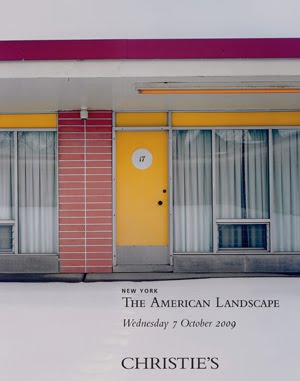

Christie’s various owner photography sale takes to heart the learnings of real estate developers who build shopping malls: the key is getting the anchor tenants, and then the rest of the specialty shops will be enhanced by the presence of the big names. This auction is centered on a solid group of iconic images that will pique the interest of a broad spectrum of collectors: a full set of Curtis’ The North American Indian, a vintage De Meyer Water Lilies, a vintage Kertész The Stairs of Montmartre, a vintage Alvarez Bravo El Ensueño (the cover lot), a Strand portrait of Rebecca, two solid Franks, and an Eggleston “red ceiling”. These lots are spread across the sale, with the rest of the material (a mix of the usual suspects and a few surprises) in between. Overall there are a total of 139 lots on offer, with a total High estimate of $4740000. (Catalog cover at right.)

Christie’s various owner photography sale takes to heart the learnings of real estate developers who build shopping malls: the key is getting the anchor tenants, and then the rest of the specialty shops will be enhanced by the presence of the big names. This auction is centered on a solid group of iconic images that will pique the interest of a broad spectrum of collectors: a full set of Curtis’ The North American Indian, a vintage De Meyer Water Lilies, a vintage Kertész The Stairs of Montmartre, a vintage Alvarez Bravo El Ensueño (the cover lot), a Strand portrait of Rebecca, two solid Franks, and an Eggleston “red ceiling”. These lots are spread across the sale, with the rest of the material (a mix of the usual suspects and a few surprises) in between. Overall there are a total of 139 lots on offer, with a total High estimate of $4740000. (Catalog cover at right.)

Here’s the breakdown:

There are certainly plenty of lots to interest us this sale, though many of them are clearly out of reach in terms of our budget. Below is a selection of images that caught our eye, regardless of price or exact fit with our collection:

There are certainly plenty of lots to interest us this sale, though many of them are clearly out of reach in terms of our budget. Below is a selection of images that caught our eye, regardless of price or exact fit with our collection:Lot 708 Walker Evans, Saratoga, 1931

Lot 724 Lee Friedlander, Butte, Montana, 1970/1973

Lot 755 Lee Friedlander, New Orleans, 1969/Later

Lot 774 Malick Sidibé, Les Trois Amis, 1968

Lot 798 Thomas Struth, Washington Street, New York/Tribeca, 1978

Lot 811 Paul Strand, Rebecca Strand, New York, 1922/1950s

Lot 819 Baron Adolph De Meyer, Water Lilies, c1906 (at right, bottom)

Lot 831 Nan Goldin, Red Sky from My Window, NYC, 2000

The complete lot by lot catalog can be found here. The eCatalogue is located here.

Photographs

October 8th

Christie’s

20 Rockefeller Plaza

New York, NY 10020

Lots of action over at Hasted Hunt (here) these days:

Wow!

(via Lindsay Pollock here)

The celebrated French photographer Willy Ronis died over the weekend at the age of 99. Ronis made romantic, humanist images of postwar France, in a tradition and style similar to Doisneau, Brassai and Kertesz.

The celebrated French photographer Willy Ronis died over the weekend at the age of 99. Ronis made romantic, humanist images of postwar France, in a tradition and style similar to Doisneau, Brassai and Kertesz.

While Ronis made many memorable images of Paris city life, perhaps his most famous picture is Le Nu Provençal, Gordes from 1949 (at right, via Afterimage Gallery (here)). As collectors of female nudes, we have considered this image for years; given its tremendous overexposure, the work now verges on being a cliché. And yet, there’s an obvious reason why so many people love it; the simple form, the delicate composition, and the beautiful light streaming in from the open window come together to make a quietly elegant scene.

While most images by Ronis are somewhat affordable at auction (under $3000), Le Nu Provençal, Gordes, will likely set you back double that, perhaps more at retail, depending on the size of the print. And while I’m not clear on who might officially represent him/his estate at this point, it appears that in addition to Afterimage, both Monroe Gallery (here) and Jackson Fine Art (here) carry a decent selection of Ronis inventory.

Christie’s begins its busy Fall photography season with a selection of color photographs from the collection of Bruce and Nancy Berman. Many collectors will remember that the public dismantling of this collection began last Fall, with a very successful sale devoted entirely to William Eggleston (preview here, results here). The group of images up for sale now also has a heavy dose of Eggleston’s work, mixed with a variety of other well known photographers who have documented vernacular American architecture/life (mostly small town/rural) in its various forms; many of these images were on view at the Getty in 2006 (here).

Christie’s begins its busy Fall photography season with a selection of color photographs from the collection of Bruce and Nancy Berman. Many collectors will remember that the public dismantling of this collection began last Fall, with a very successful sale devoted entirely to William Eggleston (preview here, results here). The group of images up for sale now also has a heavy dose of Eggleston’s work, mixed with a variety of other well known photographers who have documented vernacular American architecture/life (mostly small town/rural) in its various forms; many of these images were on view at the Getty in 2006 (here).

Even though we have virtually no color in our collection at the moment, there is plenty to tempt us in this sale. Here are some of the highlights from our perspective.

Even though we have virtually no color in our collection at the moment, there is plenty to tempt us in this sale. Here are some of the highlights from our perspective. The second of Phillips’ themed sales comes in early October and covers Latin America, broadly defined. It includes artists and photographers from Central America, South America, Spain, Mexico, and Cuba, along with others who made images in those regions. There are a total of 78 lots of photography on offer, with a total High estimate of $836700. (Catalog cover at right.)

Here’s the breakdown:

Total Low Lots (high estimate up to and including $10000): 59

Total Low Estimate (sum of high estimates of Low lots): $315700

Total Mid Lots (high estimate between $10000 and $50000): 17

Total Mid Estimate: $351000

Total High Lots (high estimate above $50000): 2

Total High Estimate: $170000

The top lot by High estimate is lot 192, Vik Muniz, Maria Callas (from Diamond Divas), 2004 at $70000-90000.

Here’s a list of all the photographers who are represented by more than one lot in the sale (with the number of lots on offer in parentheses):

Manuel Alvarez Bravo (9)

Luis Gonzalez Palma (6)

Tina Modotti (5)

Mauricio Alejo (3)

Vik Muniz (3)

Miguel Rio Branco (2)

Lola Alvarez Bravo (2)

Marta Maria Perez Bravo (2)

Martin Chambi (2)

Graciela Iturbide (2)

Alberto Korda (2)

Leo Matiz (2)

Enrique Metindes (2)

Mario Cravo Neto (2)

Edward Weston (2)

Marina Yampolsky (2)

While there weren’t too many great fits for our collection, we did like lot 54 Tina Modotti, Untitled (corn), 1920s.

The complete lot by lot catalog can be found here.

Latin America

October 3rd

Phillips De Pury & Company

450 West 15 Street

New York, NY 10011

In honor of the opening of the new Fall season of photography, I thought I would do something last night that I don’t do particularly often: take a spin through a series of gallery openings. The primary reason we tend to pass on most openings is that they are the single worst time to see an art exhibition: the crowds severely reduce the likelihood of seeing or understanding the images on view. But as another collector recently reminded me, the main reason to show up is not to see the art, but to show support for the artists and galleries and to reinforce for them that at least some collectors are paying attention.

So I chose a group of five openings to visit last night, spanning a show of vintage prints from an early 20th century master (long dead and who didn’t attend) to a first gallery show in New York for an emerging contemporary photographer (clearly alive and who did), with a few in between. In many ways, my goal was primarily to take the pulse of the market and get a feel for the overall mind set of the collecting public. We’ll go back to each of the shows we visited last night for a more formal review, so our comments here are aimed more at the quality/quantity of the visitors than the quality of the art.

The Jacques Henri Lartigue opening at Howard Greenberg (here) and the Nicholas Nixon opening at Pace/MacGill (here) had a generally common feel: civilized and refined art viewing for a select group, with well known collectors comfortably conversing with each other and the gallery staff in hushed tones. Both shows attracted a generally older but sophisticated looking crowd; I was certainly on the younger half of the age distribution. While all openings work hard to be welcoming and casual, these two were both a bit more formal, likely a result of the density of deep pocketed collectors taking it rather seriously.

Down in Chelsea, the atmosphere was entirely different: the crowds were thick and full of life. My itinerary included the Dutch landscape show at Aperture (here), the Todd Hido/Nicolai Howalt show at Bruce Silverstein (here), and the Amy Stein show at Clamp Art (here). My first stop was Aperture, where the crowd waiting for the elevator filled the lobby and spilled out into the street; I opted for the stairs, which were just as packed. Up in the galleries, the crowd was clustered near the bar, with the viewing areas somewhat less crowded. This was not the case at Silverstein or Clamp; in these galleries, the viewers were jammed in like sardines, overflowing into every nook and cranny of available space.

In all three Chelsea venues, art viewing was a sweaty, bustling, bumping, free booze infused communal activity. The crowd was quite a bit younger overall; this time, I was likely on the older half of the age spectrum. While there were seemingly less collectors milling around, there was a fantastic energy to the entire neighborhood party, more a lively celebration of the return of art than anything else. The artists and gallery owners looked harried and exhausted, but happy with the huge turnout and running on adrenaline.

As a collector, what I took away from this whirlwind tour was a renewed set of questions about the split in the market between the “vintage” and “contemporary” worlds of photography. In many ways, each side could use a little more of what the other side has in abundance: the vintage photography market would benefit from an injection of the youthful energy of the contemporary market, while the contemporary photography market needs more attention from true collectors who will turn into real buyers, rather than those just out for free drinks and a good party. (By the way, we see this same exact split in our efforts on this site: posts about vintage/dead artists are usually well received by the collectors in the audience, but otherwise arrive with a thud for other readers; posts about contemporary work get shared and passed around on Facebook or Twitter, creating a flood of visitors who come by once and generally never return.) How we go about mixing the two worlds to their mutual benefit seems quite a bit more open for debate.

Overall, it was great to get out and see a bunch of fresh work and fresh faces. If these openings can be used as a barometer of confidence in the photography market, there’s a surprising amount of optimism in the air as we head into Autumn.

JTF (just the facts): A group show of three Japanese Conceptual artists: Koji Enokura, Hitoshi Nomura and Jiro Takamatsu, displayed in two adjoining gallery spaces. For Enokura, there are 11 black and white prints, ranging in size from 8×8 to 10×14, made between 1972 and 1974. For Nomura, there are 8 black and white images, all 20×24, made between 1968 and 1969, a black and white video of still frames made in 1973, and 4 larger color images (36×36, in editions of 5), made in 1979. For Takamatsu, there are 6 black and white images, ranging in size between 13×16 and 16×20, all made in 1973.

Comments/Context: While we don’t have a single photograph in our collection that could be grouped under the title of Conceptual Photography, I must admit that I am a secret admirer of this genre, as I enjoy being taken down the rabbit hole and shown events and places that go beyond the usual constraints of straight/documentary photography. But like anything, we can start at the top level with the umbrella of Photography, move down a rung to Conceptual Photography, and divide from there into decades, or geographies, and we can discover subcultures inside subcultures like nested dolls, with dozens of photographers who have had successful careers that are completely unknown to us. The three artists in this show are perfect reminders of how little we as collectors often know about many of the back roads and hidden neighborhoods of photography.

Comments/Context: While we don’t have a single photograph in our collection that could be grouped under the title of Conceptual Photography, I must admit that I am a secret admirer of this genre, as I enjoy being taken down the rabbit hole and shown events and places that go beyond the usual constraints of straight/documentary photography. But like anything, we can start at the top level with the umbrella of Photography, move down a rung to Conceptual Photography, and divide from there into decades, or geographies, and we can discover subcultures inside subcultures like nested dolls, with dozens of photographers who have had successful careers that are completely unknown to us. The three artists in this show are perfect reminders of how little we as collectors often know about many of the back roads and hidden neighborhoods of photography.

Koji Enokura’s images combine fragments of performances with the elegantly mundane. His works explore boundaries and contact points: between a hand and the floor, a body and a wave, a lead cube falling down a slope, or a puddle of water and the floor. Other images are simple glimpses of ordinary things: a truck tire or a rope around a tree. All of the works are quietly meditative. (Installation shot, at right top.)

The three Hitoshi Nomura’s projects on display are all connected by an underlying interest in the relationship between science and art. In one project, he constructed at 27-foot tall cardboard sculpture, and documented its eventual collapse under the weight of gravity and the effects of the weather. (Installation shot, at right.) In another, he used a film camera set at a very slow shutter speed, creating a set of flipping stills of his everyday life called The Ten Year Photobook or The Brownian Motion of Eyesight. In the last project, his camera was attached to a gyroscope to compensate for the rotation of the earth, creating blurred fields of color.

The three Hitoshi Nomura’s projects on display are all connected by an underlying interest in the relationship between science and art. In one project, he constructed at 27-foot tall cardboard sculpture, and documented its eventual collapse under the weight of gravity and the effects of the weather. (Installation shot, at right.) In another, he used a film camera set at a very slow shutter speed, creating a set of flipping stills of his everyday life called The Ten Year Photobook or The Brownian Motion of Eyesight. In the last project, his camera was attached to a gyroscope to compensate for the rotation of the earth, creating blurred fields of color.

Jiro Takamatsu’s prints echo the works of Ken Josephson, but with a different twist: in this case, the pictures of pictures are not used to make witty visual puns, but to consider the nature of memory. In each work, the artist’s family photo is obscured (by glare, or water, or shadow), leaving the stories incomplete, or subject to interpretation. I think there is an indirect connection or commonality of approach to the contemporary work of Bertien van Manen here as well. (Installation shot, at right.)

Jiro Takamatsu’s prints echo the works of Ken Josephson, but with a different twist: in this case, the pictures of pictures are not used to make witty visual puns, but to consider the nature of memory. In each work, the artist’s family photo is obscured (by glare, or water, or shadow), leaving the stories incomplete, or subject to interpretation. I think there is an indirect connection or commonality of approach to the contemporary work of Bertien van Manen here as well. (Installation shot, at right.)

None of these artists is or was a photographer in the traditional sense; they all use photography to expand their art making, but are known more broadly for their work in other media. As such, the works in this show are a little harder to characterize or relate to the larger span of photographic history; they fall in the cracks between the arts and force us to think in different channels. So while the discoveries to be found in this show are relatively understated, given the conceptual bent of this group, there are plenty of compelling ideas percolating around.

Collector’s POV: Individual images by Enokura are priced between $6500 and $8500. The group of 8 black and white images by Nomura is being sold as a set for $25000; the color images range in price between $30000 and $50000. The Takamatsu works are priced between $6000 and $9000.

Rating: * (one star) GOOD (rating system described here)

Transit Hub:

Enokura, Nomura, Takamatsu: Photographs 1968-1979

Through September 26th

McCaffrey Fine Art

23 East 67th Street

New York, NY 10065

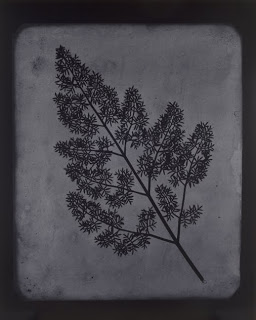

JTF (just the facts): Two toned gelatin silver prints by Hiroshi Sugimoto, from negatives by William Henry Fox Talbot. The prints are approximately 37×30 unframed, made in editions of 10. The works can be seen as an addition to the exhibition Hiroshi Sugimoto, Lightning Fields, opening today and running through October 31 at Fraenkel Gallery in San Francisco (here).

Comments/Context: A few weeks ago, our friends at the Fraenkel Gallery in San Francisco sent us a pair of image scans to take a look at. As any active collector knows, the sending of scans has become the de facto process for galleries around the world to communicate with their clients: the gallery staff considers which works might fit for a certain collector and then JPEGs of those works are emailed out. For some reason, the press has latched on to this practice as evidence of the irrational excesses of idiot collectors who are buying works “sight unseen”. The reality is that scans have made the art market much more liquid than it once was; it is now possible for dealers from all over the world to quickly and easily make their inventory available on a targeted basis, and with “no questions asked” and no cost to the collector return policies, buying from far flung locales is now relatively straightforward. But I digress.

The scans in my email inbox were of two new floral images by Hiroshi Sugimoto, and since we are floral collectors as well as fans of Sugimoto’s work, these were potentially a good match for us. I’ve attached them below: (Asplenium Halleri, Grande Chartreuse, 1821-Cardamine Pratensis, April 1839 and A Stem of Delicate Leaves of an Umbrellifer, circa 1843-1846, © Hiroshi Sugimoto, courtesy Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco)

Apparently, Sugimoto has been buying up some of Talbot’s earliest negatives out on the open market or from museums and has devised a way to make his own prints from them. As a reminder, original Talbot prints from the 1830s and 1840s are quite small, hardly ever larger than a single sheet of normal sized paper and nearly all of the florals are photograms. They are intimate and delicate in person, requiring the viewer to get up very close to see the intricate details of the flowers and leaves. They also come in a wide variety of colors, due to Talbot’s experiments with different chemicals, some of which are faded/dark and generally hard to see.

In the history of photography, the reprinting of an earlier photographer’s negatives by another artist has some strong precedents: Berenice Abbott printed Eugene Atget, Manuel Alvarez Bravo printed Tina Modotti, and Lee Friedlander printed EJ Bellocq (readers who can think of others, leave them in the comments). In each of these cases, the later photographer was attempting to the best of their ability to make prints that recreated the style/intention of the original photographer.

With these prints however, Sugimoto seems to be doing something altogether different. Rather than make faithful copy prints from the Talbot negatives, Sugimoto seems to be using them more like a musical score: the melody is the same, but the overall feel is open for interpretation and nuanced modification – he’s “playing” the negatives in his own style. As such, the new prints are much larger (37×30 will hold an entire wall), and in the top image, he has apparently combined two negatives into a single work. It may also be the case that the toning is different than the original prints, although we don’t have a “before and after” comparison that can be easily made.

Sugimoto is clearly interested in the workings of time, and has explored fossils and ancient art as precursors to photography via his own active collecting (his History of History exhibit at the Japan Society that brought together his photographs and selections from his personal collection of artifacts was one of the most memorable shows we’ve seen in the past decade). As such, this exploration of Talbot’s negatives doesn’t seem to me to be an exercise in grandstanding or hubris (which in the wrong hands it certainly could be), but more an archaeological questioning of how the history of the medium and its technical processes can inform the present. To use the musical analogy again, it’s like Glen Gould playing Bach; one master reconsidering another.

One thing is certain: from the scans, these are spectacular images. If there is a San Francisco based collector who plans to go to the Fraenkel show and wants to comment further on how the prints look in person, we’re all ears.

Collector’s POV: These Sugimoto prints are a direct hit in the center of our collecting target. The problem is that Sugimoto has become too well regarded/famous as an artist and his prices have been driven up too far; these recent prints are priced at $60000 each. So as I told the folks at the gallery, at this point, we’ll have to woefully admire/covet them from afar.

Transit Hub:

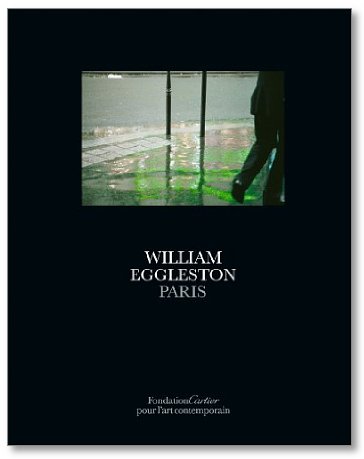

JTF (just the facts): Published in 2009 by Steidl (here) and the Fondation Cartier pour l’art contemporain (here). 184 pages, with 68 color photographs and 37 color drawings, divided into two intermixed sections. (Cover shot at right, via Photo Eye.)

JTF (just the facts): Published in 2009 by Steidl (here) and the Fondation Cartier pour l’art contemporain (here). 184 pages, with 68 color photographs and 37 color drawings, divided into two intermixed sections. (Cover shot at right, via Photo Eye.)

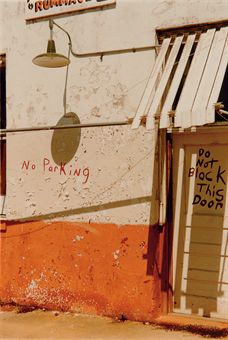

Comments/Context: Given the amount of adulation William Eggleston has received in recent years, it hardly seems to matter whether he ever makes another photograph; his influential place in the history of photography is already well solidified. And yet, here he is with a new body of work, continuing to refine his unique way of seeing.

Eggleston’s images of contemporary urban Paris (taken in the past three years) continue his evolution toward more fragmented and abstracted pictures. These works include less people and tell less complex narratives than his iconic images of the 1970s. There are more chaotic splinters and shards of frantic eye catching color; graffiti, commercial signage/posters, and neon lights all make repeated appearances. But each and every image still has at least one surprising element of color: a shiny red shoe, a pair of yellow shorts on a green park bench, a pink hat and a pink car together, or a reflected neon green glow captured in wet pavement.

Interleaved with the photographs are a number of densely patterned abstract drawings, reminiscent of mid career De Kooning (although less violent) or Kandinsky. At first glance, I found these splashes of manic expressive color distracting; there’s just too much stimulation to ignore them. But if we credit Eggleston’s genius as primarily that of a highly attuned eye for the relationships of color, then these drawings make more sense in the context of the photographs; they are simply a different manifestation of the same creative impulse, and the juxtapositions of the two show us themes and variations (in a musical sense) as they blast through his mind.

In general, the photographs in this body of work are uneven, and perhaps could have used a heavier hand in editing; overall, it’s not as strong top to bottom as some of his earlier projects. But if we strip away the bottom half and look only at the best of what’s found in this volume, it is clear that Eggleston still has an amazing eye for the overlooked, and can find unexpected hints of beauty almost anywhere.

Collector’s POV: William Eggleston is represented by Cheim and Read in New York (here). According to the gallery, the images in the show/book were artist’s proofs for exhibition only and there are no plans to edition them for sale. They are planning to have some of the drawings available when they open a show of new work by Eggleston in January 2010.

Transit Hub: