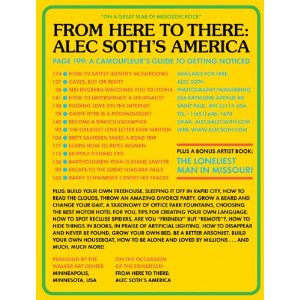

JTF (just the facts): Published in 2010 by Walker Art Center (here), in conjunction with an exhibition of the same name, on view now. 224 pages, with 237 color and black and white images. Includes essays by Siri Engberg, Geoff Dyer, Britt Salvesen, and Barry Schwabsky, a poem by August Kleinzahler, an interview with the artist conducted by Bartholomew Ryan, and a foreword by Olga Viso. Posts from the artist’s blog are also interspersed throughout the plates. The catalog includes a bibliography, exhibition history, and exhibition checklist. In the back, a 48-page artist’s book entitled The Loneliest Man in Missouri is held in a small pocket. (Cover shot at right, via Walker Art Center.)

JTF (just the facts): Published in 2010 by Walker Art Center (here), in conjunction with an exhibition of the same name, on view now. 224 pages, with 237 color and black and white images. Includes essays by Siri Engberg, Geoff Dyer, Britt Salvesen, and Barry Schwabsky, a poem by August Kleinzahler, an interview with the artist conducted by Bartholomew Ryan, and a foreword by Olga Viso. Posts from the artist’s blog are also interspersed throughout the plates. The catalog includes a bibliography, exhibition history, and exhibition checklist. In the back, a 48-page artist’s book entitled The Loneliest Man in Missouri is held in a small pocket. (Cover shot at right, via Walker Art Center.)

Comments/Context: Alec Soth’s first major museum retrospective is now on display at the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis, and for those of us who won’t likely get to see the show in person, this excellent catalog provides an unusually comprehensive view of his career to date. An artist’s first museum survey is usually an occasion for a carefully selected sampler of work from different projects, tied together with a handful of somber, scholarly essays, published in grand style to befit the seriousness of the moment. What I like best about Soth’s catalog is it’s overt subversiveness; while it of course contains plenty of images from the past 15 years and a handful of texts, it’s overall feel is unlike any other exhibition catalog I have ever encountered. The cover is both unpretentious and quirky. The essays wander all over the place, following exploratory tangents. Choice blog posts are interleaved, like little vignettes or thought bubbles. The obligatory artist interview is actually insightful and revealing. In short, the book is personal, real, and intelligently authentic, rather than packaged up in the normal trappings of haughty art world cool; it is joyfully nerdy and unabashedly eccentric.

The catalog covers the entire arc of his career to date, starting with his early black and white images from the 1990s, through Sleeping by the Mississippi, Niagara and The Last Days of W., to newer projects like Single Goth Seeks Same, Broken Manual, and The Loneliest Man in Missouri. Seeing all the work brought together and sequenced in rough chronological order, my biggest take away is that the pictures are a thorough and penetrating reflection of Soth’s day-to-day life as an artist. The cacophony of ideas that swirls around and between the photographs repeatedly comes back to Soth’s process: his wanderings, his road trips, his searching for lists of random things, his patience, his vulnerabilities, his discoveries, his chance encounters. He is the main character in this transparent novelistic story; the startling pictures are the inextricable end product of his purposeful excursions out into the world around him.

I think Soth’s success as an artist stems directly from his ability to cautiously open himself up to the frailties and anxieties of others, and to see in them some of the same seeking that lies within his own personality. Even in his earliest pictures, he catches the subtle awkwardness of strangers at a bar, a man and his poodle, a personal ad printed on a billboard in front of a snow covered yard – people looking for ways to connect, to share their passions, to be loved. Fast forward a decade, and he is still searching, seeing goth girls not as weirdos on the margin, but simply as people expressing their individuality and looking for like-minded souls who will treat them with respect and dignity.

Another way to get at this idea is to say that Soth’s pictures are always documenting emotions (even when they are obviously still lifes, landscapes, or architectural images). He has rejected all of the prevailing memes of recent contemporary photography: the cool conceptualism of the typology, the anything is art aesthetic, and the self-reflective art about art. He has instead turned inward, become introspective, and perhaps inadvertently tapped into the mood of current-day America. The more he does this, the better (and more nuanced) his pictures seem to get. The images from Broken Manual chronicle the lives of people trying to escape society, to live off the grid, in buses, caves and underbrush, with unruly beards and hand made tools, a hauntingly appropriate metaphor for those struggling with today’s economic hardships and feeling like they have nowhere to turn except to run away. Each one is just a piece of a very personal narrative, suggesting a more intricate story than meets the eye. Each also depicts a hidden landscape of emotional terrain, of reasons and rationales, of individualism, defensiveness, loneliness, fear, anger, and exhaustion. The little artist’s book tucked in the back of the catalog (The Loneliest Man in Missouri) is equally poignant: snapshots of men alone in cars, solitary men trudging through parking lots and along sidewalks, splashing lake fountains, and finally Ed getting a birthday song in his living room from Blaze (a stripper from Miss Kitty’s). The mini-theme unfolds with restraint, meandering here and there, and eventually punches you right in the gut. In both projects, Soth the artist and Soth the person are inextricably intertwined; he is both the narrator who is driving the plot forward and the one making the compositionally-spare photographs.

In the end, if you buy this book for your library, don’t just give it an idle flip of the plates and put it on the shelf for reference (although it will perform quite nicely in this mode as well). It merits a deep and thoughtful reading (yes, reading), and if you invest the time in this multi-layered, overlapped, not-yet-finished story, you’ll emerge with a surprisingly rich and personal view of one of contemporary photography’s most influential new leaders.

Collector’s POV: Alec Soth is represented by Gagosian Gallery in New York (here) and Weinstein Gallery in Minneapolis (here). Soth’s work has begun to appear in the secondary markets more consistently in recent years (a handful of lots each year), with prices ranging from roughly $4000 to $22000.

Transit Hub:

- Artist site (here)

- Little Brown Mushroom Books (here)

- Walker Art Center exhibition, 2010 (here, scroll down for dozens of links)

- Features: Star Tribune (here), Minnesota Public Radio (here)

- Review: Conscientious (here)

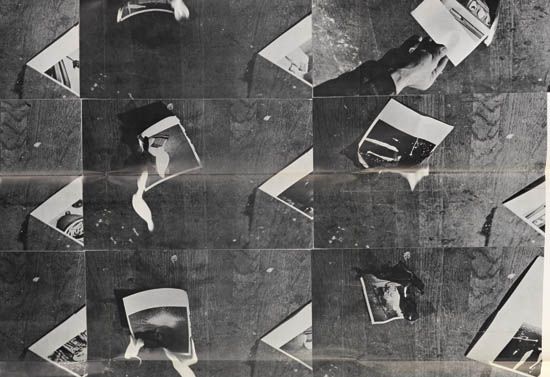

The difference here is that he has upended this personal retrospective by making each and every one of these pictures through the obstructed window of his rental car. Not content to make the same pictures twice, he has given himself a new challenge, with a new set of aesthetic mechanisms to break up his vision. The features of the cars provide him with a variety of complex compositional tools: square frames, borders, and dark slashing lines (from the car frame itself), sinuous curves (from the steering wheel and molded plastic dashboards), and picture in picture effects (from the reflections in the side mirrors, echoing a similar motif from the 1960s). Friedlander uses these structural devices to create additional disorienting layers of juxtapositions and perspectives that make the old subjects new again. (Lee Friedlander, Montana, 2008, at right.)

The difference here is that he has upended this personal retrospective by making each and every one of these pictures through the obstructed window of his rental car. Not content to make the same pictures twice, he has given himself a new challenge, with a new set of aesthetic mechanisms to break up his vision. The features of the cars provide him with a variety of complex compositional tools: square frames, borders, and dark slashing lines (from the car frame itself), sinuous curves (from the steering wheel and molded plastic dashboards), and picture in picture effects (from the reflections in the side mirrors, echoing a similar motif from the 1960s). Friedlander uses these structural devices to create additional disorienting layers of juxtapositions and perspectives that make the old subjects new again. (Lee Friedlander, Montana, 2008, at right.) Collector’s POV: Of course, none of the images in this museum show are for sale. See our review of the recent Friedlander gallery show at Mary Boone (here) for details about current price levels. As a reminder, Friedlander is represented by Janet Borden in New York (here) and Fraenkel Gallery in San Francisco (here). (Lee Friedlander, Alaska, 2007, at right, via the Whitney website.)

Collector’s POV: Of course, none of the images in this museum show are for sale. See our review of the recent Friedlander gallery show at Mary Boone (here) for details about current price levels. As a reminder, Friedlander is represented by Janet Borden in New York (here) and Fraenkel Gallery in San Francisco (here). (Lee Friedlander, Alaska, 2007, at right, via the Whitney website.)