JTF (just the facts): A group show gathering together works by 13 artists/collectives, variously framed/installed, on view in a series of rooms on the museum’s second floor. (Installation shots below.)

The following artists/collectives have been included in the show:

- Lake Verea (Francisca Rivero-Lake Cortina and Carla Verea Hernández): 3 chromogenic prints, 2019, each sized roughly 118×72 inches

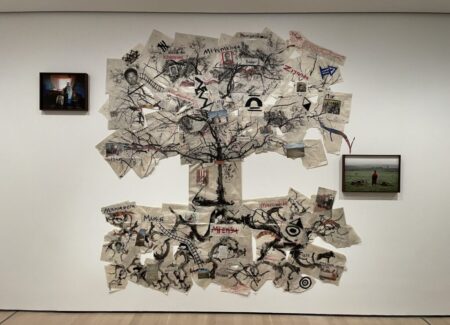

- Lindokuhle Sobekwa: 1 installation with photographs, Japanese kozo paper, gampi paper, colored pencil, oil pastel, acrylic paint, and polymer photogravure, 2025, site specific

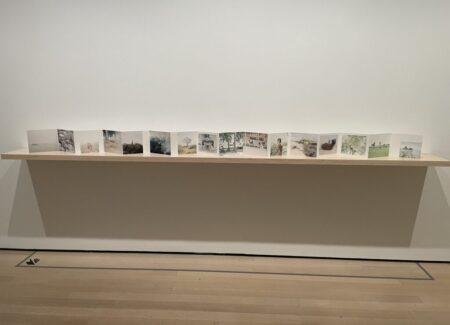

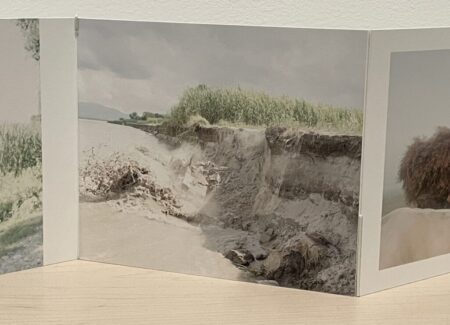

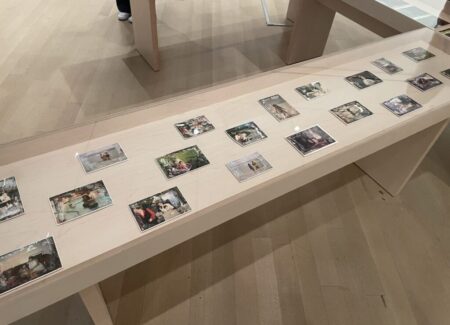

- Praslit Sthapit: 1 set of 13 inkjet prints mounted to board, 2021-2018, each sized 8×10 inches (or the reverse)

- Renee Royale: 4 inkjet prints, 2022, 2023, each sized 43×44 inches

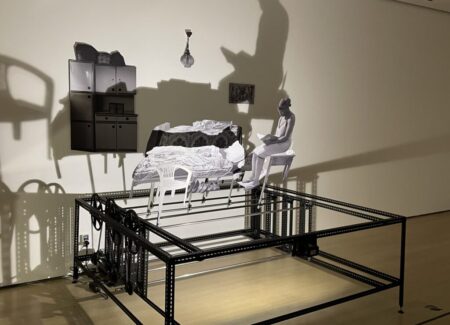

- Lebohang Kganye: 2 installations of inkjet prints, lit mechanical structures, 2022, each sized roughly 34x87x82 inches

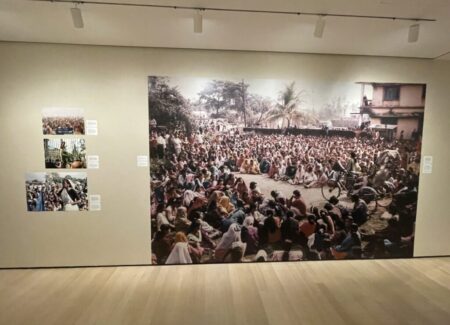

- Nepal Picture Library: 1 installation of digitally reproduced archival photographs, wallpaper, and text panels, 2025

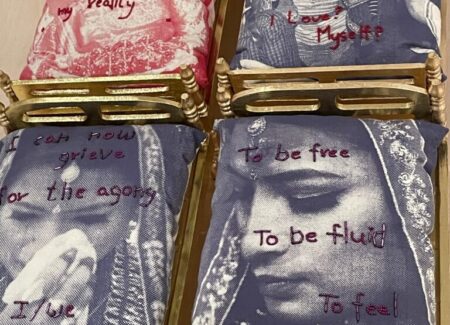

- Sheelasha Rajbhandari: 3 silkscreen prints on cotton, sheep wool thread embroideries, mixed cotton, 2020, each sized roughly 83×43 inches; 30 inkjet prints on linen, embroidery thread, metal thread, glass beads on 30 beds, wood, imitation gold leaf, 2023, each sized roughly 12x8x7 inches

- Tania Franco Klein: 12 inkjet prints, 2022, each sized roughly 30×40 inches

- Gabrielle Goliath: 11 inkjet prints, 2022, each sized roughly 35×35 inches

- L. Kasimu Harris: 5 inkjet prints, 2019, 2020, 2022, each sized 24×36 inches

- Gabrielle Garcia Steib: 1 installation with video (color, sound), photographic vinyl wallpaper, and 50 archival photographs, 2020-2025, site specific

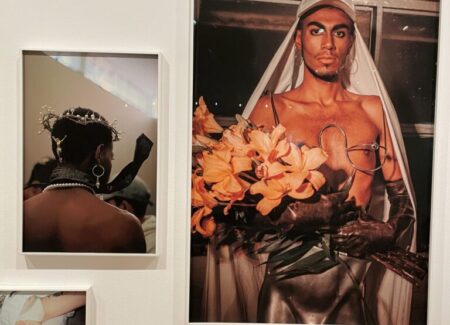

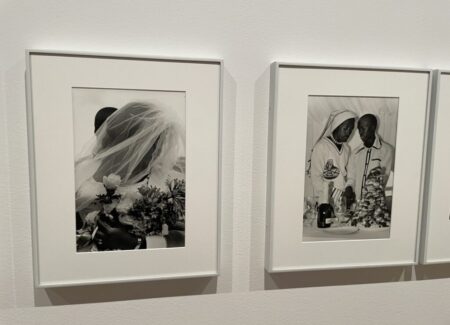

- Sabelo Mlangeni: 10 gelatin silver prints, 2003, 2004, 2011, 2012, 2014, 2016, 2018, 2020, sized roughly 10×14, 11×11, 14×10, 15×10, 15×11 inches

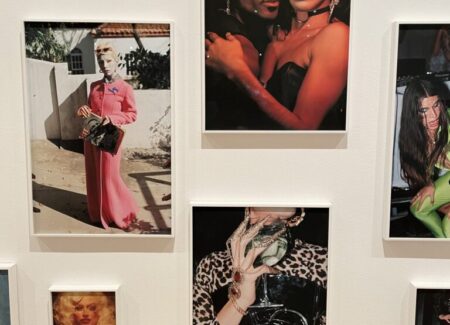

- Sandra Blow: 19 inkjet prints, 2017, 2018, 2019, 2020, sized roughly 8×11, 8×12, 11×8, 15×24, 18×24, 24×16, 43×29 inches

Comments/Context: Aside from various annual prizes, recurring art fairs, and summer group shows, there are surprisingly few exhibition traditions in the world of fine art photography, which makes the “New Photography” series at the Museum of Modern Art in New York a treasured exception. On a relatively annual basis since 1985, the photography curators at MoMA have selected a group of emerging, up-and-coming, or under known photographers and presented them as a snapshot of what was exciting, innovative, or simply new in the ever evolving medium at that moment, their choices often signaling the beginning of what would become influential art careers. Over the years, the curators have come and gone, but the central framework has stayed remarkably consistent, making the show a historical marker of sorts, especially with the benefit of hindsight.

This year’s 2025 version of “New Photography” marks our tenth visit to this special show. Up until 2013, “New Photography” was organized annually, with our reviews stepping back through the years: 2013 (reviewed here), 2012 (reviewed here), 2011 (reviewed here), 2010 (reviewed here), 2009 (reviewed here), and 2008 (reviewed here). In the past decade, the show has been a bit more intermittent (including a disruption during the pandemic), and often a bit larger and thematically broader than it was previously, as seen in 2023 (reviewed here), 2018 (reviewed here), and 2015 (reviewed here). Part of the enduring magic of this exhibit is that it mixes discovery, celebration, education, and forward thinking, with a backdrop of some of the world’s most esteemed curators going out on a proverbial limb to select artists worth paying attention to and trying to make longer term sense of the many trends taking place in the medium at any one time.

If there is a central theme to the 2025 iteration of “New Photography”, it is a proactive stance toward inclusion. Not only does the show inherently acknowledge that certain kinds of photographers have been marginalized or overlooked by places like MoMA in the past, it seeks to take as given that each photographer is finding his or her (or their) own “lines of belonging” (hence the subtitle of the show), which might take the form of families, histories, communities, and other forms of connection, and could also be defined by race, gender, sexuality, and geography, among other categorizations. This leads to an underlying curatorial framework that feels a little like a checklist, with each photographer included ticking off different boxes that define his or her (or their) unique collection of attributes that we then assume to inform their artistic practice. It’s a very identity-driven way of looking at what’s happening in contemporary photography.

A wandering walk through the galleries of this year’s “New Photography” offers two competing conclusions. On one hand, it is clear is that every project included has a distinct conceptual backbone, which tells us that this is a group of curators that is centered on the sophistication of ideas that sits underneath the picture making process; each selection can be understood intellectually, with an identifiable logic or reasoning for both how it was made, how it explores the nuances of personal identity, and where it fits in this exhibit. But on the other, there is very little photographic (particularly camera-based) innovation or unexpected risk taking to be found here, which is surprising. Either the works are reusing existing imagery (archival or otherwise) to make commentaries or installations or are following paths others have been down before but in slightly different locations or with somewhat alternate intentions/contexts. The compelling foundational ideas and rationales are all there, but when we look intently at the actual photographs on view, they’re often unexpectedly underwhelming – these artists are often making something visible that hasn’t been easily seen or noticed before, but the conceptual (and emotional) undercarriage of that process often feels more important than the actual picture making.

The top level filtering process that organizes this show is geographic, narrowing the potential photographic world down to work made by artists from four specific cities: Mexico City, Johannesburg, Kathmandu, and New Orleans. Obviously, these aren’t the usual artistic suspects of New York, Los Angeles, London, Paris, or even Tokyo, which immediately reorients our perspective; the curators have deliberately and intentionally looked elsewhere in search of what’s new and exciting in photography, and so by definition, what they find will similarly offer a corrective to a particular mode of white American or European-centric thinking. Each city is represented by three or four artists (or groups), offering an abbreviated survey of the photographic communities (and the ideas they are artistically investigating) in those places.

The Mexico City group (although the show is hung intermingled) is actually anchored by a project that isn’t rooted in geography; in fact, it asks us to strip that kind of thinking away. Tania Franco Klein’s “Subject Studies: Chapter 1” is one of the standouts of this show, mostly because it starts with a very rich conceptual idea, and then executes it with photographic flair. Franco Klein has created four setups – a bathroom, a diner table, the backseat of a car, and an office view through blinds – and has staged a variety of people in essentially the same pose in each setting. The result is a powerfully disrupting sense of how we perceive people – age, race, gender, and other identifiers are disorientingly multiplied, making us see inside the frameworks of our own stereotypes or assumptions. Sandra Blow’s photographs are conventionally unconventional, capturing the sparkly swagger of LGBTQ+ youth culture in Mexico City; her portraits are consistently well made and perhaps even particularly joyful in their personas and individualities, but they fit into a larger category of work (from around the world) that we have seen before. And Lake Verea (the artistic duo of Francisca Rivero-Lake Cortina and Carla Verea Hernández) also uses a conventional architectural photography format to isolate decorative details and embellishments with ties to Aztec, Mayan, and other Indigenous cultures, as incorporated into a broader Art Deco look; this is a straightforward idea that interrogates the complex overlapping histories of Mexico, but the photographs themselves are essentially documentary (with a distant echo of Eugène Atget’s French ironwork and door handles), even when printed extra large.

The Johannesburg group is similarly heavy on conceptual (and personal) resonance, but light on compelling photography. Lindokuhle Sobekwa’s wall-filling family tree installation is the strongest in the group, its expressive branches filled with headshots, snapshots, names, and obscure symbols; two framed images on the sides allude to Sobekwa’s very real talents as a photographer, but the installation feels more archival and investigative than newly seen. Lebohang Kganye’s contributions, in the form of two mechanical moving image sculptures, are even more dramatic and technically imaginative (particularly in the way individual images move up and down creating cast shadows), and their backstory (visualizing a science fiction tale of the return of the late Nelson Mandela) is certainly creative, but the novelty of their activated construction feels more durable than their visuals. And both the works of Sabelo Mlangeni and Gabrielle Goliath key in on visibility, with Mlangeni documenting the overlooked joy of various wedding festivities in South Africa (in different combinations of men and women) and Goliath grieving the loss of a childhood friend with stand-in portraits for each year since her killing. Again, the underlying ideas and intentions are sensitive and emotionally rich, but the photographs themselves aren’t entirely memorable, even when they touch on the fragility of those feelings.

When we turn to Kathmandu, Prasiit Sthapit’s project documenting the riverside settlement of Susta along the border of Nepal and India and its shifting location due to the eroding path of the river is conceptually one of the strongest projects in this show; there is so much thoughtful complexity in the idea of the climate-driven drift of a river forcing a community to straddle different border/national realities. And of the dozen or so prints included (on a small and difficult to see leporello), there are a handful of subtly seen color compositions, making Sthapit’s photographic potential the most tantalizing of the lesser known artists on view in this show. Sheelasha Rajbhandari’s works pack an emotional punch, particularly an installation of small golden beds with images of female faces and bodies printed on linen and hand embroidered with short testimonials and commentaries that consider the plight of married women in Nepal; their phrasing (like “my nightmare had become my reality”) brings a Jenny Holzer or Barbara Kruger text-driven bite to the overlooked burdens and taboos of traditional marriage, but the underlying photographic portraits (archival or other) are really only a small part of the larger artistic effort. And while the photographs included the photobook The Public Life of Women (drawn from the Nepal Picture Library) document a range of speakers, meetings, protests, and female activism across the decades, these anonymous images are resolutely documentary, showing us evidence of important and under known stories to be sure, but falling far outside the scope of what “New Photography” typically includes, even given the recent interest in recovering lost archival histories.

New Orleans is the final location in this globe trotting spin, with its layered cultural and racial legacies providing a conceptual foundation for various artistic approaches. L. Kasimu Harris’s images from his series “Vanishing Black Bars & Lounges” lead the way here, not only providing visibility to institutions and safe spaces for black residents that are slowly being displaced, but capturing them with a sophisticated eye for color and emotional nuance; this is a well-constructed, self-contained photographic project, executed with sensitivity. Renee Royale’s decayed images of polluted sites around Louisiana offer only hints of horizons and trees, their surfaces pushed toward the melting chemical abstraction of artists like Daisuke Yokota; her approach of burying her instant prints in dirt from the various locations follows a path trod by others in terms of incorporating local materials into her photographic process, the resulting enlarged images scarred and eroded by ecological destruction. And Gabrielle Garcia Steib’s installation of archival imagery and video footage takes aim at the migratory interconnection of Latin America with the southern US, linking Nicaragua, Mexico, and Louisiana into one sweep of family history, but her artistic edits and interventions aren’t nearly enough to transform the source material into something more resonant and durably original.

I’ll admit that this uneven show left me a bit frustrated and wrong-footed. I very much want to acknowledge the central idea of contemporary photography as a tool for visualization, where pictures of all sorts (made by the artist with a camera or gathered from other archival sources) are used to make lives, communities, and personal stories more visible – and I wholeheartedly agree that this is an important theme pulsating through the medium at this moment, and one that deserves to be explored more fully. And yet, aside from a few of the artists I’ve already singled out, I was largely underwhelmed by the photographic execution presented, with a handful of inclusions that felt check box perfunctory rather than particularly new, innovative, or revelatory. Of course, judging any artist by just a few images from any one single project is foolish, but I can’t say I came away entirely energized by what I saw in the 2025 version of “New Photography”. I don’t think that the correct conclusion is that a turn inward towards intimate and searching personal visualization inherently means a dumbing down of the photographic risk taking, but the evidence presented here isn’t as photographically astonishing and essential as I might have hoped.

Collector’s POV: Since this is a museum exhibit, there are of course no posted prices. Given the large number of artists included in the show, we will forego our usual discussion of individual gallery representation relationships and secondary market histories.