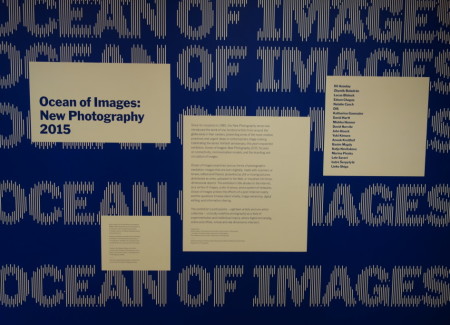

JTF (just the facts): A group show containing photographic works/videos from 19 artists/collectives, variously framed/unframed and matted/unmatted, and hung against white walls in five connected rooms on the third floor of the museum. Additional works can be found in the side stairwell lobby and the main entrance lobby. The exhibit was organized by Quentin Bajac, Lucy Gallun, and Roxana Marcoci, with the assistance of Kristen Gaylord.

The following photographers have been included in the show, with the number of works on view, their processes and dates as background:

- Ilit Azoulay: 1 set of 85 pigmented inkjet prints, 2014

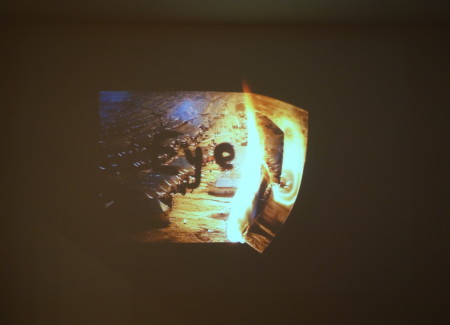

- Zbynek Baladran: 1 video (with color and sound), 13:29, 2014

- Lucas Blalock: 7 pigmented inkjet prints, 2013, 2014, 2015

- Edson Chagas: 5 stacks of offset lithographs on pallets, 2013

- Natalie Czech: 3 sets of chromogenic prints (4 with applied ink, 3, and 3), 2013

- DIS: 2 videos with color and sound, 2:46 and 2:44, 2015, 1 pigmented inkjet print on vinyl, 2015

- Katharina Gaenssler: 1 wall installation of photocopies and wallpaper paste, 2015

- David Hartt: 6 pigmented inkjet prints, 2013

- Mishka Henner: 1 video (black and white, no sound), 9:47, 2011, 1 artist’s book, 12 volumes, 2011

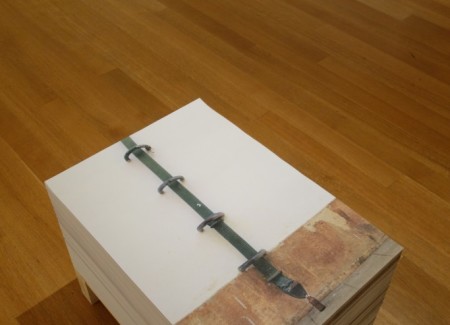

- David Horvitz: 1 artist’s book, 2015 (displayed as separate pages)

- John Houck: 5 pigmented inkjet prints, 2013, 2014, 2015

- Yuki Kimura: 9 gelatin silver prints with frames, iron, and plants, 2012

- Anouk Kruithof: 1 set of 99 pigmented inkjet prints and 5 pieces of colored glass, 2013

- Basim Magdy: 1 set of 30 chromogenic color prints from chemically altered slides on metallic paper, 2014

- Katja Novitskova: 2 digital prints on aluminum and cutout displays, 2015

- Marina Pinsky: 1 work made of UV-cured inkjet prints on aluminum and laminated glass, steel, epoxy, resin, and fiberglass, 2015

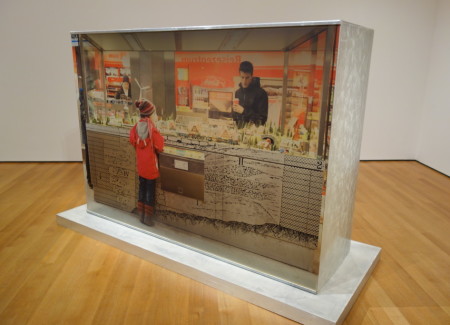

- Lele Saveri: 1 mixed-media installation

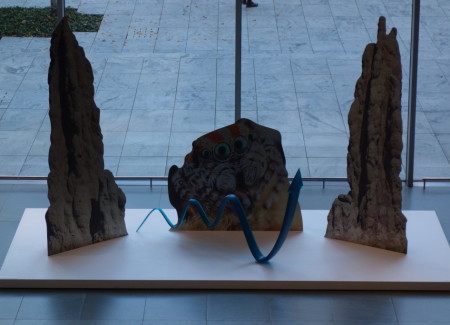

- Indre Serpytyte: 16 gelatin silver prints, 2009-2015, 8 wood carvings 2009-2014, 1 notebook, 2015

- Lieko Shiga: 11 chromogenic color prints, 2009-2012

(Installation shots below.)

Comments/Context: One of the exciting outcomes of Quentin Bajac’s early tenure as chief curator of photography at MoMA has been the conscious movement toward thoughtful inclusiveness he has pushed forward. While steps had already been taken during Peter Galassi’s term at the helm to mute and broaden the once tight omniscience of the John Szarkowski years, this process of opening the department up has continued with more momentum in the past few years. Placing the superlative excellence of Walker Evans in the middle of painting galleries was perhaps the first real earthquake, and Bajac’s inaugural studio-centric show was a smartly measured argument that the idea-driven work made in the confines of controlled space could be just as lastingly important as images taken in the streets or out in nature. This was soon followed by an impressively comprehensive reconsideration of between the wars Modernism to include more of the experimental German, Russian, and Eastern European work that had been forgotten or overlooked (via the Thomas Walther collection show), as well as smaller shows that brought forth Latin American/feminist themes (the Stern/Coppola show) and looked back at the beginnings of photography’ relationship with conceptual performance (the Shunk-Kender show). Seen from above, Bajac’s efforts to date have been marked by a methodical expansion of the medium’s previous boundaries and a dedication to proactively including those that had been previously marginalized – in short, he has systematically thrown open the doors to the tent of photography and welcomed in many who were previously stuck looking in from the outside.

Since 1985, the annual New Photography exhibits have been the primary way the museum has sought to engage with emerging photographic talent. In the past, these exhibits had been individual showcases of varying degrees, with as few as two or as many as a handful of photographers chosen to represent any given year, often without much thematic connection or visible relationship between the included artists. While this approach was effective in crisply singling out the artists the museum found worth highlighting (and as a result declaring an identifiable point of view), the shows often suffered from a lingering sense of randomness, the logic for and rationale behind the choices never made entirely explicit. Given all the other small but important changes Bajac has been making in the department, it should come as no surprise that he would shake up the New Photography series as well; it was clearly due for a fresh set of eyes. And as we might have predicted, he has opted once again for inclusiveness, expanding this new iteration of the show to some 19 artists/collectives from 14 different countries, taking into account variations in geography, gender, sexual orientation, race, and working process/style.

Ocean of Images arrives at a point when we are actively trying to come to terms with explosion of photography that has overtaken us, and it rightly reflects a cacophonous, multi-valent perspective – that’s indeed what’s happening right now, and the exhibit mimics that reality. But what’s intriguing is that when we opt for broad inclusiveness, we no longer enjoy the benefits of an intimate museum to viewer dialogue; this show is much more like a bustling cocktail party where multiple overlapping conversations are taking place at once than an emphatic top-down declaration of what’s exciting in the world of contemporary photography. Its glaring unevenness is inherent to its biennial-group show style, where a very loose theme provides a massive umbrella under which many divergent ideas and approaches can shelter. So while we’ve undeniably made gains in diversity and complexity with this exhibit, we’ve perhaps lost the laser-sharp focus of a museum making a reasoned argument about what’s durably important; this show doesn’t pretend that what it includes here will last, only that the larger ideas are representative of the divergent threads being followed at the moment. I didn’t like it when Charlotte Cotton employed a variant of this standing-on-the-sidelines approach in her recent book (reviewed here), and I am similarly wary of it here, however much it might feel like a mirror of the trends in the medium or of the world around us.

The only photographer who gets subtly special treatment in Ocean of Images is Lucas Blalock, whose deserving work is sprinkled around the show like a repeated connective refrain. We see his swirlingly digitally manipulated wood grain in the first room, followed by a pair of cleverly interwoven strawberries and candy wrappers a few rooms later, a canvas bag turned into the bottom of a shoe using wavy digital lines a bit further on, and then variants of the wood grain and shoe bottom again in the final room. This rhythmic hanging hits on several recurring themes: the ongoing waves of software-based manipulation, the now-common process of artistic iteration, versioning, and reuse, and the larger sense of photographic recirculation, where images appear repeatedly in slightly altered forms.

The main thrust of the recirculation concept is quickly picked up by several other artists. David Horvitz’ disassembled photobook chronicling the pathways of his head-in-hands “mood disorder” image uploaded to Wikipedia is the most literal examination of how a single picture can travel through the network and take on countless alternate meanings and associations; his artwork is a systematic document of the actual process of recirculation. Katja Novitskova offers a window into changing artistic thinking based on the availability of imagery – she reuses online natural history images of spiders and termites to construct larger-than-life sculptural objects. And three artists consider the mechanisms and trappings of recirculation itself, from the intrusive digital watermark on DIS’ seductive video, to the pallets of Edson Chagas’ free-for-the-taking posters and the guerilla subway station zine stand installation by Lele Saveri.

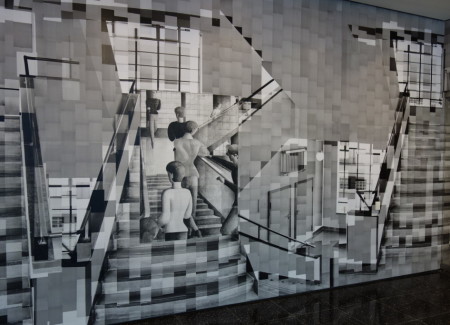

Recirculation then morphs slightly, and dives down into various archival investigations, leveraging the unearthed imagery as raw material and using it as a starting point for additional artistic journeys. Natalie Czech repurposes Pink Floyd album covers, an interview with Robert Longo, and catalog images by German industrial designer Dieter Rams, juxtaposing them with various poems and language fragments, realigning meaning based on the interplay of the text. Indre Serpytyte tracks down buildings in Lithuanian villages that were used for interrogation and torture during the Soviet years, creating visual and physical/sculptural stand-ins for the originals. Katharina Gaenssler wallpapers the back staircase of the museum in stuttering fragments of images of the original Bauhaus staircase in Dessau and paintings by Schlemmer and Lichtenstein in the MoMA collection. Yuki Kimura hangs rephotographs of her uncle’s 1960s images of a 19th century Japanese imperial villa on a sculptural iron framework amid green plants, turning them into a twisting installation. And David Hartt takes the archive idea literally, with photographs of the specific storage shelves of think tanks and lobbying firms (filled with policy whitepapers like “Dangerous Medicine” and “More With Less”), while Anouk Kruithof goes in the opposite direction, turning a found travel album into something deliberately anonymous, obscured, and open-ended.

A thin process-centric thread also wanders through the exhibit, though its connection to the overflowing spout of imagery is less clear. John Houck is represented by five illusionistic still lifes, where shadows are cast in competing directions, objects recur in multiple versions, and space is layered upon itself. Lieko Shiga’s post-tsunami views have been transformed by filters and manipulations, creating surreal red skies, ominous tire tracks, groping hands, and hungry crevasses. And Basim Magdy’s industrial and construction views are washed in candy-colored tints and chemical deteriorations. But these inclusions add little to our understanding of the vast “ocean” – the process imperative they represent (however exciting) seems bolted on to a largely unrelated central idea, the curatorial argument perhaps better served by photographers working with surveillance, Google Street View, machine-driven imagery, or other networked renderings.

The larger intellectual trap to be found lingering here is the mistaken conclusion that intriguing ideas necessarily lead to compelling photographs (or videos or whatever). While all of the included pieces on view here have some nugget of conceptual interest to make a viewer stop and think for a moment, less than half truly succeed as durably memorable artworks that engage us with some level of mystery, richness, and nuance; I had many moments of nodding in recognition at the ideas being presented, but then of feeling a bit deflated by the presence of the artworks themselves. Additionally, if we are measuring these works by their sophistication in engaging with the endless stream of available imagery that now confronts us (ostensibly the question posed by the exhibit), very few offer more than first level responses – it seems likely that many of these reactions will look particularly dated a decade down the line when we have become further immersed in an all-encompassing visual network. Put together, this exhibit leaves us with a mixed bag of work that only partially addresses the important issues raised by its organizing theme.

Admittedly, Bajac and his team are trying to do something that is very tricky; it’s not easy to find the right balance between authoritativeness and inclusiveness when surfing the bumpy leading edge of the medium. But this exhibit has swung too far toward the pole of friendly diversity, sacrificing too much of the curatorial editing and rigor that could have sharpened this selection down and clarified the artistic consequences derived from a surfeit of imagery; in this case, “more” has diluted the arguments, not broadened and reinforced them. If the MoMA photography curators are going to move to thematic approach for these New Photography exhibits (which may indeed be the best path forward), they need to crisply deliver on those structures rather than allowing them to become diffuse, overstuffed catch-alls where recent favorites/acquisitions are jammed in without fully connecting to the show’s theme. In the end, this exhibit is an admirable first step toward breathing new life into an exhibition series much in need of freshness, a well-meaning effort that will benefit from tighter execution next time.

Collector’s POV: Since this is a museum show, there are of course no posted prices. With so many artists/photographers included, our usual discussion of gallery relationships and secondary market histories becomes unmanageable, so we have omitted this portion of the analysis for this specific review.