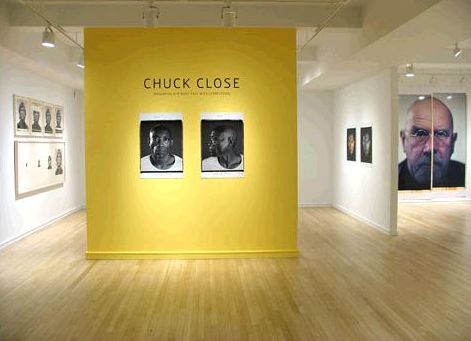

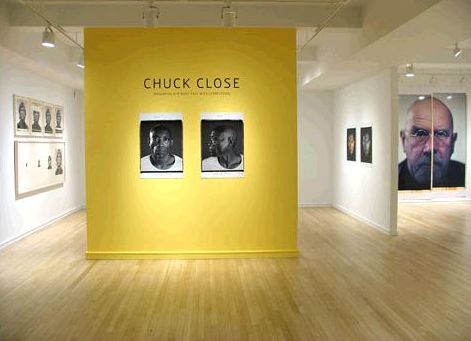

JTF (just the facts): A total of 17 works, many of which are diptychs or multi-part photographs, hung against white and yellow walls in the entry and two main gallery rooms. Most are framed in blond wood with no mat, with several pinned directly to the walls. The prints are a mixture of unique images and works made in editions of 7, 10, 15, and even 100, ranging from the mid-1960s to the present. (No photography is allowed at Pace/MacGill, so the installation shot at right is taken from their website.)

JTF (just the facts): A total of 17 works, many of which are diptychs or multi-part photographs, hung against white and yellow walls in the entry and two main gallery rooms. Most are framed in blond wood with no mat, with several pinned directly to the walls. The prints are a mixture of unique images and works made in editions of 7, 10, 15, and even 100, ranging from the mid-1960s to the present. (No photography is allowed at Pace/MacGill, so the installation shot at right is taken from their website.)

Comments/Context: I have had the good fortune to see Chuck Close make remarks at a few receptions and lectures in the past few years, and I am always surprised by both his crusty “seen-it-all” world weary demeanor and his repeated dismissals of photography as a medium; his comments have seemed a mixture of utter boredom with the discussion (and people) at hand and a desire to spark up a fire with some controversial zinger to keep the audience on its toes. In one room full of photography collectors and aficionados I was in, he started by saying the photography was easy to master, and ended by concluding that very few photographers ever found any original voice; perhaps both altogether true at some level, but certainly not what the crowd was expecting.

I suppose when you have been as successful as Close has for so many years, and with his fame surely generating incessant (and often annoying) demands on his time, it isn’t altogether unexpected that caring much what other people think seems to have drifted down toward the bottom of his concerns. What is puzzling however is that given his rich knowledge of photography in myriad forms that he has decided not to engage in many meaningful public dialogues about the nuances of the process choices he has made over the years.

This show would be a fine setting for such a discussion: there are black and white and color Polaroids (taken with his massive Polaroid cameras), monochrome and color pigment prints, gelatin silver prints, Iris prints, daguerreotypes and lithographs all on view. To consistently use such a wide range of approaches can only be evidence of an artist who has become an expert in the technical and visual details of each and every one of them (and many others not on display which were likely reviewed and discarded), and who then thoughtfully chooses which process fits his vision of any particular work.

In fact, the whole premise of this exhibit is to untie the knots of Close’s processes, to see the intermediate maquettes, working models, gridded proofs, and other photographic mock-ups he used, many of which became the basis for larger paintings. While a skeptic might call this group of works the recasting of in-process drafts as final artworks (complete with large swirling signatures for the status conscious), I saw it as a chance to see how Close had expanded the boundaries of his art by exploring all kinds of non-traditional photographic approaches that offered him different sets of tools to render his chosen subject matter.

While there are plenty of extra large, extreme closeups of various famous people (mostly artists) on view, I was most interested to see both a pair of nude torso daguerreotypes along with monochrome pigment prints made from daguerreotypes of Kate Moss (also nude); there were very real differences in scale, detail, tonality and overall viewer experience in these works, given their common heritage.

Overall, with some persistent looking, I found this exhibit to offer some subtleties that hadn’t been covered elsewhere. Close clearly continues to have a unique vision, and even if photography is a side show in his own mind, it can still be exciting for the rest of us.

Collector’s POV: The prices of the works in this show range all over the map, from $7500 for the lithograph to $175000 for the largest works; most range between $45000 and $85000. Close’s photographs have become more available in the secondary markets in recent years, finding buyers under $10000 on the low end up (works in large editions) toward $200000 at the high end. In general, we continue to hold Close’s work in high regard. Of late, we have spent some time considering a digital print of a Hydrangea daguerreotype Close made in recent years, as it would fit well with our collection of other florals and botanicals; we haven’t gotten to purchasing one yet, but perhaps we will at some point in the future.

Rating: ** (two stars) VERY GOOD (rating system described here)

Transit Hub:

- Hilton Kramer, NY Times 1981 (here)

- Chuck Close: Self-Portraits 1967–2005, SFMOMA (here)

- Lens Culture review of A Couple of Ways of Doing Something (here)

- Daguerreotypes (here)

Chuck Close, Maquettes and Multi-Part Work (1966-2009)

Through June 6th

Pace/MacGill Gallery

32 East 57th Street

New York, NY 10022

JTF (just the facts): A total of 71 photographs (it is often difficult to count “works” versus individual images, given multi-image installations), 1 sculpture, and 4 videos from a total of 20 different artists, on view in the main gallery area, which has been divided into four distinct spaces, plus the video room. All of the work comes from the 1990s and 2000s, and is variously framed/matted. (Installation shots at right.) The photographers included in the exhibit are:

JTF (just the facts): A total of 71 photographs (it is often difficult to count “works” versus individual images, given multi-image installations), 1 sculpture, and 4 videos from a total of 20 different artists, on view in the main gallery area, which has been divided into four distinct spaces, plus the video room. All of the work comes from the 1990s and 2000s, and is variously framed/matted. (Installation shots at right.) The photographers included in the exhibit are: I found the works by Charles Lindsay to be the most intriguing in the show (installation shot at right, middle). These carbon based images have a scientific feel, as though taken by an electron microscope or appropriated out of a scholarly article in Science or Nature. What I like about them is that they explore a more three dimensional type of abstraction, in contrast to most work in the show which is predicated on the flat two dimensionality of typical photography. The images have depth, and roundness, and edges, in addition to eye catching patterns.

I found the works by Charles Lindsay to be the most intriguing in the show (installation shot at right, middle). These carbon based images have a scientific feel, as though taken by an electron microscope or appropriated out of a scholarly article in Science or Nature. What I like about them is that they explore a more three dimensional type of abstraction, in contrast to most work in the show which is predicated on the flat two dimensionality of typical photography. The images have depth, and roundness, and edges, in addition to eye catching patterns. Ellen Carey’s “pulls” were also a memorable discovery. Using a 20×24 Polaroid camera, the artist makes abstract cones of color drawn from the photographic dyes. These works challenge the notion of what a photograph really is, and have affinities to a variety of color field and Minimalist painters.

Ellen Carey’s “pulls” were also a memorable discovery. Using a 20×24 Polaroid camera, the artist makes abstract cones of color drawn from the photographic dyes. These works challenge the notion of what a photograph really is, and have affinities to a variety of color field and Minimalist painters.