I have never met Carlos Cruz, but having pored over the catalog of his breathtaking single owner sale coming up at Christie’s next week, I have a deep respect and affinity for his underlying process as a collector. I have never been a particular convert to the spontaneous “buy what you love” school of photography collecting, so Cruz’ methodical, systematic, patient approach to building his collection resonates fully with my structured brain. While serendipity and lucky hunting are certainly part of the game of collecting, I could only nod my head in agreement with the description of Cruz’ activities in the front of the catalog: a rigorous study and pre-visualization of what he was looking for, a thoughtful logic and intellectual framework, a bounded period of time (roughly late 19th century to 1925), an emphasis on single, high quality examples, and a tireless adherence to this regimen. The fact that he was able to build this collection at a distance from the major art capitals (from Santiago, Chile) makes its breadth and quality all the more remarkable.

I have never met Carlos Cruz, but having pored over the catalog of his breathtaking single owner sale coming up at Christie’s next week, I have a deep respect and affinity for his underlying process as a collector. I have never been a particular convert to the spontaneous “buy what you love” school of photography collecting, so Cruz’ methodical, systematic, patient approach to building his collection resonates fully with my structured brain. While serendipity and lucky hunting are certainly part of the game of collecting, I could only nod my head in agreement with the description of Cruz’ activities in the front of the catalog: a rigorous study and pre-visualization of what he was looking for, a thoughtful logic and intellectual framework, a bounded period of time (roughly late 19th century to 1925), an emphasis on single, high quality examples, and a tireless adherence to this regimen. The fact that he was able to build this collection at a distance from the major art capitals (from Santiago, Chile) makes its breadth and quality all the more remarkable.

Nearly every single work in this catalog is a subtle wow moment of one kind or another; there is very little, if any, chaff in this bundle of exceptional Modernist/Futurist/Dada wheat. Perhaps what I like best is the sense of individuality in this collection, of not picking the best known or most highly regarded image by any of the masters in this parade, but of looking hard and long enough to uncover the gems that truly represent a photographer’s particular innovation or originality. There are great, unexpected choices everywhere: a great Rossler abstraction, an elegant Sudek broken dish, a tactile textured sheet by Modotti, the looming De Meyer chrysanthemums, the layered Funke bottle shadows, all extraordinary but less than obvious. Overall, there are a total of 71 lots of photography available in the sale, with a total High estimate of $7564000. I’m very much looking forward to the preview.

Here’s the statistical breakdown:

Here’s the statistical breakdown:

Total Low Lots (high estimate up to and including $10000): 2

Total Low Estimate (sum of high estimates of Low lots): $16000

Total Mid Lots (high estimate between $10000 and $50000): 32

Total Mid Estimate: $868000

Total High Lots (high estimate above $50000): 37

Total High Estimate: $6680000

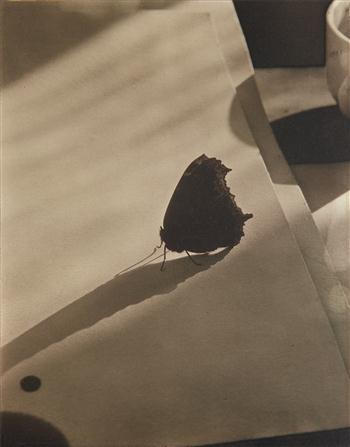

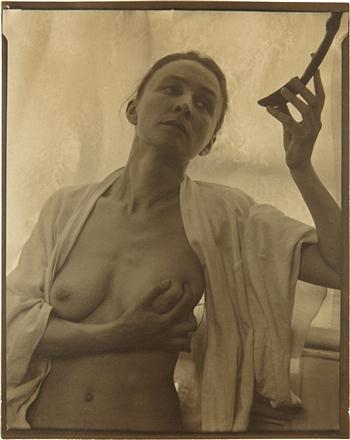

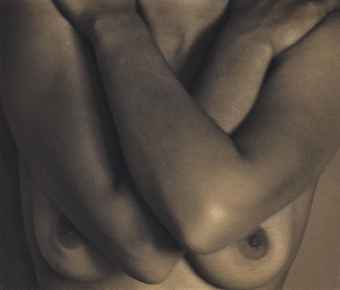

The top photography lot by High estimate is lot 7, Edward Weston, Nude, 1925, estimated at $400000-600000 (image at right, top, via Christie’s.)

Here’s the complete list of photographers represented by two or more lots in the sale (with the number of lots in parentheses):

Man Ray (4)

Edward Steichen (4)

Eugene Atget (2)

Anton Bruehl (2)

Etienne-Jules Marey (2)

Laszlo Moholy-Nagy (2)

Alfred Stieglitz (2)

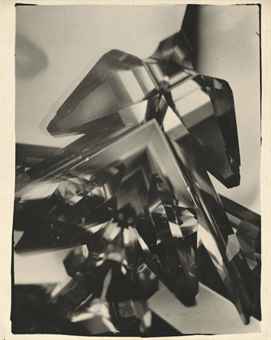

In an astonishing sale like this, it’s nearly impossible to single out just a few lots that are of particular interest. That said, here are two that had me shaking my head with amazement: lot 31, Alvin Langdon Coburn, Vortograph (The Eagle), 1917, estimated at $200000-300000 (image at right, middle, via Christie’s) and lot 24, Edward Steichen, Bricks (West 86th Street), New York, c1922, estimated at $200000-300000 (image at right, bottom, via Christie’s).

In an astonishing sale like this, it’s nearly impossible to single out just a few lots that are of particular interest. That said, here are two that had me shaking my head with amazement: lot 31, Alvin Langdon Coburn, Vortograph (The Eagle), 1917, estimated at $200000-300000 (image at right, middle, via Christie’s) and lot 24, Edward Steichen, Bricks (West 86th Street), New York, c1922, estimated at $200000-300000 (image at right, bottom, via Christie’s).

The complete lot by lot catalog can be found here.

The Delighted Eye: Modernist Masterworks from a Private Collection

April 4th

Christie’s

20 Rockefeller Plaza

New York, NY 10020