Part 1 of this two part post can be found here. Start there for background and a general explanation of the format of the summary. This portion of my notes covers the shorter area on the left of Pier 94 and all of Pier 92.

Lisson Gallery (here): Gerard Byrne (1), Cory Arcangel (2)

Max Wigram Gallery (here): Jose Dávila (1 set of 53, 1), Slater Bradley (1). Dávila is another artist playing with the properties of the cut photograph. In this work, he has taken pictures of famous sculpture from around the world and then excised the artworks, leaving white outlines and blobs which are surprisingly recognizable (entire set $65000).

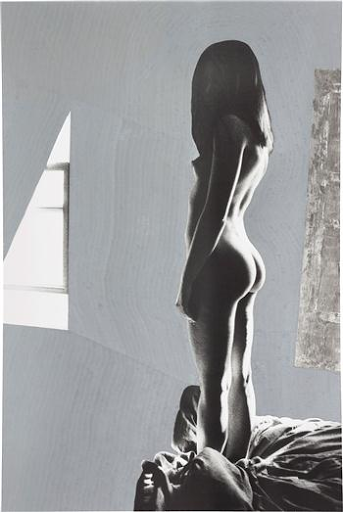

The surrounding area in the Bradley nude below is entirely covered in black marker, making a slightly striated and entirely opaque background ($40000).

i8 (here): Roni Horn (1 set 5), Orri Jonsson (3)

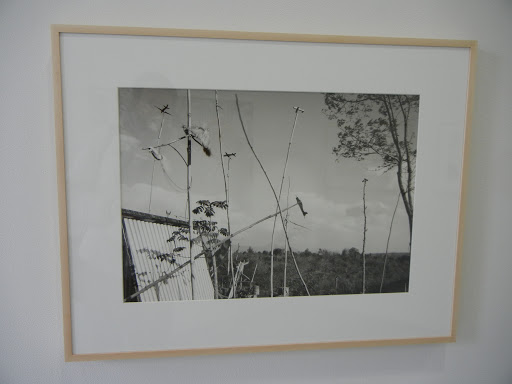

Galleri Bo Bjerggaard (here): Per Bak Jensen (1)

Loock Galerie (here): Holly Zausner (3 multi-image arrays)

Marlborough Chelsea (here): Rashaad Newsome (4 collages)

Yancey Richardson Gallery (here): Alex Prager (2), Zanele Muholi (5), Victoria Sambunaris (1), Sharon Core (1), Andrew Moore (1), Olivio Barbieri (2), Rachel Perry Welty (1)

Galleri Brandstrup (here): Ola Kolehmainen (2)

Paradise Row (here): Adam Bloomberg and Oliver Chanarin (1), Douglas White (1), Jane and Louise Wilson (1)

Rotwand Gallery (here): Klaus Lutz (5)

CLEARING (here): Ryan Foerster (9)

Rokeby Gallery (here): Matthew Sawyer (8)

Winkleman Gallery (here): Shane Hope (2). While most of the works in this booth were made using 3D printing, there were two quasi-photographic works on view: the one below (a digital print, $18000) and another, which was a holographic/lenticular print. The density of collaged digital imagery in this work is truly astounding, with layer upon layer of structural elements, exploded genomes, and other scientific models.

Victoria Miro (here): Isaac Julien (1), Idris Khan (1)

Sean Kelly Gallery (here): Frank Thiel (1), Alec Soth (2), Idris Khan (1), James Casebere (1). This is a new work by Casebere, with a falling table top house and a wildfire ($50000).

Galerie Rodolphe Janssen (here): Adam McEwen (2), Justin Liberman (1)

Galerie Nathalie Obadia (here): Andres Serrano (2), Youssef Nabil (2), Lorna Simpson (9)

Michael Kohn Gallery (here): Simmons & Burke (1)

Henrique Faria Fine Art (here): Alexandra Apostol (1)

Rena Bransten Gallery (here): Vik Muniz (2)

Other Criteria (here): Mat Collinshaw (3), Damien Hirst (1)

Parkett (here): Liu Xiaodong (1), Zoe Leonard (1), Yto Barrada (2), Tracey Emin (1)

Mike Karstens (here): Thomas Wrede (1), Gerhard Richter (2)

Mixografia (here): John Baldessari (1 set of 6)

Crown Point Press (here): Darren Almond (6)

Durham Press (here): Mickalene Thomas (1)

Bitforms Gallery (here): Rafael Lozano-Hemmer (2). These works were massive arrays of high definition scans of fingertips (taken from financial services employees), each rectangle its own individual set of whorls and lines ($37000).

Derek Eller Gallery (here): Thomas Barrow (1)

Galerie Forsblom (here): Ola Kolehmainen (1)

Galerie Daniel Templon (here): David LaChapelle (1), James Casebere (1)

Blain Southern (here): Wim Wenders (1)

Galerie Eva Presenhuber (here): Martin Boyece (1), Matias Faldbacken (2)

HackelBury Fine Art (here): William Klein (6), Mike & Doug Starn (3), Pascal Kern (4), Garry Fabian Miller (4), Bill Armstrong (3)

Wetterling Gallery (here): Mike & Doug Starn, Nathalia Edenmont (3), Pinar Yolaçan (2). I thought these works by Yolaçan were very smart. She’s taken fleshy nudes and covered the skin with some kind of textured lotion. With the heads cropped out and the bodies posed against colored backgrounds, they turn into stone fertility idols ($7500).

Galerie Michael Schultz (here): Andres Serrano (3), Vik Muniz (1)

Mireille Mosler Ltd. (here): Fischli/Weiss (1), Richard Prince (1). Pretty hard to beat this fabulous Fischli/Weiss shoe sculpture ($75000).

David Klein Gallery (here): Trisha Holt (2)

Alan Koppel Gallery (here): Garry Winogrand (2), Hiroshi Sugimoto (3), Patrick Faigenbaum (1)

Forum Gallery (here): Davis Cone (1)

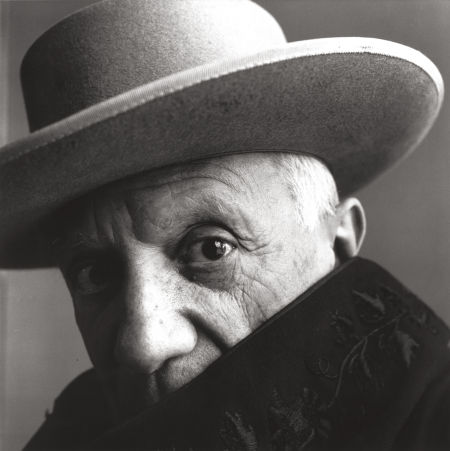

Robert Klein Gallery (here): Irving Penn (10), Bill Jacobsen (2), Francesca Woodman (4), Richard Avedon (1), Leonce Raphael Agbodjelou (3), Imogen Cunningham (1), Edward Weston (1), Alfred Stieglitz (1). Lots of vintage treasures in this booth, including a wall of bold Irving Penn fashion portraits. While there were other more famous Penn images on view, I enjoyed this one the most, with its tower of hair and its flared collar ($45000).

Fleisher/Ollman Gallery (here): Eugene Von Bruenchenhein (5)

Senior & Shopmaker Gallery (here): Robert Rauschenberg (1 collage of 4)

Marc Selwyn Fine Art (here): Rodney Graham (1), Irving Penn (1), Richard Misrach (1)

Chowaiki and Co. (here): Vik Muniz (2), Man Ray (1)

Galleria Repetto (here): Hiroshi Sugimoto (2)

Galerie Thomas (here): Marc Quinn (4)

Vivian Horan Fine Art (here): Almagul Menilbayeva (2)

JTF (just the facts): A total of 35 photographic works, variously framed and matted, and hung against white walls throughout the front room/entry, the main gallery space, and the smaller back room. The show mixes individual works by Nicolai Howalt (14) and Trine Søndergaard (10) and includes collaborations by the two artists together (11). The works span the period from 1997 to 2012. (Installation shots at right.)

Søndergaard