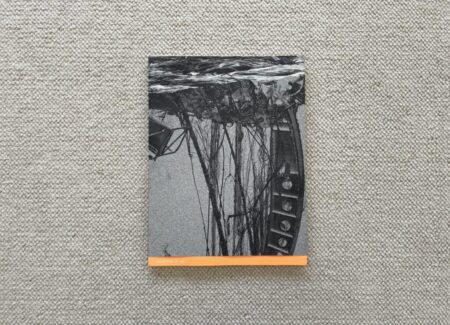

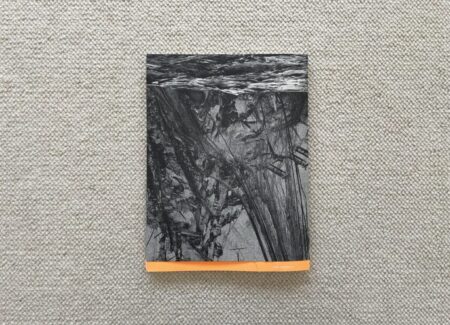

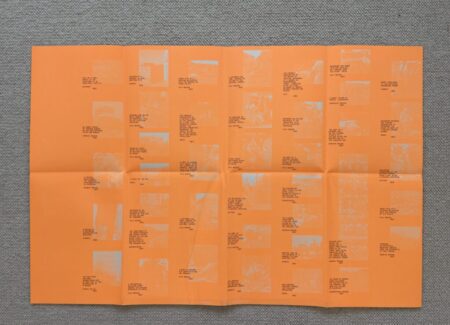

JTF (just the facts): Co-published in 2025 by XYZ Books (here) and FOTODOK (here). Softcover, 32×24 cm, with folded poster jacket, 96 pages, with 40 back-and-white reproductions (including one multi-panel image across several pages). Includes a poem by Joyelle McSweeney and an image list with captions (on the back of the unfolded poster). In an edition of 500 copies. Design by João Linneu and Fernanda Fajardo (Kakkalakki Studio). (Cover and spread shots below.)

Comments/Context: As the war in Ukraine grinds on, now entering its fifth year, the important task of photographing the land, the people, and the wider impacts of the invasion and conflict continue to evolve. Initially, an intense photojournalism effort was required to visually document what was actually happening on the ground in different areas of the country. And while that rapid documentary activity is still urgently needed to continue to thoughtfully tell the story of the ongoing war, the passing of time has also opened up some space for applying more deliberate and interpretive photographic approaches to areas where the fighting has receded.

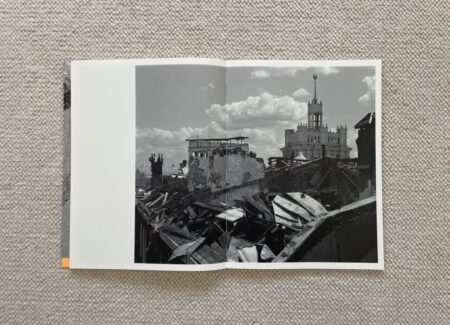

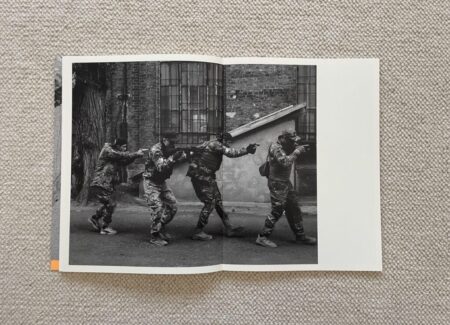

The title of Yana Kononova’s photobook Radiations of War is a particularly apt one, as it centers our attention on the aftermath of conflict and the seething desolation that now lingers in cities and towns across Ukraine – her pictures are a catalog of an indifferent war process that rolls on, rather than of discrete events or battles that are somehow “complete”. Starting in the spring of 2022 just after the initial invasion, Kononova’s travels have taken her to many war-ravaged locations around her home country, including the cities of Kyiv, Odesa, Kharkiv, Kupiansk, Kherson, Zaporizhzhia, and Okhtyrka, and the wider regions around and in-between those places. Using a medium format camera, she has patiently observed countless tragedies and aftereffects, applying a quietly lyrical gaze to the brutal evidence of death and destruction.

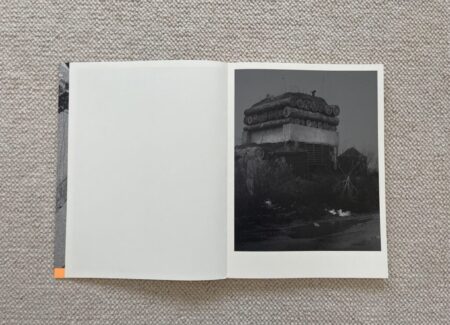

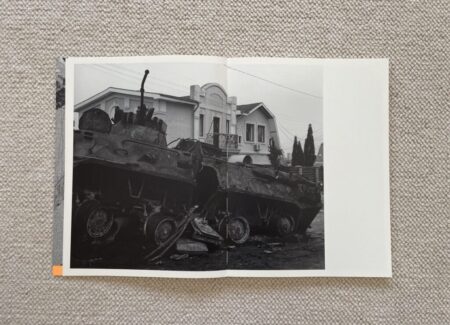

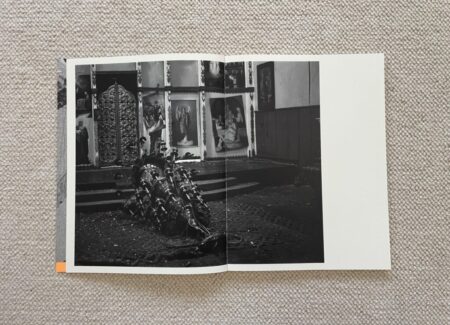

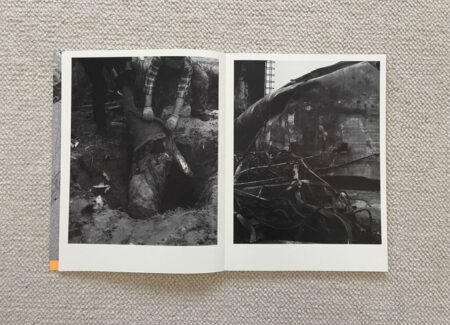

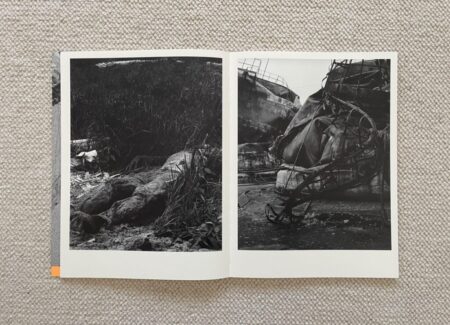

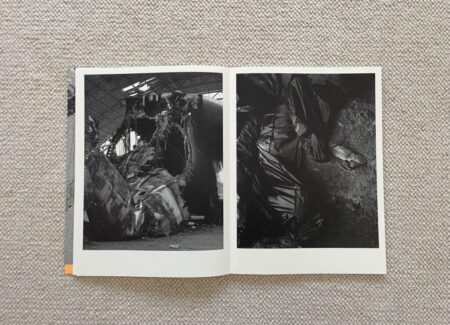

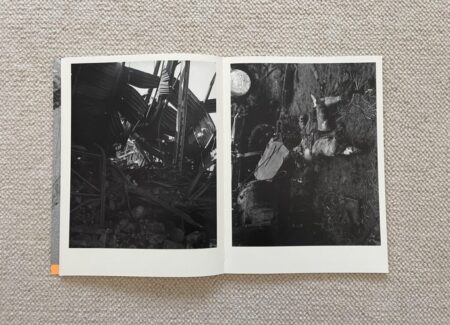

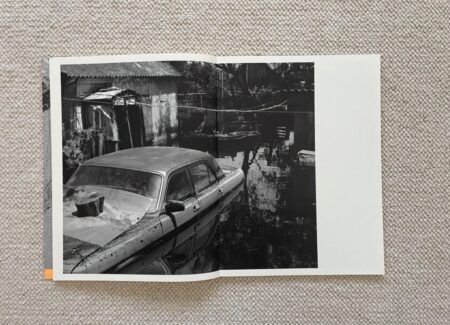

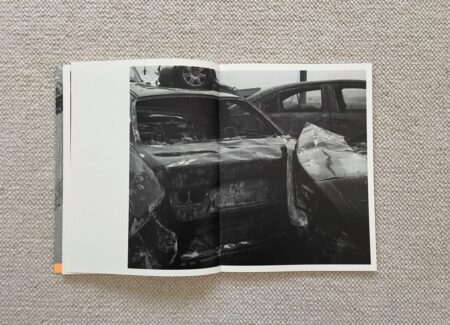

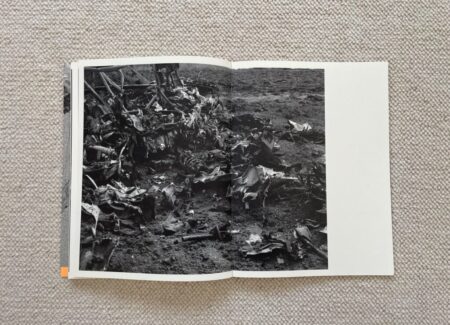

The descriptive captions to Kononova’s photographs (found on the inside of the folding jacket poster) offer a deadpan taxonomy of wartime violence: airstrike craters, burnt structures, destroyed cultural heritage sites, melted and deformed metal at industrial facilities, the wreckage of tanks and downed aircraft, the charred remains of abandoned vehicles, poisoned waterways, shelled churches, mass graves, and exhumed bodies wrapped in plastic sheeting. Such a list could hardly be more bleak, and Kononova doesn’t flinch from showing us these unadorned but disheartening truths. She appropriately requires us to witness these devastating realities, and to be present amid the silent ruins.

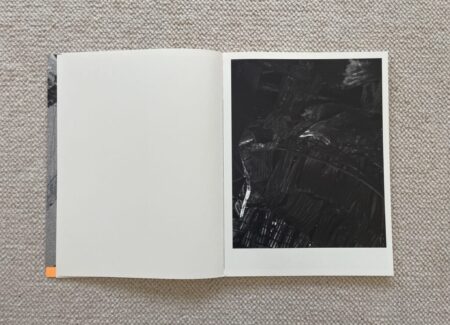

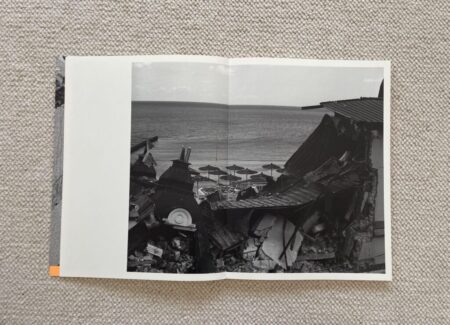

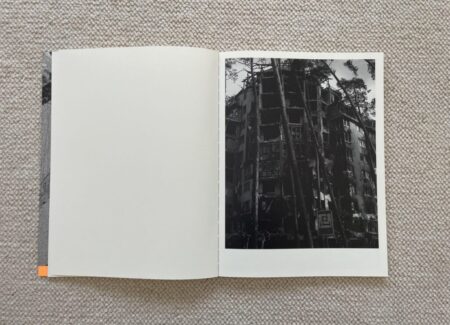

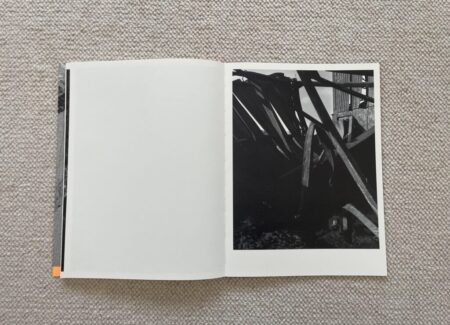

Kononova’s attentive approach strips away extraneous elements and leads to a surprising outcome – many of her images have a clear compositional grace, where subtleties of texture and tonality are used to amplify already evocative compositions. There is something unsettlingly poetic about her views of twisted metal, collapsed architecture, flooded debris, and scattered piles of rubble, in the way that photographs made after earthquakes, tsunamis, and other natural disasters often document artfully layered scenes of wreckage. But here of course, the slag is willfully man-made, making her scenes all the more visceral. Her surveys of shattered glass, crushed rock, scraps of metal, and piles of dirt can almost look abstract, that is until we notice a charred ribcage or a discarded body mixed in among the mess. And the tangled lines and forms of bombed out buildings or melted cars can have a similar Modernist elegance, especially when Kononova leans into the darker shadows, but this kind of emotional distancing only lasts for so long before we are brusquely brought back to the real world of bodies tied up in black bags, bodies left in the mud, bodies gunned down on the grass, and bodies pulled out of improvised holes.

Part of what makes many of Kononova’s photographs so poignant is the way she tells single frame stories. She pairs the burning roof of a house with the graceful drop of an overhead branch. She notices the fallen chandelier of an orthodox church. She uses the verticality of charred tree trunks to echo the skeleton of a bombed out apartment block. She tells the story of a destroyed dam via a view of dried up river beds. She fronts a beachside scene of water and thatched umbrellas with the devastation of a crumpled roofline. And she routinely transforms the recognizable into the unrecognizable, creating confusion and aching despair where there was once everyday order.

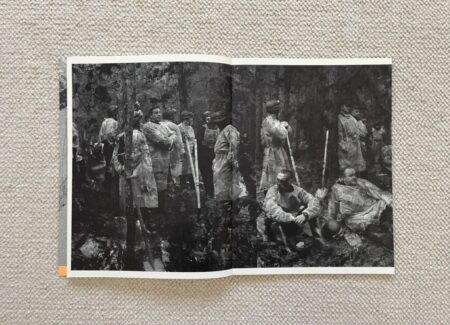

A careful look at a couple of Kononova’s large compositions reveals another layer of artistic interpretation going on, via some subtle image manipulation. Photographs of rescuers exhuming the bodies from graves found in the forest after the liberation of Kharkiv have been sequenced into a frieze-like composition that reaches across four spreads. In it, the men stand in plastic medical smocks, some wearing helmets and goggles and leaning on shovels, the wooded scenes connected end to end and then covered by chemical splatters and inversions, some appearing almost like hints of darkly encroaching waves, sickly decay, or faded memories. Kononova extends this aesthetic idea much further in the disorienting work that covers the book’s folded jacket – when unfolded, the image extends to eight panels of swirling wet horror. Up close, fragments of images appear to have been digitally stitched together, mixing waves with tangled piles of textural debris, creating a desolate feeling of sinking or drowning, a few vertical forms and dangling rope-like tendrils reaching all the way back to the grim moodiness of Theodore Gericault’s “The Raft of the Medusa”. In these pictures, Kononova has separated herself from a documentary requirement, and allowed herself to offer a more expressive and emotionally charged view of the events she’s witnessed.

Like Christian Rothe’s landscapes of the area surrounding the Buchenwald concentration camp (reviewed here), Kononova’s photographs of contemporary Ukraine wrestle with an unresolvable tension between beauty and ugliness. They go further than Oleksandr Glyadelov’s images of similar wartime scenes (reviewed here) by pushing the aesthetics of destruction to even higher heights of photographic refinement, which of course creates even more underlying friction and unease. In the end, the sophistication of Kononova’s image making constantly brushes up against the ruthless harshness of the war. Radiations of War is a jarringly confident display of photographic prowess, but one that memorably communicates the impossibly anguished dissonance of this historical moment.

Collector’s POV: Yana Kononova does not appear to have consistent gallery representation at this time. As a result, interested collectors should likely follow up directly with the artist via her website (linked in the sidebar.)