JTF (just the facts): A group show consisting of photographic works promised to the museum by Artur Walther and the Walther Family Foundation. The show includes images made by 22 artists/institutions, variously framed and matted, and hung against white walls in an exhibition space on the second floor of the museum. The show was organized by Jeff Rosenheim and Virginia McBride. (Installation shots below.)

The following works are included in the exhibition:

- François-Xavier Gbré: 2 chromogenic prints, 2012, 2014

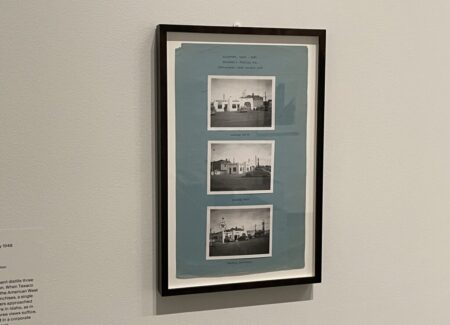

- Unknown maker: 1 set of 3 gelatin silver prints, 1948

- Bernd and Hilla Becher: 1 set of 15 gelatin silver prints, 1982-2001

- Société de Construction des Batignolles: 4 cyanotypes, 1901, 1902

- Günther Förg: 1 chromogenic print, 2001

- Thomas Ruff: 1 chromogenic print, 1983

- Mame-Diarra Niang: 1 inkjet print, 2014

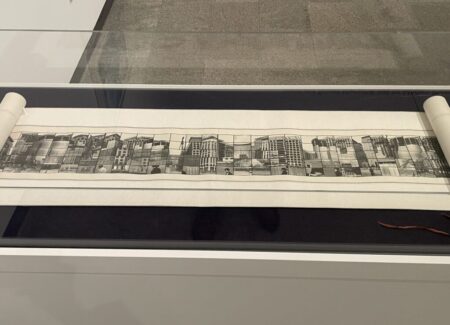

- Luo Yongjin: 2 gelatin silver prints, 1997; (vitrine) 1 inkjet print on scroll, 1998-2002

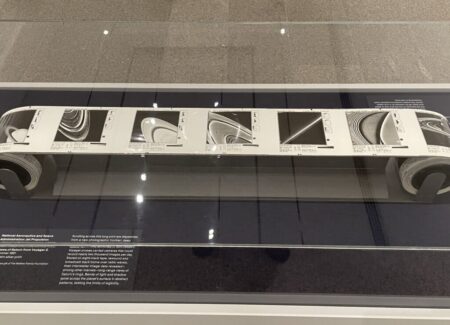

- (vitrine) NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory: 1 scroll of imagery, 1981

- Délio Jasse: 3 cyanotypes, 2014

- Oladélé Ajiboyé Bamgboyé: 1 set of 8 chromogenic prints, 1994

- Lisette Model: 1 gelatin silver print, c1939

- James Muriuki: 3 chromogenic prints, 2005

- Yto Barrada: 1 chromogenic print, 2006

- Mimi Cherono Ng’ok: 1 inkjet print, 2008/2018

- Kohei Yoshiyuki: 3 gelatin silver prints, 1971

- Mikhael Subotzky/Patrick Waterhouse: 1 12-channel digital slideshow, 2008-2011

- Santu Mofokeng: 2 gelatin silver prints, 1991, 1996

- Weng Fen: 1 chromogenic print, 2001

- Aida Silvestri: 3 images with stitched thread, text panels, 2013

- Nobuyoshi Araki: 6 gelatin silver prints, 1992, 1993

- (vitrine) selection of 9 catalogs published by the Walther Collection

Comments/Context: For many active photography collectors, acquiring a handful or two of carefully chosen works each year might be a plausible pace of collecting, over a lifetime leading to a collection perhaps measuring in a few hundred images. But in amongst the collecting minnows lurk a few bulkier whales, who collect in an entirely different manner and at an entirely different scale. These are collectors that buy not only acknowledged icons but entire bodies of work, who commission projects and portfolios, who unearth and acquire overlooked artists’ estates, and who build museum-rivaling collections quickly, supported by an array of display spaces, dedicated curators, and scholarly publications. During the first two decades of the 21st century, Artur Walther was this kind of voracious collector, and this appetizer-sized exhibit of a vanishingly tiny portion of his collection can’t hope to tell the story of his exhaustive collecting activities in much detail.

Walther’s collecting eye first landed on German masters like August Sander and Bernd and Hilla Becher, but it soon wandered much further afield. Walther is perhaps best known for shining a very bright light on some under appreciated photographic geographies, being among the first big time collectors to dive deeply into African photography, then Chinese and Japanese photography, and later vernacular imagery. He built a museum-quality space in Neu-Ulm, Germany, and second smaller location here in Chelsea, where he hosted an ongoing rotation of meticulously curated exhibitions, most accompanied by catalogs published by Steidl. During the period between 2012 and 2020, I visited the Walther Collection space here in New York often (here), as it was generally the only place in the city to see African or Chinese photography in any depth or detail. At last tally, Walther’s collection totaled some 6500 works of photography and video, so to attempt to winnow that complexity down to 40 representative works feels like a fool’s errand; the good news is that a more comprehensive survey of the collection is scheduled for 2028.

In terms of organization, View Finding is very much a one-of-each, tips-of-the-waves survey, with works from different points in Walther’s collecting history thoroughly mixed together. A 15-piece grain elevator typology by the Bechers is a decent place to start, as it roots us in Walther’s early interest in German aesthetics, while also signaling his ongoing exploration of the built environment, structured image-making, and multi-image sets and series. Other works by Thomas Ruff (an early interior) and Günther Förg (an extra large print with a steep Bauhaus-like vantage point) amplify these ordered ideas and provide an intellectual foundation on which Walther then continued to build.

When Walther turns his attention to African photography, some of these same themes emerge, as seen in architectural works by François-Xavier Gbré, Mame-Diarra Niang, and Délio Jasse. He then branches out to sequential investigations of identity (by Oladélé Ajiboyé Bamgboyé and Aida Silvestri), while picking off standout single images from Yto Barrada, Santu Mofokeng, and Mimi Cherono Ng’ok. And as an extension of Mikhael Subotzky and Patrick Waterhouse’s landmark project “Ponte City” (originally reviewed here, in 2014, in photobook form), Walther commissioned a 12-channel video work, documenting views from various floors of the infamous Johannesburg apartment complex. These works highlight some important ideas and themes in the collection and introduce a few new names to the Met, but in no way even begin to capture the depth and richness of the collection’s African photography holdings.

Our trip through Walther’s interest in contemporary Chinese and Japanese photography is even more fleeting. Modular architectural images by Luo Yongjin, including a continuous scroll of gridded urban views of Beijing, continue the global investigation of construction, which Walther then balances with more provocatively intimate Japanese projects, including Kohei Yoshiyuki’s nocturnal park encounters and Nobuyoshi Araki’s nudes and still lifes filled with desire and loneliness. Additional works by Weng Fen and James Muriuki fill out the abbreviated Asian lineup, but again, the show only offers hints of the collection’s deep study of Chinese contemporary photography in particular.

In more recent years, Walther applied similar logics and frameworks to vernacular discoveries, seeing structured thinking and sequential image making in a range of unlikely photographic places. Here we see anonymous circulating views of a 1940s era gas station in Idaho, in-process construction images of a viaduct in France, and automated images of Saturn from the Voyager 2 space probe, each a resonant example of Walther’s thinking process. The three projects also allude to adjacent modes of analyzing photography, exploring time-based series as well as alternative processes (like the cyanotypes and NASA artifacts.)

To my eye, reducing Walther’s expansive collection down to such a small sampler is almost criminal, but I know the Met’s intentions are good. Instead, perhaps we should think of this show as an interactive save-the-date announcement, giving us a tantalizing peek at the bigger exhibition coming down the road. Few 21st century collectors have essentially single-handedly redirected attention with such ferocity and intellectual rigor, so mark your calendars for 2028, when the real meat of the Walther collection will be visible.

Collector’s POV: Since this is a museum exhibition, there are of course no posted prices, and given the large number of artists included in the show, we will forego our usual discussion of individual gallery representation relationships and secondary market histories.