JTF (just the facts): 22 artists represented by one work each (although some contain multiple images or a series), displayed in the Joyce and Robert Menschel Hall, a large white box of a room with a high ceiling. Here’s a list of the artists in the show (alphabetically):

Vito Acconci

William Anastasi

Lutz Bacher

Sarah Charlesworth

Moyra Davey

Liz Deschenes

Roe Ethridge

Kota Ezawa

Janice Guy

Sherrie Levine

Robert Mapplethorpe

Allen McCollum

Richard Prince

Josephine Pryde

Thomas Ruff

Allen Ruppersberg

Karin Sander

Hiroshi Sugimoto

Andy Warhol

James Welling

Christopher Williams

Mark Wyse

Comments/Context: The new contemporary photography gallery is probably the only place (save the special exhibits areas) in the hallowed halls of the Met where some real risk taking in exhibit making can take place. The art in this room hasn’t necessarily weathered the trials of decades or centuries, and any one work may or may not have yet risen to the top as best of breed for a certain style or time period. It’s a place where fresh ideas can be shown, providing interesting contrasts to what’s on view elsewhere in museum.

This exhibit takes on the challenge of making sense of the entire sweep of photography since the 1960s. Some of the themes it touches on include:

- Appropriation/rephotography

- The idea of truth in photography

- Conceptual photography

- Photography as a ubiquitous mass medium

- Photographic advertising

- New and old photographic processes

This is a small gallery remember, and therefore a relatively limited place in which to tell the stories of all these individual movements/concepts coherently. As a result, I’m sorry to say that this exhibit had a random “dressed in the dark” feel for me. I felt I had to engage each work and play the guessing game of which theme this particular image was trying to represent – “why is this here” for each and every picture or series of images. With some effort, these puzzles can be deciphered and the audience can see the thought process behind the exhibit; it just takes some  work, and I’m guessing that 80% of the fly-by viewers who stroll through these galleries on their way to someplace else will leave mystified. While the mix of established artists and unknowns is a good thing, there was just so much going on that the juxtapositions of different works didn’t seem to make much sense (I bet this will be the first and only time that a Sugimoto portrait and a Welling flower will hang next to each other; see the Welling image at right, 012 Flowers, 2006). Given the size of this space, any one of the themes mentioned above could fill this room with an interesting and representative array of work to tell its particular story more thoroughly. So while risks are good, perhaps some tighter focus is required.

work, and I’m guessing that 80% of the fly-by viewers who stroll through these galleries on their way to someplace else will leave mystified. While the mix of established artists and unknowns is a good thing, there was just so much going on that the juxtapositions of different works didn’t seem to make much sense (I bet this will be the first and only time that a Sugimoto portrait and a Welling flower will hang next to each other; see the Welling image at right, 012 Flowers, 2006). Given the size of this space, any one of the themes mentioned above could fill this room with an interesting and representative array of work to tell its particular story more thoroughly. So while risks are good, perhaps some tighter focus is required.

As an aside, there are two entrances to this room, that are nearly equally likely for someone to come through. This exhibit was arranged generally chronologically, so if you came in through the far doors are worked back (as I did), it seems even more of a grab bag, until you get to the other end, where the historical context is more obvious. I think the lesson here is that this room does not lend itself well to a linear narrative, and shows need to be monolithic in this space.

Collector’s POV: For our particular collection, there were really only a couple of works that would fit well. The first is the flower image I referenced above by James Welling. This is a large image, hearkening back to various hand crafted processes of the past, but fully rooted in the present and with a strong point of view. If we had a wall big enough, I could imagine one of these in our collection.

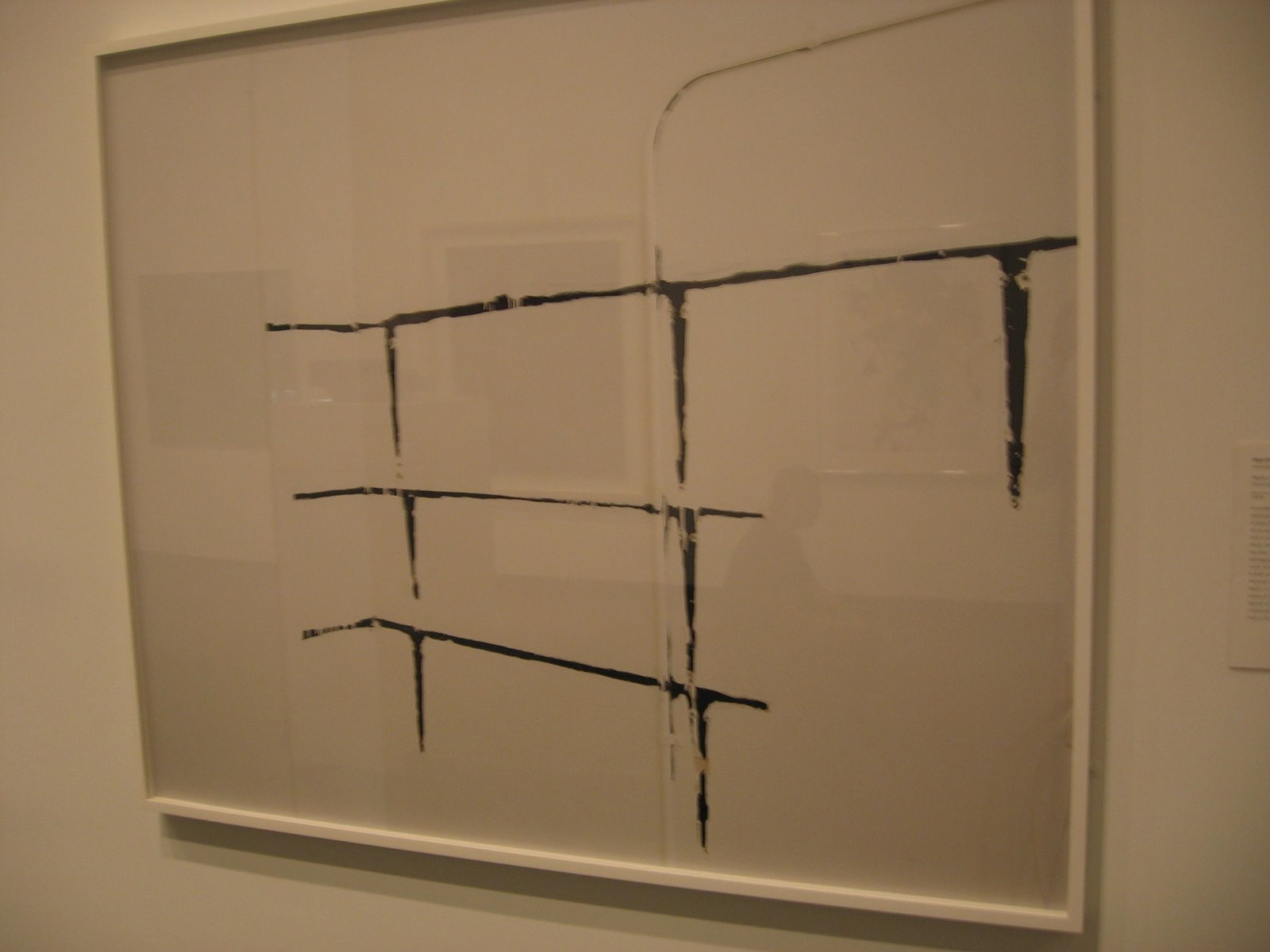

A second is Mark Wyse’s Mark of Indifference #1 (Shelf) from 2006 (see image at right). This artist was previously unknown to me, but I liked the simplicity of the vision.

While not a fit for us, I think the Sugimoto wax figure portraits in general (there is one of Fidel Castro in this show) are both thought provoking and spectacular. My guess is that they will end up being truly signature pieces from this era.

Rating: * (1 star) GOOD (rating system defined here)

Photography on Photography: Reflections on the Medium since 1960

Through October 19th

Metropolitan Museum of Art

1000 Fifth Avenue

New York, NY 10028