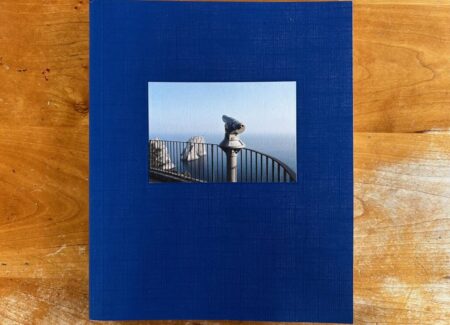

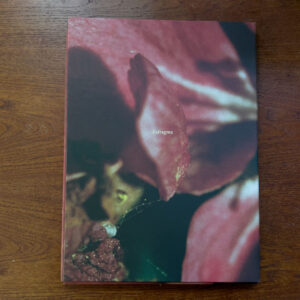

JTF (just the facts): Published in 2024 by MACK Books (here): OTA-bound buckram flexicover with tipped-in cover image, 21.5 x 25 cm, 184 pages, with 117 color photographs by the artist and 37 supplementary images in the accompanying texts. Includes essays by Tobia Bezzola, James Lingwood, and Maria Antonella Pelizzari. Design by Morgan Crowcroft-Brown. (Cover and spread shots below.)

Comments/Context: Luigi Ghirri’s photo career was short and sweet. Born in Scandiano, Italy, in 1943, he spent his twenties as a land surveyor before switching rather abruptly to—a tangentially related discipline?—photography in 1972. Although he couldn’t know it at the time, Ghirri would live only twenty years longer before dying of a heart attack in 1992. He was extremely productive in his last two decades, compiling reams of images, projects, and writings. Plenty for future historians and curators to dig through, as it turned out. Ghirri’s archive has been widely circulated, sifted, and argued over since his passing.

That’s the situation today. But during his lifetime, Ghirri’s reputation was geographically constrained. For photo connoisseurs in Italy or certain European art centers, Ghirri was a prominent figure. But for those in the rest of the world, he was not well known. Unfortunately for American photo fans, those benighted realms included the United States. Ghirri’s reputation lagged stateside for his entire life, notwithstanding a 1980 exhibition at Light Gallery in New York. It wasn’t until 2008 that he began to gain broader posthumous traction, sparked by the retrospective monograph It’s Beautiful Here Isn’t It, and its accompanying exhibition at Aperture Gallery in New York (reviewed here).

That book and show ignited a flurry of interest in Ghirri which continues to the present. The revival has been supercharged by the arc of history, as Ghirri’s old photographs pose questions about picture making and image-saturated globalism which have gained increased pertinence in the digital age. When contrasted with the fashion of his epoch— littered with post-f/64 schmaltz and darkroom abstractions—Ghirri’s approach feels prescient indeed. As a result he’s has become one of those steadfast creators—in good company with Eugène Atget, Mike Disfarmer, Vivian Maier, and others—who generates more interest after death than while alive.

MACK books has been at the forefront of the crate digging, starting with the re-publication of Ghirri’s classic monograph Kodachrome in 2012 (reviewed in exhibition form here), then continuing tentatively with a collection of Ghirri postcards and a book of his essays in 2016. From there the rush was on. Colazione sull’Erba followed in 2019, Puglia in 2022, and Italia In Miniature in 2024, all sandwiched around the retrospective survey The Map And The Territory in 2019. With the exception of this sweeping tome, each of these monographs bit off a small slice of the Ghirri oeuvre for curation and consideration.

MACK’s monograph Viaggi is the latest addition to the Ghirri catalog. It is published in conjunction with an exhibition at the Museo d’arts della Svizzeria italiana in Lugano, Switzerland, which closed in late January. The show and book are both are curated by James Lingwood, who also edited The Map And The Territory. Developing himself into a Ghirri expert, he realized that “the journey, as idea and as image, resonates throughout his work.” A book/show on the theme seemed only natural. For Viaggi, he culled photos from various projects spanning Ghirri’s entire career, 1970 through 1991. As its name implies (viaggi is translated as trips in English), they are unified loosely around the theme of travel.

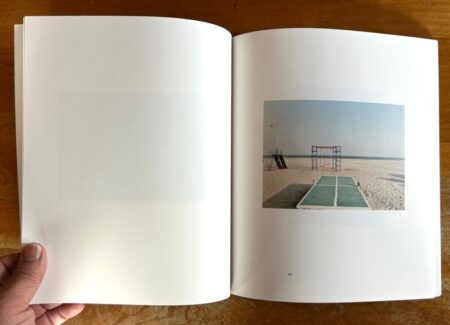

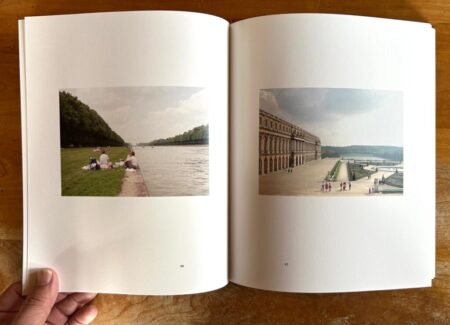

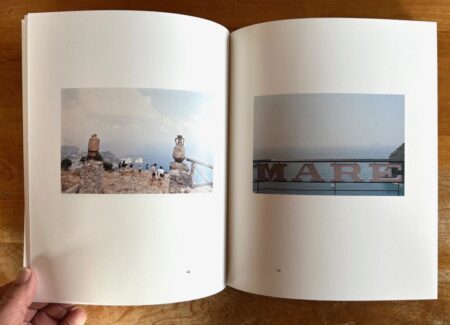

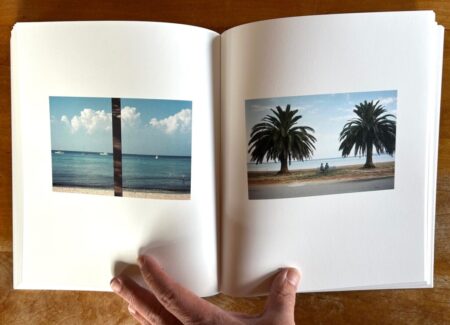

Book title notwithstanding, Ghirri did not take many distant viaggi, and he could not be considered a globetrotter. Instead he generally occupied himself within a few hundred miles of his home in Modena. Still, Italy being Italy, he found plenty to photograph within that radius. Viaggi flits between Italian destinations like Rome, Venice, Florence, Naples, Capri, and Rimini. Ghirri also visited natural attractions such as Corsica, the Dolomites, and Swiss Alps, and various Italian lakes. On occasion he branched further afield to European locales like Salzburg, Versailles, and Paris. Even if he wasn’t a jet setter, he got around. For a straight color photographer whose images were generated by unplanned encounters, these journeys held natural appeal. They promised new subjects, new experiences, and new worldviews.

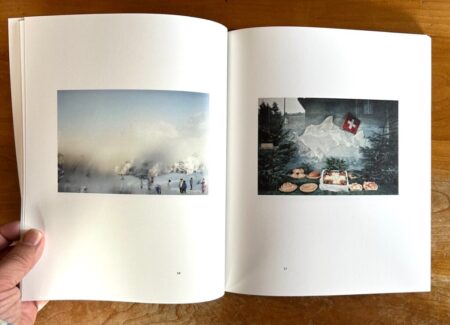

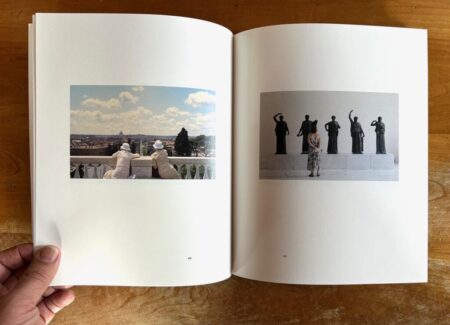

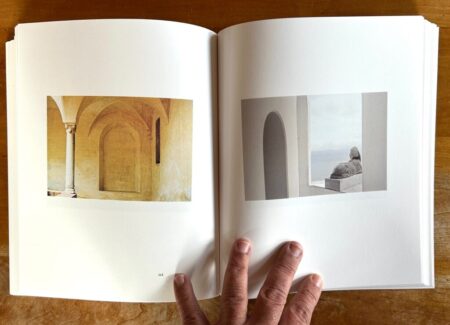

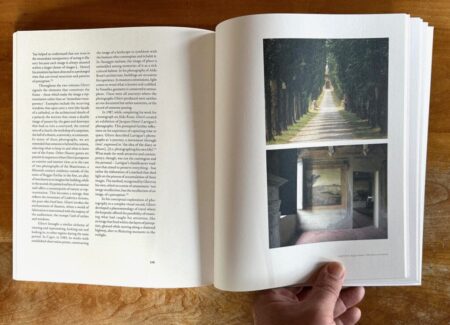

The hunt for raw material was one impetus for travel. But since Ghirri approached the world as a surrealist trickster, his photographs assumed a meta-level twist. As evidenced in Viaggi, his junkets were less concerned with particular places than with the act of tourism itself. The book’s sequence winds through one amazing vista after another, especially in the initial sections. Ghirri visits snow capped peaks, deep blue lakes, alpine meadows, famous paintings, landmarks, and more. It’s the late 20th century version of the Grand Tour. Every destination is stunning. Each one must be seen to be believed.

Visiting these famous photo ops, Ghirri’s attention is elsewhere. He is less interested in spectacles than spectators. Many of his photos are foregrounded with gawking couples and crowds. Random strangers turn away from Ghirri to soak up the scenery, inadvertently becoming his subject matter. As we the readers consider these Rückenfigur backsides, our POV transfers to them, and with it any majestic potential. Awe is supplanted with irony, and the Grand Tour is turned inside out. All as Ghirri intended. What’s the purpose of hiking another grand peak, he might ask, when “every time we visit places we carry with us the burden of what has already been experienced and already seen”?

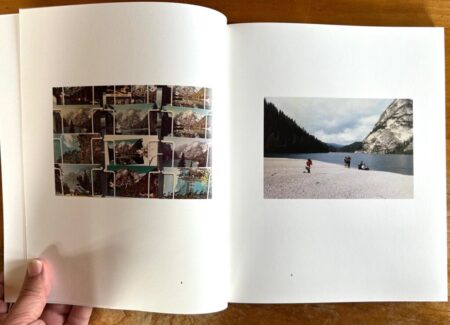

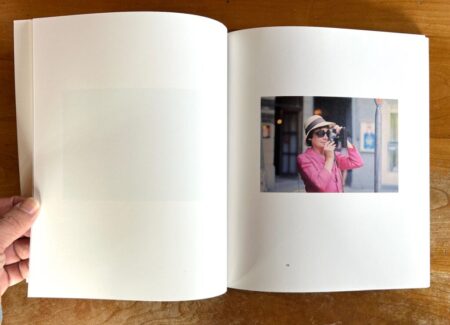

Send tourists on vacation anywhere, and there will of course be pictures. Indeed, photographs are a routine method of marking territory and codifying lived experience. For Ghirri this behavior was an endless source of fascination, not just because he was a photographer, but because he was interested in the nature of images, and in their motivation and construction. Viaggi includes several candid photos of snapshotting travelers in action, fingers cocked, capturing this or that memorable (or forgettable?) site. One shows a distant woman photographing her family near Lago de Brais. In another photo Ghirri captures a Parisian aiming her film camera somewhere out of frame. This is a rare close up, and one of the few frontal figures in the book. A stand in for himself perhaps? Another revealing close up shows Ghirri behind his own camera, selfied in a Rimini mirror. Studying the resort scene chopped in thirds behind his reflection, we might wonder about his quote: “I always have a point of escape in my images.”

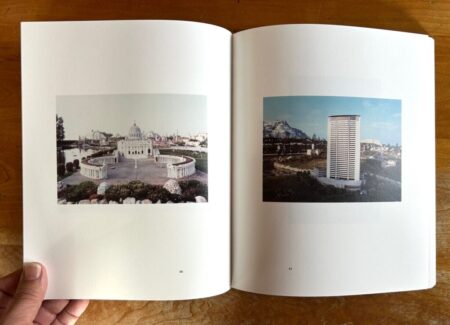

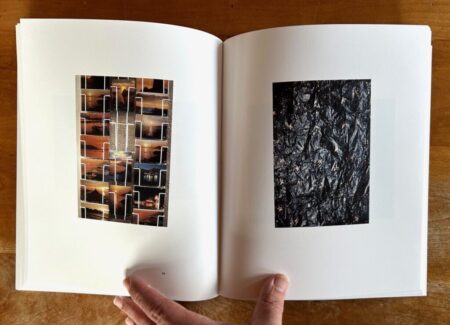

As evidenced in this self portrait, Ghirri’s fascination with picture-making extended to his own frames. How does one put a photo together? Where are the breaking points? Viaggi sees him continually toying with technique, composition, perspective, and trompe l’oeil effects, all leavened with surrealist zeal. In some photos, mountains are mountains. In others, they are faux-peaks found in diorama models. The same conflations applied to cities and streets, sometimes real, sometimes scale replicas. A vista might be clean, or reversed in a mirror. Ghirri was fond of posters, ads, signs, and other image-heavy subjects, reappropriating them alongside unmediated reality. His eyes operated as one big 2D blender. (For more thoughts on how Ghirri constructed images, see our 2020 review of “The Idea Of Building”.)

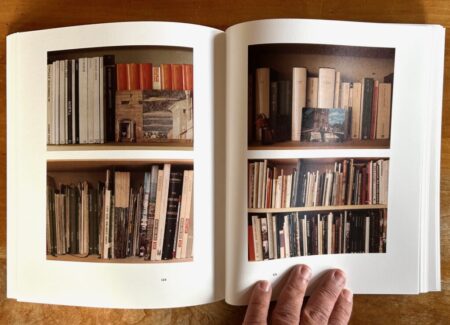

Throw in Ghirri’s natural bent toward layered ambiguities—railings cleaving formal shapes, a beach billboard creating a preformed photo frame—and the visual games are on. “Reality is being transformed into a colossal photograph,” he wrote, “and the photomontage already exists. It’s called the real world.” Considering his era, the futurism of that statement is almost eerie. But trick-weary readers needn’t fret. For those wanting a dose of straight WYSIWYG imagery, Viaggi includes a sampling of found postcards from Ghirri’s massive personal collection.

How does Viaggi fit into the Ghirri catalog? It takes a big swing, and it’s generally successful. The photos may not be entirely new—several have included before in previous Ghirri books—but the concept is fresh. Using the lens of travel, it galvanizes Ghirri’s images around exoticism, artifice, and surrealism, among his core photographic concerns. The quality of image making is consistently strong, and some photos are exceptional.

With a timespan and project this broad, there will naturally be a few hiccups knitting everything together, and that’s true with Viaggi. The images range widely in style and location, and the edit feels sprawling and disjointed at times. Quiet beach scenes, crowded viewpoints, oddly cropped maps, classical architecture. It might be too much to ask for all to flow seamlessly. But that small quibble is overshadowed by the general strength of Ghirri’s vision. Now that he’s passed on, it’s up to the current generation to sift, edit, and reweave his photographs in new ways, much the way that he jigsawed real world elements into carefully constructed frames and series. Viaggi is a step in that direction, and a worthwhile trip through Ghirri’s world.

Collector’s POV: The estate of Luigi Ghirri is represented by Matthew Marks Gallery in New York (here). Ghirri’s prints have only been intermittently available in the secondary markets in recent years, with prices ranging from roughly $1000 to $55000.

Good review and a fair one Blake. I spent some time with Adele and her husband recently at the Ghirri home. I love the book but I see your points. The best Mack book on Ghirri by far was “Puglia” . That book was great!