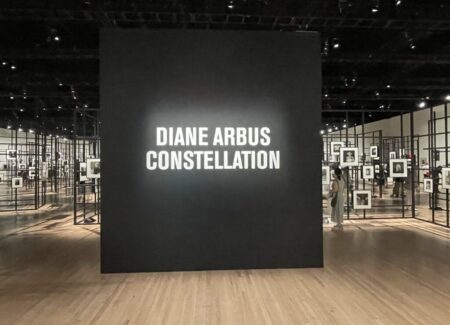

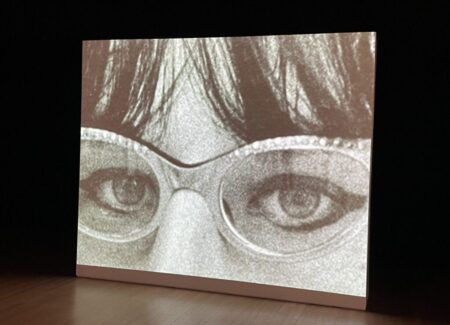

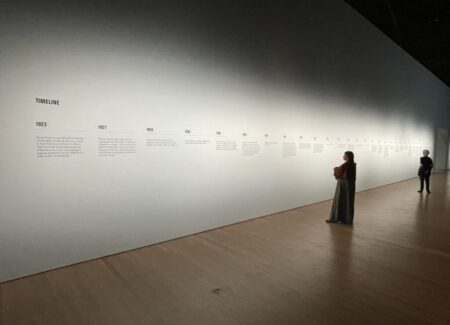

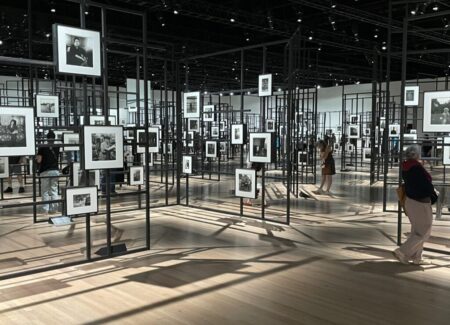

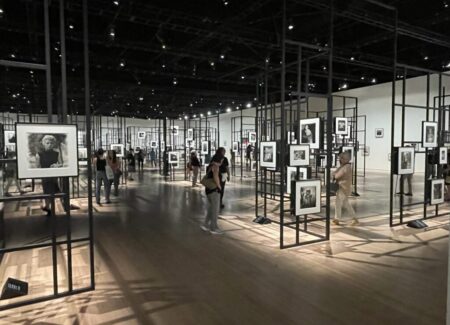

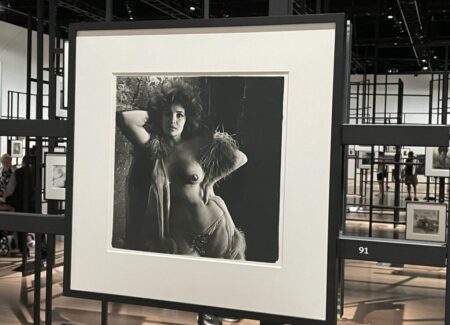

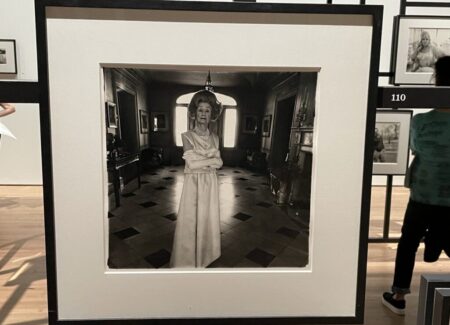

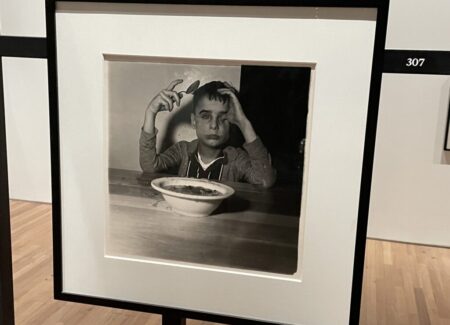

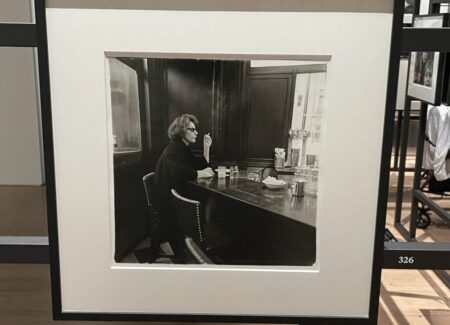

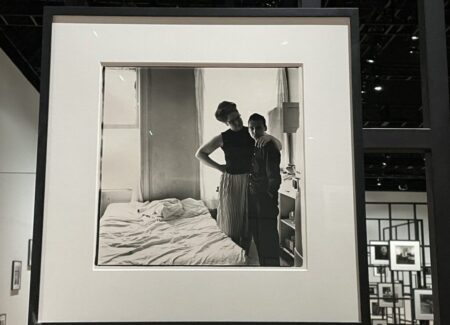

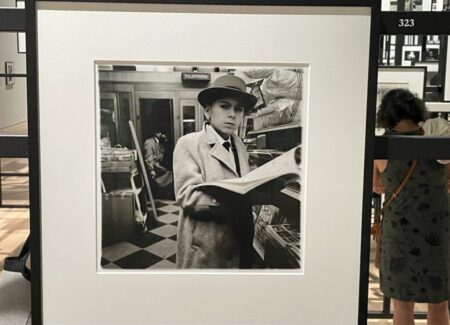

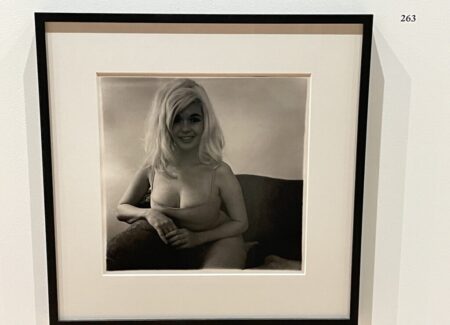

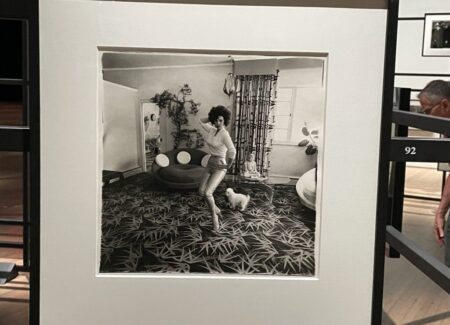

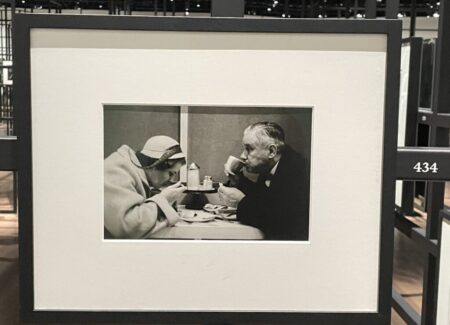

JTF (just the facts): A total of 454 black-and-white photographs, framed in black and matted, and hung on black steel scaffolding and against white walls in the large open space, which includes a mirrored back wall. All of the prints are gelatin silver prints, made by Arbus between 1945 and 1971 and printed by Neil Selkirk. The exhibition includes a chronology and a slideshow of cropped eyes. (Installation shots below.)

Comments/Context: While it might seem like a long time ago culturally, it’s been roughly two decades since Apple introduced its first handheld iPod music players in 2001, adding the radically screenless iPod Shuffle to its lineup in 2005. In the many years since, shuffling has become an industry standard function for music services of all kinds, shifting the way we listen to individual songs. Instead of hearing songs in the order in which they appear on the original albums, we now (often by default) allow the mind of the algorithm to control the sequencing of the songs, in theory introducing pleasingly eclectic randomness into our playlists.

In this way, if you put the entire back catalog of a single decently prolific artist or band on shuffle, what emerges is an endlessly wandering stroll of music, jumping from greatest hits to obscurities to middlers to favorites to duds and back again across time, intermingling hundreds of songs into one creative flow. The original contexts of chronological time period, subject matter, popularity, historical connoisseurship (or quality), and artistic intention are cleanly stripped away, leaving the songs to stand on their own, essentially unprocessed, one after another. And like any playlist crafted without the intelligence of a DJ, the segues and transitions between songs in such a haphazard list can be both unexpectedly quirky and joltingly rough.

The concept of physically putting the collected works of a master photographer on shuffle is of course quite a bit more difficult, which is perhaps why shuffling hasn’t overtaken the art world just yet. The practical problems are many, starting with the unlikelihood of having a career’s worth of photographs in the same physical place. And even if that hurdle could somehow be overcome, perhaps digitally these days, then the issue of arranging or viewing them in some flexible or shuffle-able manner becomes similarly challenging, maybe using dozens of reconfigurable screens or projections. In a sense, the early slideshows of artists like Nan Goldin replicated the one after another presentation of pictures in a shuffled list (often drawing from different artistic periods in her life), but her shows were painstaking sequenced and curated (anything but random), so the analogy doesn’t quite fit; the 2019 survey of Garry Winogrand ‘s color work at the Brooklyn Museum (reviewed here) employed a similar multi-slideshow approach, but again with a tightly curated structure underneath.

Diane Arbus: Constellation is the first shuffled photography exhibition I can recall ever being presented, making it a landmark of sorts. First shown at LUMA Arles in 2023 (here), it is the largest Arbus exhibit ever mounted, weighing in at more than 450 prints from across her career. After Arbus’s death in 1971, Neil Selkirk began to make authorized prints from her negatives for the Arbus estate, and along the way, over some thirty years of making prints, he made one printer’s proof of every negative he printed. This entire set of proofs was acquired by Maja Hoffman and the LUMA Foundation in 2011, and forms the basis of this full career artistic exhibit.

While the black-and-white prints on view here are matted and framed in a traditional manner, they are hung on an unconventional web of geometric steel scaffolding that ably fills the cavernous space of the Park Avenue Armory. The prints are hung at varying heights, high and low and in between, on the “fronts” and “backs” of the armatures, creating a shifting viewer experience of looking up, down, and all around, while drifting through the maze of loosely defined spaces. Aside from one almost “room” that contains the images that were included in Arbus’s “A box of ten photographs” portfolio, there is no obvious ordering applied to the images as hung on the scaffolds (of course, curator Matthieu Humery must have made countless choices about which pictures are placed where, particularly in spatially balancing square format and rectangular prints in different sizes, but the overall effect is altogether jumbled and random.) There is no chronological progression to be followed, no curatorial edit or argument being made, no thematic, location, or subject matter groupings, and no designated or “right” path for a visitor to follow through the exhibit. Many of the framed images have mirrored backs, reflecting whatever is nearby, and a massive mirrored wall at the back then visually doubles the entire installation, further confusing our sense of any order applied to what we’re seeing. In essence, it’s the fabulous everything of Arbus, all on shuffle.

Arbus committed suicide more than fifty years ago, but in the past decade, the interest in her work has remained remarkably high. Gallery shows have featured her photographs made in the park (in 2017, reviewed here), her later “Untitled” works made at residences for those with developmental disabilities (in 2018, reviewed here), and a full restaging of her 1972 MoMA retrospective (in 2022, reviewed here), while a survey of her early works was held at the Met Breuer in 2016 (reviewed here), innovatively installed on partition walls. Add to that Arbus’s nephew Alexander Nemerov’s 2015 memoir (reviewed here) and Arthur Lubow’s 2016 biography (reviewed here) and you have a 20th century artist who has stayed relevant and very much in the 21st century artistic discourse. This full career shuffled show is in some ways the logical end point of this busy activity, pushing out to the broadest edges of Arbus’s legacy.

In all honesty, even though I am a long-time Arbus admirer, my first reaction to this Arbus installation was extremely negative. It felt ungainly (at least compared to a traditional photo exhibit), incomprehensible, performatively showy, and at worst, a kind of cheap novelty (at $30 a head), only one small step up from the tawdry projections of the Van Gogh Experience or Immersive Impressionism. I was frustrated that Arbus had been dumbed down to a flattened and scattered flow, with no curatorial point of view to teach us something new about her art; given the treasured bounty of nearly her entire artistic output, the inexplicably bland choice was made to entertain rather than to thoughtfully educate. “Here’s everything, go figure it out for yourself” seemed to be the imperative, which initially felt like a mystifying abdication of intellectual responsibility.

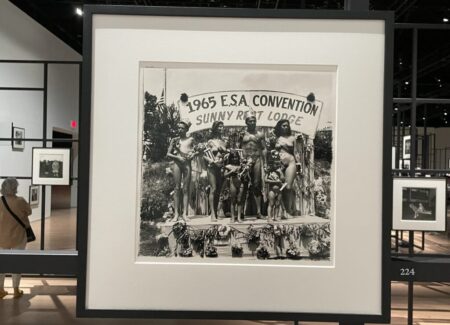

But the fundamental power of the shuffle is that each viewer (or listener) experiences it differently. And as I wandered through the passageways between the scaffolds, I came to a couple of conclusions, perhaps unique to my own prior history with Arbus’s work. The first was that this exhibit was a volume game – its massiveness was part of the message it was sending. And with that volume came a washover feeling of subjects recurring, motifs repeating, aesthetics being refined, and artistic vantage points continually being reconsidered – my brain was trying to pattern match this huge assemblage of images, and eventually, I started to see a sprawling set of links and networks between the images. In many ways, these patterns manifest themselves as a surprisingly consistent photographic vision. We can watch as Arbus wanders the streets of New York (and elsewhere), is drawn to certain kinds of eccentric people, and repeatedly engages them with honesty, dignity, and attentiveness, leading to photographs that thrum with empathetic humanity, again and again and again and again. Drifting through the installation is like tagging along on a stroll through Arbus’s marginalized world, where the people that caught her eye back then now catch ours. And as my time spent in the installation increased, the connections and network nodes felt like they were being multiplied, like musical harmonies or refrains on repeat.

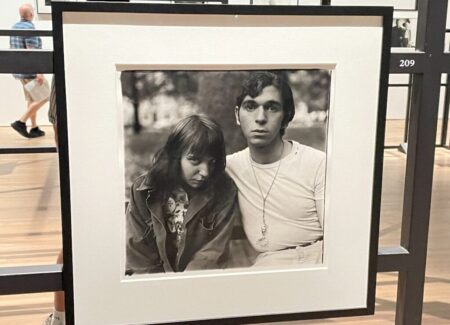

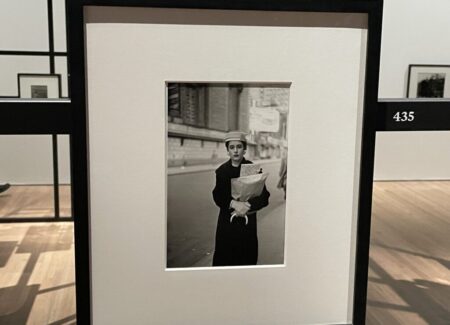

My second observation is that the shuffle-ization of Arbus’s catalog had the effect of aiming my attention at the most obscure pictures in the installation. Perhaps for some, the familiarity of some of Arbus’s most well known photographs would be a logical visual anchor point, and with these icons scattered around the room, perhaps the show might feel like a treasure hunt, with old friends hidden around every corner. For me, it was just the opposite – my eyes glossed over the usual suspects, and instead seemed to search out the pictures I hadn’t ever seen, or had previously overlooked, forgotten, discounted, or underestimated. A couple of handfuls of these images can be found at the end of the installation shots above; depending on your own familiarity with Arbus’s oeuvre, perhaps you will wonder about why I didn’t remember or appreciate these enough, but the shuffle mechanism made them feel like new discoveries to me. And when I look at these few images now, I’m struck by the consistent strength of the gaze Arbus has captured – in nearly every picture, even in the three hundredth or even four hundredth most well known image made in her career, the intense eye-to-eye connection is like lightning in a bottle. To me, that hit home as irrefutable evidence of an incredibly deep and enduring talent – when the rarities and never seens are this impressive, there’s a lot more than artistic luck taking place.

I’m sure that many of you will wonder about my sanity in giving the entirety of Diane Arbus’s photographic career a rating of one star. But even with the positives outlined above, and the real joys of seeing so much superlative photographic excellence (and personal trust) on view in one place, I remain flummoxed by this exhibit and its choice to frame itself as an open-ended, readily-consumed entertainment experience. I think the take-away is that I just don’t want to see the durably important work of Diane Arbus on shuffle, and that you won’t have missed much if you fail to make it to the Armory this summer. In the end, I want to try to meet Arbus with as much actively engaged intelligence and nuance as her most provocative work deserves, rather than simply tossing her accumulated creative output into the air and letting the images passively scatter and fall where they may.

Collector’s POV: Since this is essentially a museum exhibition, there are of course no posted prices. Arbus is represented by David Zwirner in New York (here) and Fraenkel Gallery in San Francisco (here). Her prints are ubiquitous at in the secondary markets, in both the photography and contemporary art sales. Recent prices have ranged from roughly $5000 (for lesser known images and posthumous prints by Selkirk) to just under $1200000 (for vintage icons printed by Arbus).