JTF (just the facts): A total of 93 black and white photographs, framed in black and matted, and hung on both sides of an array of thin grey partition walls on the second floor of the museum. All of the works are gelatin silver prints, made between 1956 and 1962. The exhibit was organized by Jeff Rosenheim and will travel to SFMOMA in 2017.

The show also includes two side rooms: one containing 9 additional Arbus works (1963-1970) from her A Box of Ten Photographs portfolio (the 10th print is on view in the main space), and another containing a selection of works by Leon Levinstein, Sid Grossman, Walker Evans, Helen Levitt, Lisette Model, August Sander, Lee Friedlander, Robert Frank, Garry Winogrand, William Klein, and Louis Faurer, with 6 additional works by Arbus.

A comprehensive exhibition catalog has been published by the museum (here). Hardcover, 256 pages, with 105 black and white reproductions. Includes essays by Jeff Rosenheim and Karan Rinaldo. (C0ver shot below.)

Comments/Context: Only a vanishingly few prodigies ever arrive into the art world with a largely mature style. Almost by definition, the vast majority of artists go through extended periods of hard work, trial and error, and ultimate slow transformation, where flashes of ideas kick off rounds of experiments, some of which lead to breakthroughs, and are then consolidated into something authentically and durably original over time. When we focus in on an artist’s high points and masterworks, we often tend to gloss over this earlier period of groping in the dark. But with the benefit of hindsight, it is often possible to see traces of an artist’s later mature style in his or her early efforts, and this backward following of breadcrumbs helps us understand the important choices and trade-offs that were made along the way.

When Diane Arbus took her own life in 1971, many would argue that she was at the height of her artistic powers. The late 1960’s had been a productive time for Arbus – her second Guggenheim award, the New Documents show at MoMA with Friedlander and Winogrand, and an increasingly steady stream of magazine assignments, travel, and teaching opportunities. Stylistically, Arbus had moved to the 2¼ inch square format Rolleiflex camera in 1962, and it is her crisp square prints from the last decade of her life (some of the most memorable images being collected in her 1971 portfolio A Box of Ten Photographs) that mark the apex of her work.

But Arbus had begun her independent artistic career in 1956, when she and her husband Allan ended their artistic partnership (she was the art director/stylist, he the photographer) and she first ventured out on her own. This initial period was loosely chronicled in the blockbuster 2003 retrospective Diane Arbus Revelations, with several dozen prints from these early years on view. But it wasn’t until 2007, when her daughters Doon and Amy Arbus donated an extensive selection of unpublished photographs from the 1950s to the Met (along with countless notebooks, diaries, appointment books, glassine negative sleeves, and other ephemera) that it became possible to truly make an in-depth study the early period of her career. This exhibit is the result of that decade-long effort to rationalize the archive.

The most straightforward curatorial approach to this material would have been to meticulously order the photographs chronologically, so we could see how Arbus chose her subjects from year to year, and how small stylistic differences were tested and either amplified or abandoned over time. But curator Jeff Rosenheim has opted for something more atmospheric and open-ended, which has its own strengths. Hung against an arrangement of thin partition walls, with a single image on each side of a vertical slice, Rosenheim has effectively forced us to see each image as a stand alone entity, without the benefit of before or after context – there are no thematic, aesthetic, or geographic groupings of any kind. The result is that the entire sweep of years between 1956 and 1962 becomes an integrated survey of amorphous, searching, early stage experimentation, rather than a step-by-step progression.

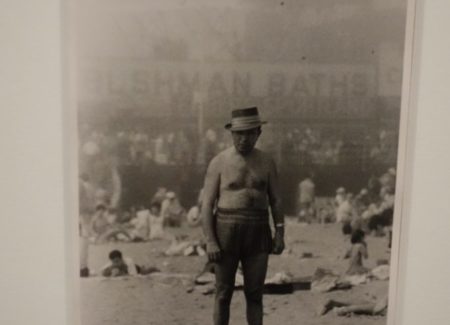

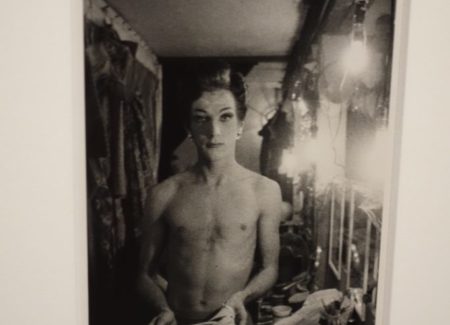

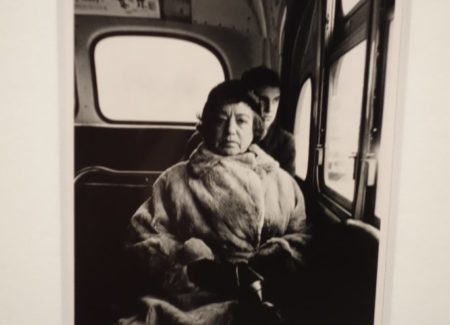

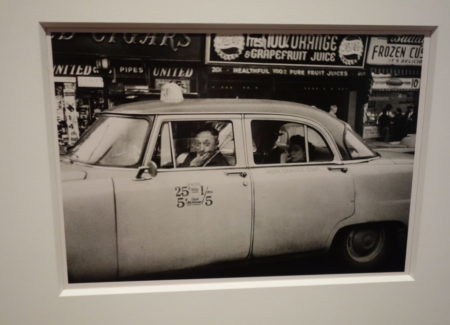

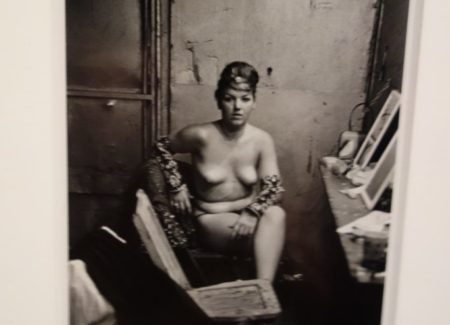

Given what we already know about Arbus and her affinity for getting empathetically close to the eccentric and the marginalized, these early pictures are like a test sheet for her evolving personal interests – some ideas turn out to be rich and multi-dimensional, while others never quite connect. From the very beginning, her sidewalk portraits extended to the overlooked – children, older folks, young couples – and walking the streets and riding the bus, she was particularly attuned to signifiers of social class, especially the furs, white gloves, and jeweled brooches of women of a certain age and bearing. When she went hunting for odder extremes (her daybook lists of topics, themes, and possible subjects are exhaustively quirky), she started with classic New York haunts like Coney Island and Times Square, capturing the faces of sideshow performers, strippers, and female impersonators (flexible gender was another recurring motif), initially with arm’s length timidity, and later with more direct confidence.

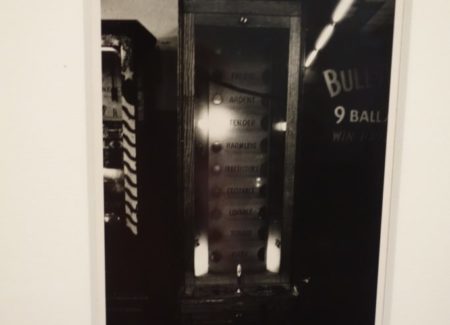

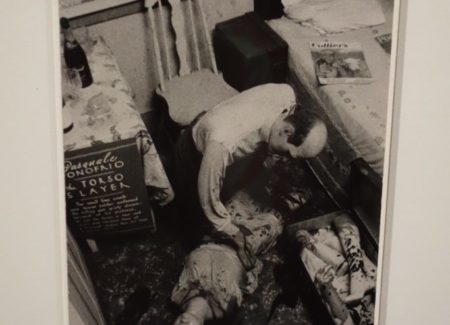

This gradual building of ambitious self-assurance is the single most important discovery in these early pictures. As evidence of her initial tentativeness with engaging her subjects, there are many more still lifes and people-less pictures in these images than in her later work. And her choices point to much darker impulses and fantasy scenarios than she would normally find on the streets – axe murderer setups in wax museums, Siamese twins in a jar at the sideshows, decaying corpses at the morgue, dead pigs hanging at the slaughterhouse, and a repeated interest in taking shadowy stills at the movies, snatching kisses and horror screams with equal energy. Other subjects were just wonderfully, eye-catchingly weird – the moving rocks on wheels at Disneyland, a tombstone for “Killer” in the pet cemetery, and the mood meter machine at the sideshows, with light-up options ranging from frigid to fiery.

But it is clear from this selection of images that Arbus was slowly building her nerve over these initial years. While it is difficult to make any sweeping generalizations without seeing the pictures in strict chronological order, Arbus was undeniably employing a range of engagement strategies at this point, from indirect, snatched images of unsuspecting strangers on the street all the way to dead-on eyes-in-the-lens portraits that required trust and interdependence between the photographer and sitter. As we know in her later work, this unvarnished, often risky-to-both-sides, intimate style of portraiture became her signature, but here it comes and goes, intermingled with pictures that have more introspective distance and reserve. These photographs show both her irrepressible curiosity and nonjudgmental point of view, but her later work refines these encounters into something sharper and more explosive. Perhaps the conclusion is that in the 1950s and early 1960s, she was incrementally learning how to successfully interact with people she didn’t know well, and it took her nearly a decade to master those skills enough so that she could leverage them into indelible portraits.

The other important vector to consider in these early pictures is the stylistic changes that are going on. Nearly all of the images from this period were taken with her 35mm Leica, so they don’t have the tightness of the square format that would later be a critical component of her mature aesthetic. Here the rectangles in horizontal and vertical alignment give her sitters more space, with long coated ladies and movie stills extending in the frame. Additionally, many of her images seem to dissolve into thick tactile grain, as if a muddy mist was lingering over the city, especially after nightfall. This almost impressionistic semi-blurred grit goes away by the end of this early period, to be replaced by a more unflinching and penetrating gaze.

This exhibit, and the well crafted catalog that accompanies it, is all that we could hope for in terms of a thorough, academically rigorous investigation of the first chapters of the Diane Arbus story. And while some of that precision is deliberately removed by the unexpected pillar-style installation and the all-at-once organization of the prints, the raw material is certainly now available for those who want to dig deeper and draw their own conclusions – the Met has admirably done its duty to the gift from the estate.

What sticks with me most from this show is the palpable sense of the jangly-nerved Arbus just getting started, heading out on artistic expeditions around New York, armed with her endless lists of eccentric topics to be on the lookout for. She hadn’t yet figured out a lot of what would make her great later on, but her eagerness to roll up her sleeves and wrestle with the gritty underbelly life is right there on the surface of her initial efforts. The essence of her latent talent lingers in these first impressions, and while they aren’t all entirely memorable, each and every one represents an adventurous challenge for an aspirational young artist trying to find her voice.

Collector’s POV: The estate of Diane Arbus is represented by Cheim & Read in New York (here) and Fraenkel Gallery in San Francisco (here). Arbus’ prints are ubiquitous at in the secondary markets, both in the photography and contemporary art sales. Recent prices have ranged from roughly $5000 (lesser known images/posthumous prints) to nearly $800000 (vintage icons).

Insightful review.

Thinking about Arbus today while at work, how incredibly articulate – and candid – she was in her writing both about photography and herself. It’s also surprising that someone so intellectually capable, and from such a privileged background, should actually have gone out and done what she did.

I went to the exhibit today (thoughts noted here, http://www.goldcompanions.org/single-post/2016/10/22/The-King-and-Queen-of-the-Senior-Citizens-Dance-Diane-Arbus-at-the-Met-Breuer) and have been surfing the web to find reviews and critiques such as this one.

Please accept a possibly contrarian viewpoint here for the sake of discussion. I was not extremely moved by her portrayal of gender. Indeed, with her reputation as a documenter of the absurd or socially marginalized, her pictures of what were labeled “female impersonators” (i.e., drag queens) served instead to reinforce heteronormative ideas.

It’s probably inappropriate to speculate on the causes of her suicide (who could ever really know?) but could have profiteering (for her family’s financial legacy, if not her own, although she did do okay in her lifetime) and exploiting the suffering of the marginalized weighed on her conscience? Indeed, as a woman who was born into considerable financial means, could her documenting the lower classes for profit and amusement truly be praised as socially responsible rather than exploitative?

Her photographs displayed an incredible amount of skill, and I commend them. The exhibit is worth seeing.