JTF (just the facts): A total of 35 black-and-white photographs, framed in black and matted, and hung against white walls in the main gallery space. (Installation shots and film stills below.)

The following works are included in the show:

- 29 gelatin silver prints, 1967, 1967/1969, 1968, 1968/1969, 1968/1970, 1968/1970s, 1969, sized roughly 6×6, 6×9, 6×10, 7×12, 8×11, 8×12, 9×5, 9×14, 10×10, 12×8, 13×19, 14×10, 22×18 inches

- 1 gelatin silver print with hand decoration, 1968/1968-1970, decorated early 1970s, 8×10 inches

- 5 gelatin silver prints, 1967/later, 1968/later, 1968/1991, sized roughly 11×14, 16×20, 28×39 inches

- 1 audio recording, 1968

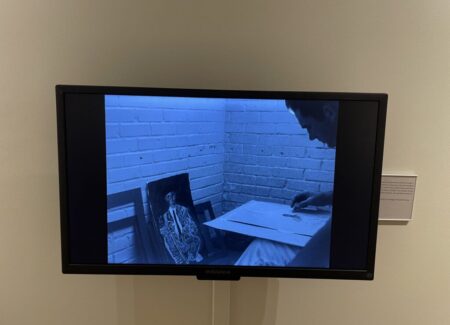

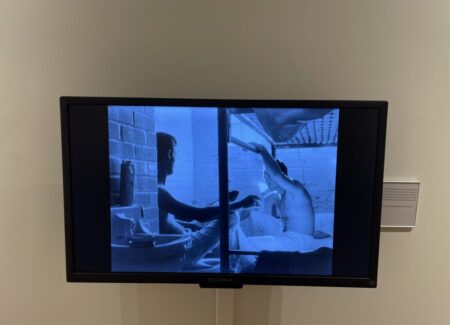

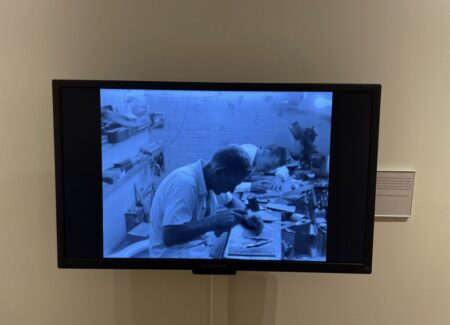

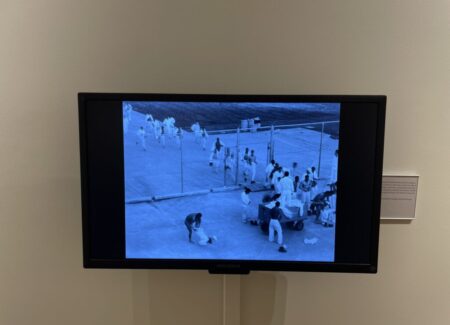

- 1 16mm black-and-white film footage, 1968

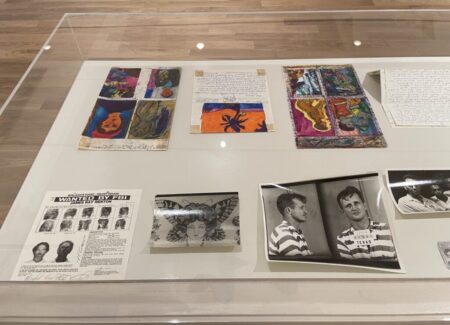

- (vitrine): miscellaneous images, FBI wanted poster, prisoner letters/drawings, exhibition announcement, decorated print box

Comments/Context: One of the main reasons that Danny Lyon’s photographs from the 1960s and early 1970s have remained so astonishing vital is that they deliberately broke the rules of documentary photojournalism. Lyon wasn’t interested in playing the role of a cool dispassionate photographic observer, examining any given situation from an arm’s length distance, staying outside and uninvolved so he could remain objective. He was instead altogether engaged, subjective, personal, and passionately participatory, to the point that he was often thoroughly mixed up in the lives of his subjects. This unabashed insider perspective offered a new sense of intimacy, urgency, and immersively authentic truth that we really hadn’t seen before (and that became part of a larger movement called “New Journalism”), which still feels entirely risky and radical even half a century later.

The now decently well known arc of Lyon’s career typically starts with his images of the Civil Rights movement in the early 1960s, followed quickly by his revolutionary project documenting the Chicago Outlaws motorcycle club, which ultimately took shape as his iconic book, The Bikeriders. (This progression is thoughtfully laid out in his 2016 Whitney retrospective, reviewed here.)

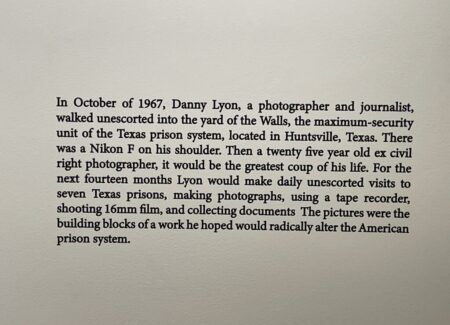

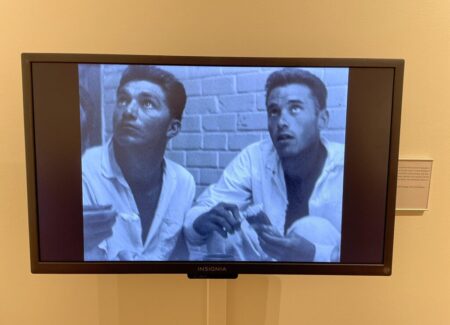

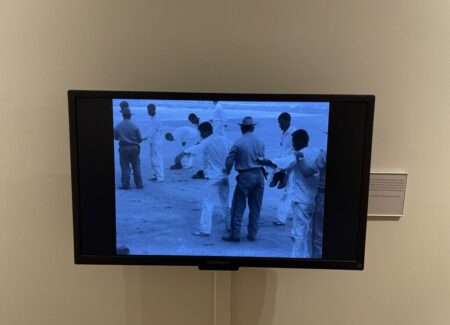

What came next chronologically, in 1967 and 1968, was a deep dive into the Texas prison system. Lyon was given unprecedented access to a total of seven Texas penitentiaries – he could largely come and go when he pleased (day or night), and he could photograph the men in their cells, on the cell block, in the cafeteria, in the fields and factories where they worked, and even in isolation and during shakedowns. He spent a total of 14 months on the project, making a range of photographs, audio recordings, and short films, and gathering up all kinds of ephemera, including letters and drawings from inmates (many of whom he continued to correspond with for years) and other prison documents. Lyon’s photobook presentation of the project, Conversations with the Dead, was published in 1971, and has at this point solidified its place as a landmark in this history of the medium.

Given the consistent quality of the photographs and the artistic durability of the project as a whole, Lyon’s Texas prison pictures have re-emerged several times in recent years – in a 2015 gallery show (reviewed by Richard B. Woodward here), in his 2016 Whitney retrospective, and now again in this 2026 gallery show, on the occasion of a new gallery representation relationship established between Lyon and Howard Greenberg Gallery. So we have indeed seen many of these pictures (or their variants) before, but that doesn’t dilute their indelible persuasiveness and importance. That there are as many superlative vintage prints from this project still running around (enough to essentially fill this show, with a few later/larger prints sprinkled into the mix) is honestly somewhat surprising.

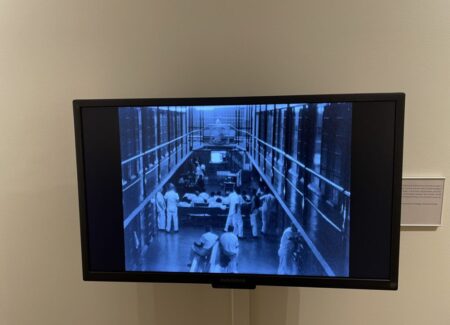

One way to place what is on view here in an aesthetic framework is to break the pictures down into groups of photographs alternately made inside and outside, as Lyon had to use different photographic strategies in each case. Inside, Lyon made smart use of the physical framing of the prisons, with fences and walls of bars repeatedly screening the prisoners, and peep holes and doors creating bounded opportunities to see inside – most of Lyon’s pictures inside the prisons used these hard edged features of the environment to remind us being closed in, our seeing constantly interrupted, broken up, and limited, just like an inmate’s.

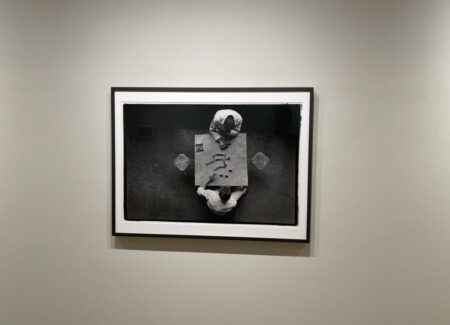

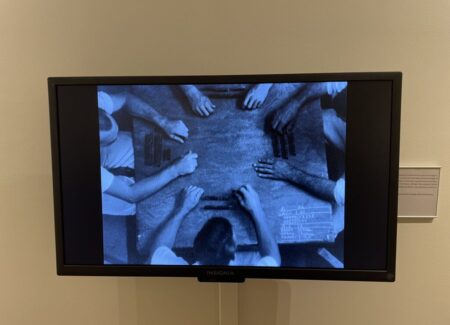

Lyon also used the available light with mastery. With prisoners outfitted in full length white jumpsuits and the light often filtered from exterior windows or flared from single bare bulbs, bright contrasts of monochrome light and dark were consistently available, and compositionally Lyon made the most of them to backlight or silhouette figures, to create dappled areas of whiteness amid the dark gloom, and to create ethereal almost religious glows that amplify the emotional range of the scenes. A famous image looks down on two inmates playing dominoes on a cell block table, but other portraits feel even more poignantly intimate, with faces framed by bars, bodies standing in iron doorways, and gestures made from behind walls of bars, each individual (as named in titles and captions) seen with attentiveness, compassion, and genuine connection.

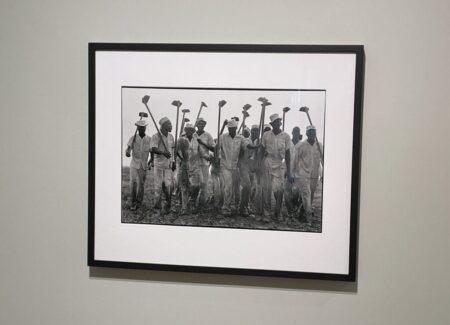

While the appearance of casual ease and personal identity filled many of Lyon’s interior images, his images outside tended to feature groups of men who were largely anonymous. The white clad figures cluster in groups and bunches – picking and hauling cotton, chopping down trees, riding in trucks, and tilling the soil with hoes – their jumpsuits and hats creating patterned spots of white and ordered lines across Lyon’s compositions. The work was clearly physically hard and exhausting, with the Texas heat taking its toll – Lyon’s images document several fallen bodies carried out of the fields and placed in the back of trucks to be transported away. Small moments of camaraderie among the prisoners are visible here and there, with smiles breaking out during periods of rest or when the day’s work was done, but the harsh menace of the system was never far from view, often in the form of looming cowboy-hatted guards on horseback, their physical position above the prisoners always amplified. One particularly ominous image shows a tangle of handguns dangling on a hook being dropped down from the prison tower to the guards outside, with a loose line of prisoners in the distance, the threat of violence visible for all to see. The days outside then end with hurried shakedowns, each prisoner patted down and searched in succession, arms outstretched with obvious symbolism.

Conversations with the Dead was one of the first photobooks to integrate ephemera into its narrative, and a vitrine of personal letters and drawings from inmates reinforces how richly important this material was to the empathetic human story Lyon was trying to tell. Lyon himself would also start to make his own handwritten annotations and decorations on his prints to give further context to his images, as seen in a repeated film still print to which Lyon added his own frustrations with the realities of incarceration he witnessed firsthand.

While long-term embedded photojournalism has come a long way since Lyon’s days in the late 1960s, his Texas prison pictures still have plenty to teach us, particularly about how photography can be convincingly used to tell complex visual stories. As tough and raw as the prison subject matter is (Lyon even offers us a grim view of a prison guard posing near “Ole Sparky” the electric chair), humanizing compassion thrums through Lyon’s consistently elegant images. Lyon later said that “Texas would change my life,” and his photographs still have the power to change ours, if we meet them with the same engaged openness with which they were made.

Collector’s POV: The prints in this show are priced between $7000 and $40000 each, based on size and print date. Lyon’s work is consistently available in the secondary markets, with recent single image prices at auction ranging between roughly $1000 and $53000.