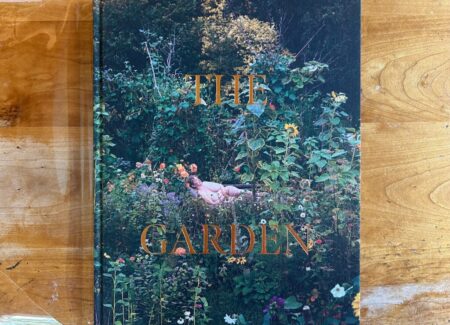

JTF (just the facts): Published in 2024 by Trolley Books (here). Clothbound hardback with foil stamped title, 34 x 26 cm, 112 pages, with 80 color photographs. Includes essays by the artist and Jennifer Higgie. Design by Emma Scott-Child. (Cover and spread shots below.)

Comments/Context: With Memorial Day fading in the rear view mirror, summer has unofficially begun. For those of us in the global north, these are the months we look forward to throughout the dark winter. ‘Tis the season of longer days, bare skin, outdoor leisure, and verdant backdrops. If we’re lucky it might include a family gathering, a ninth inning rally, or a bountiful garden. Life is good. Summertime and the livin’ is easy.

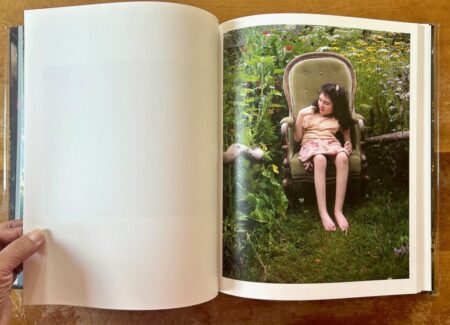

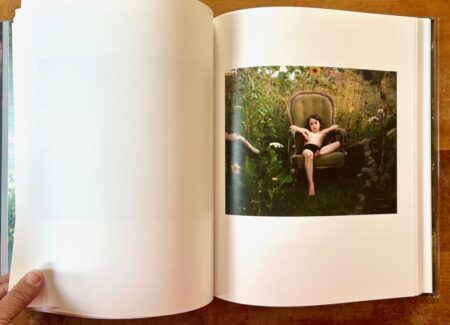

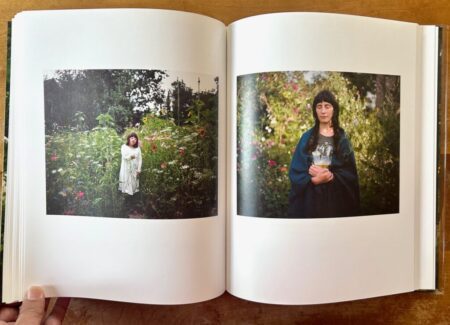

If it all sounds rather Edenic, this is the aesthetic realm of The Garden. Siân Davey’s latest photobook of portraits is a large hardcover with an overgrown presence. Physically speaking, it’s an order of magnitude bigger than either of her two previous Trolley monographs. Once you’ve bushwhacked into the interior, deep green tones dominate the photographs, speckled with a rainbow of wildflowers. The pictures were staged and shot in Davey’s backyard over the course of three consecutive summers, 2020 through 2022, with assistance and inspiration from her adult son Luke Davey. “Why don’t we fill our back garden with wildflowers and bees,” he suggested one midwinter (Collector Daily’s Loring Knoblauch had the same gardening impulse recently), “and the people we meet over the garden wall, we’ll invite them in to be photographed by you.”

Luke’s initial proposal is recounted in Davey’s introduction. Left unwritten are a few additional variables. As she began the project, Davey was still familiarizing herself with her new home and its neglected garden space, having recently resettled from city life in Brighton to the countryside near Totnes, Devon. The other X factor was the Covid pandemic and its widespread disruptions. Not only was Davey’s habitation in flux, the whole world was teetering. It seemed only reasonable to seek stability and creative potential in nature.

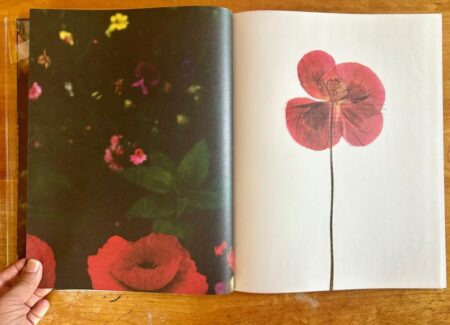

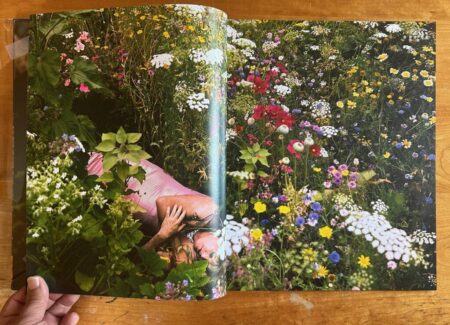

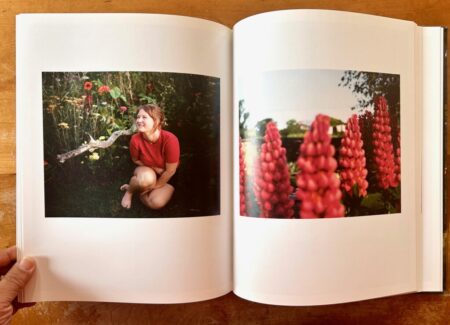

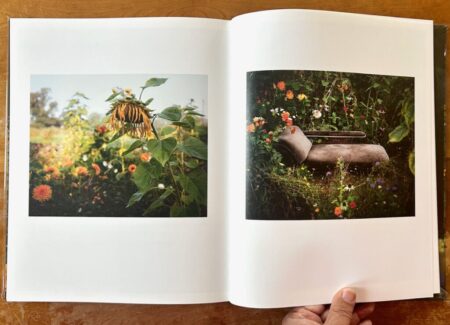

Do not be misled by the title. Davey’s garden is not a typical English garden with formal rows and syncopated blooms. Instead her yard is more of a domestic jungle, with every blossom playing in unison. Vegetation pushes against the book’s rectangular confines. Weeds and flowers—maybe the difference here is semantic?— sprout head high. Mullein, meadowsweet, wild carrot, sunflowers, poppies, cornflowers, gourds, tromboncinos, and sweet peas buffer thick towheads of grass. Surrounding trees shade the main space with claustrophobic intensity. It doesn’t seem that any stems have ever been pruned, harvested, or mowed. Why, it’s a regular plant utopia. Is this where vegetation crosses the rainbow bridge to heaven?

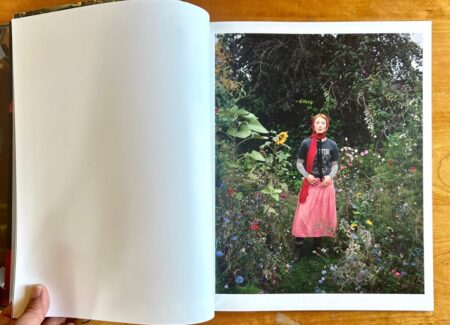

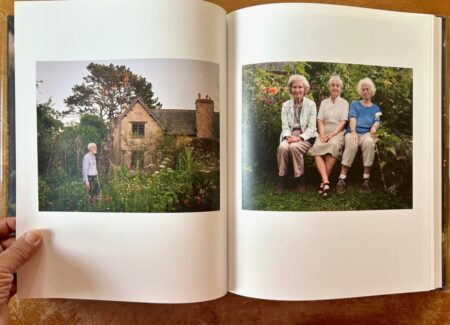

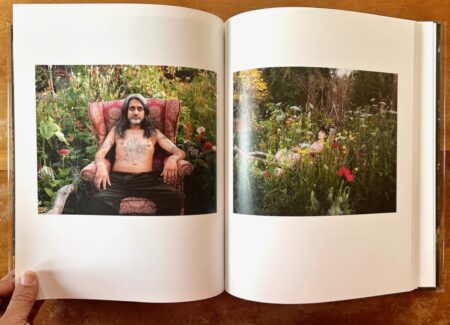

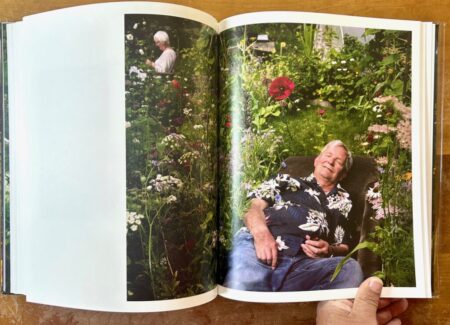

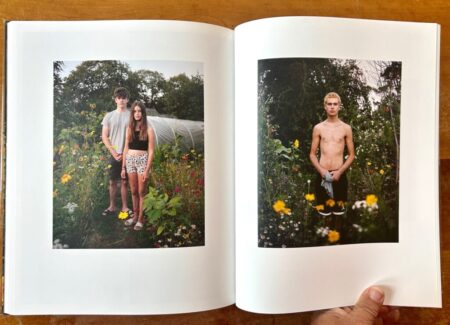

Perhaps, but let us reground a moment. Floral fantasies aside, Davey’s yard is an earthly paradise for humans as well. Dozens of people appear in the book, all in various states of tranquility. If we take the Daveys at their word, most were initially engaged through chance meetings, met beyond the wall, then lured into the private garden for portrait sessions. A few ringers appear alongside these strangers, including Martin Parr and Davey’s daughters Alice and Martha (the subject of her previous photobook reviewed here). There may be other friends and family included, but without identifying captions it’s hard to separate them. In any case, most portrait subjects were previously unknown to Davey.

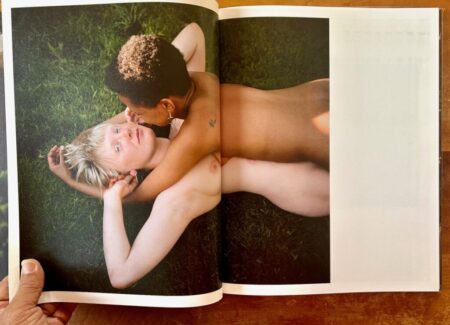

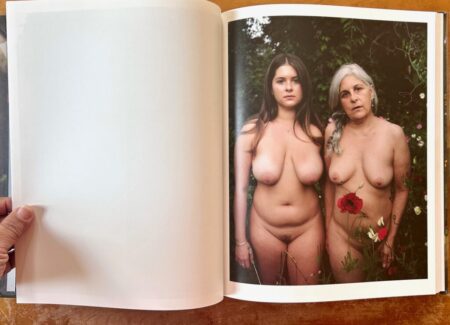

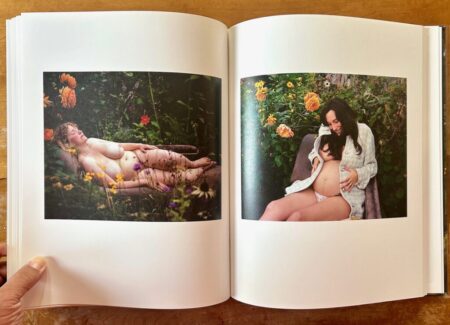

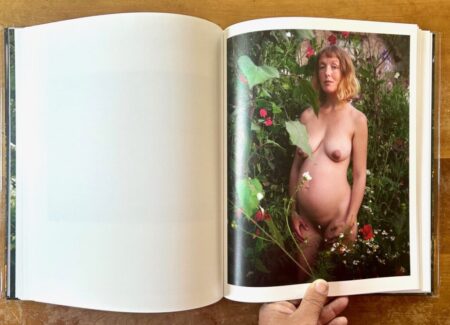

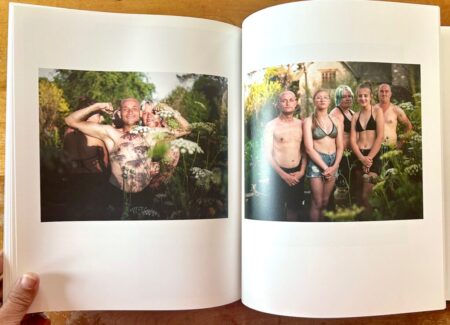

The initial pages frame the general setting, while hinting at the potential dynamics for luring sitters. Davey shows two photos of idling men, each one viewed a short distance behind her garden wall. On the next spread, a man holds a dog leash and young child, both possible conversation starters. Most photographers would have trouble converting any of this material into good portraits. For Davey it’s a cinch. Soon enough she’s into the main sequence, coaxing one intimate revelation after another. Young trios nestle in the shrubbery, a grey haired man gets a facial massage, and naked lovers embrace on the grass, with the bottom figure gazing back at Davey over the top’s shoulder. A nod to Stephen Shore’s couch portrait of Michael and Sandy Marsh? Perhaps. A few pages later, a 3/4 vertical of naked mother and daughter floating against a primordial green backdrop feels like a scene from alt-Genesis.

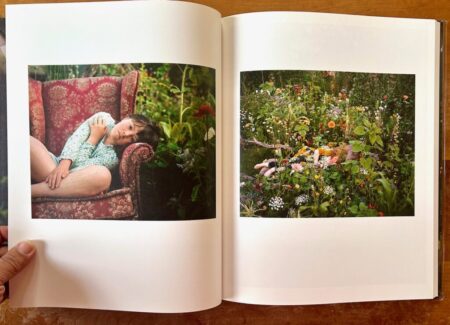

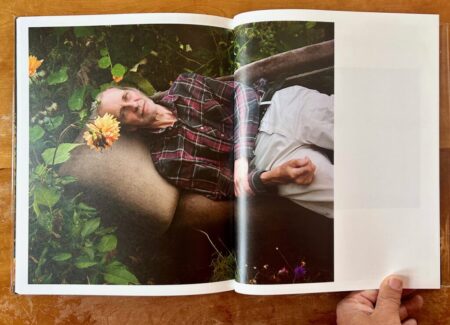

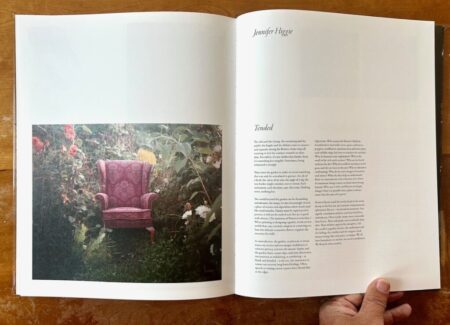

As easily as Davey cajoles her subjects to shed their garments, we’re spellbound by her portrait style. Her stagings somehow feel both breezy and reverential. Some subjects are young, some old. Some clothed, some nude. Some single, some families. All are deeply meditative. Davey uses a medium format film camera for natural color, typically shooting at open apertures to isolate skin and textile. Clothing patterns sometimes match the design of the upholstered chairs which she uses as garden props. She employs this furniture and an occasional pillow to good effect to pose her subjects seated or reclining. A few have managed to fall asleep altogether, perhaps dreaming of fish jumping or high cotton.

How was Davey able to seduce passing neighbors into such extraordinary moments of vulnerability? What was her secret? Well, before taking up photography she had spent 15 years as a psychotherapist (one of her garden seats resembles a therapist’s couch). So she had well developed interpersonal skills, and an ability to read gesture and expression at a glance. Her transcendentalist outlook probably didn’t hurt the cause. Here is Davey describing her creative process: “As the garden evolved it became an expression of joy, interconnectedness, yearning, sexuality, and defiance. The garden became a metaphor for the human heart itself. Those who entered the garden reflected back to me my history and who I had become. Everyone has a place in our garden. I am the garden. Those who enter are the garden. Without distinction, without separation.” If the explanation feels New Agey, the final proof is in the photo pudding.

Davey’s website includes a 20 minute video meant to accompany the book. It is a wordless collage of film clips showing Davey’s subjects in the process of being photographed. Several portrait subjects appear in both the video and the book. For process-curious fans, they’re a view behind the curtain, the rough equivalent of a magician revealing her secrets. The contrast between film and book is stark. Whereas the final portraits are confident and magisterial, the film sequences are restless and scattered, with blown out light leaks adding a lo-fi touch.

A tattooed man fidgets for minutes in one clip. His feet bounce and his fingers twiddle, as if he can’t decide what to do with his hands or where to look. He’s a million psychic miles from the commanding portrait which appears in the book. In the next clip a group of young people flexes and preens, mingling on the outer verge of photo potential. In another long scene, a young girl struggles to keep a straight face while waiting for Davey to do her business, which seems to be taking for-eeeeev-er. Meanwhile Davey is shown here and there in the video, smiling calmly to herself while she manipulates her hand-held camera. Watching this compilation of raw material shot in real time, her ability to seize the moment feels ineffable. Converting real life into good portraiture requires sensitivity, patience, and a bit of luck. A background in psychotherapy comes in handy too. But even when all these ingredients are blended, the alchemy is mysterious.

After watching the film, Davey’s achievement feels even more impressive. From a flurry of floral and nervous energy, she has plucked yet another solid body of penetrating portraits. The Garden fits naturally into her oeuvre alongside Looking For Alice and Martha. In the broader context of photographing strangers in situ, it slots alongside minor classics like Irina Rozovsky’s In Plain Air (reviewed here), Donavon Smallwood’s Languor (reviewed here), and Judith Joy Ross’ Photographs 1978-2015 (reviewed here). With warmer days on deck, it should provide for pleasant summer browsing.

Collector’s POV: Siân Davey is represented by Michael Hoppen Gallery in London (here). Davey’s work has little secondary market history, so gallery retail remains the best option for those collectors interested in following up.