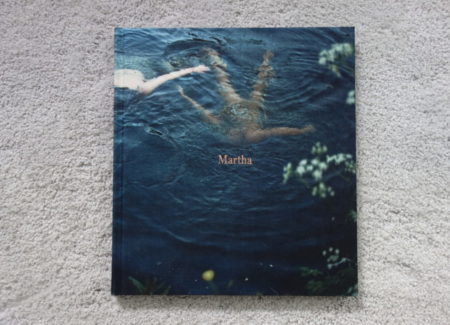

JTF (just the facts): Published in 2018 by Trolley Books (here). Hardcover, unpaginated, with 51 color photographs. Includes two short essays by the artist and a foreword by Kate Bush. Design by Emma Scott Child. (Cover and spread shots below.)

Comments/Context: Few photobooks I have come across in recent years have felt as pitch perfect to me as Siân Davey’s Martha. In many ways, it’s a modest project – a stepmother’s effort to make pictures of a teenage daughter’s growth into young adulthood – but as the parent of two teenagers myself (ages 18 and 15), I can attest that what Davey has accomplished here is both right on the mark and quietly and touchingly memorable. And after spending time with Martha, I forced my wife and daughter (together) to take an extended look at its pages, which is something I almost never do when writing about a new photobook.

Davey first came to the attention of the photography world with her 2016 photobook Looking for Alice, which sensitively chronicled the life of her daughter Alice who has Down syndrome. And it was that effort, and the accompanying overload of attention paid to her much younger sister, that led older sister Martha to one day ask “why don’t you photograph me anymore?” Coming from a 16 year old (Martha’s age at the time), who was by definition acutely aware of herself and her uncertain place in the world and who might not generally find the intrusive attention of her stepmother’s camera exactly desirable, this question (and its implicit request) was certainly unexpected, and formed the impetus for Davey’s next body of work.

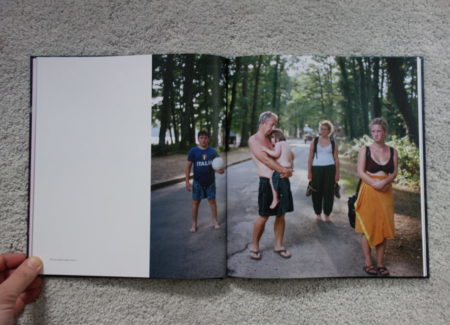

Over the next three years, Davey photographed Martha – on her own, in the context of the family, and with a growing group of friends – watching as she traveled the bumpy roads of growing up. That Martha allowed Davey inside her private life (into her moods, among her friends, etc.) with such openness and trust is in many ways astonishing, and Davey seems to have earned that special place inside the inner circle by finding ways to be present without disrupting the natural (and sometimes awkward) flow of events taking place.

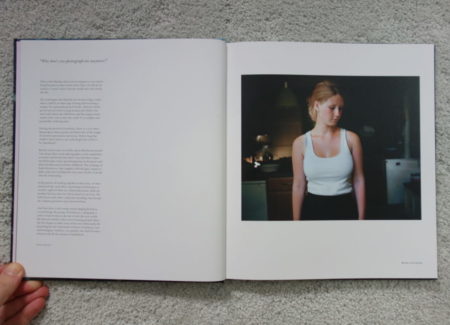

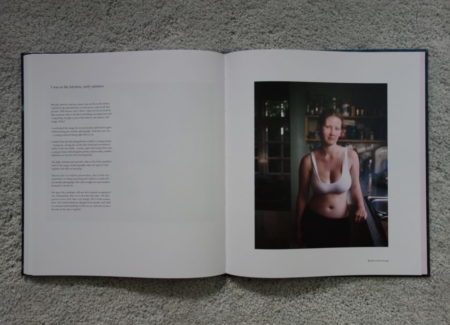

The book is arranged in a roughly chronological sequence, the photographs bookended by two portraits of Martha standing in the kitchen, one at the beginning of the project and one essentially at the end. In the first, Martha looks away, the tiny nuances of the sheen on her skin and the way she carries herself alluding to her relative innocence and her general discomfort with being looked at. Three years later, she stands with much more confidence, at ease with her own body and skin, with a look mixing a mild degree of annoyance at (and acceptance of) the process and the knowledge that she is more of an equal now than a subject. While the two images are superficially the same, they speak volumes about Martha’s changes and transitions over the intervening years.

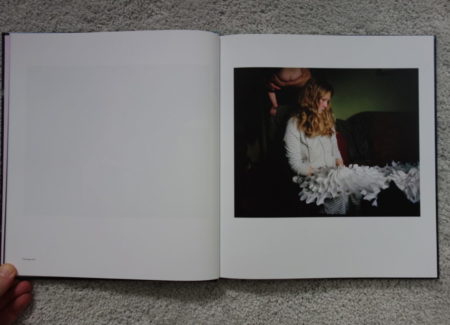

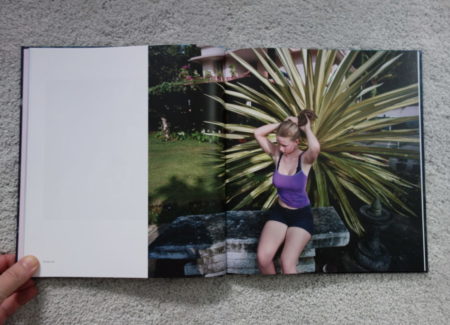

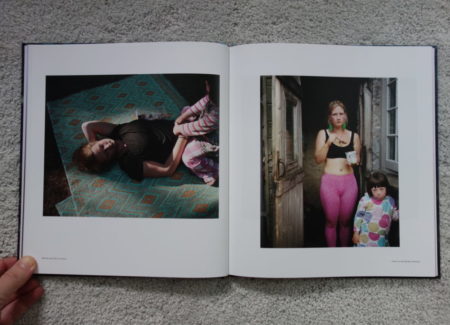

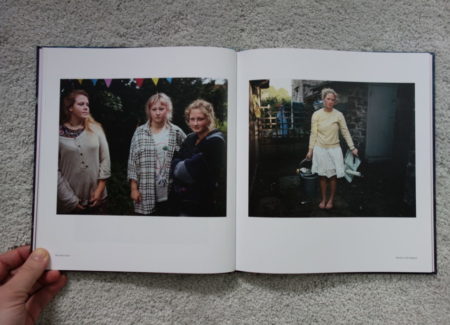

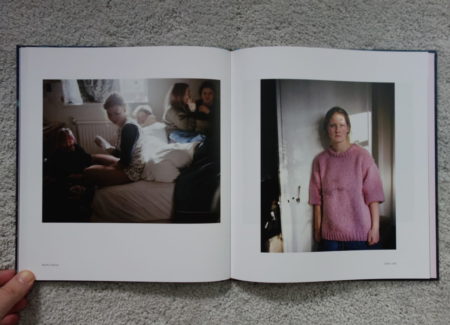

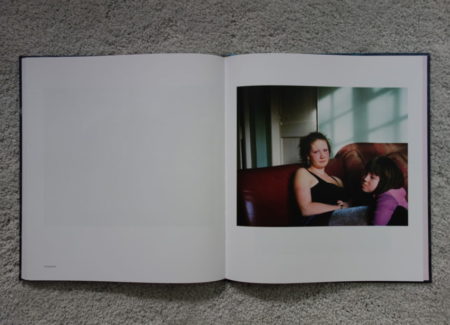

Most of the first third of the book sets Martha in the context of the family, her personality constantly bounded by those around her. Her moods consistently settle into the lower registers, with boredom matched by introspection, embarrassment coupled with dutiful attendance to child care and household chores, and resignation matched by the understated horror at what her family might do next. In many cases, she has the look of someone who would like to be anywhere but where she actually is, and the only smile in this first section comes with the introduction of her friends, where we start to see her finding a first glimpse of guarded ease. Overall, it’s the small details that give these pictures their added resonance – the bare toddler’s bottom intruding into the dull preparation of paper snowflake decorations on Christmas Eve, the reluctant mirrored hesitation at the barber shop on vacation in India, the explosion of plant leaves behind Martha as she ties up her hair, and the tongue-stuck-out face of her younger sister as she echoes her sister’s long-suffering ice-cream-eating expression. While there might have been moments of joy elsewhere in their lives together, Davey has mostly chosen to show us Martha actively wrestling with (and being frustrated by) her desire for more freedom and space from the constraints of family.

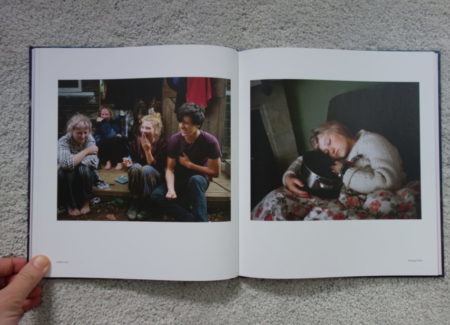

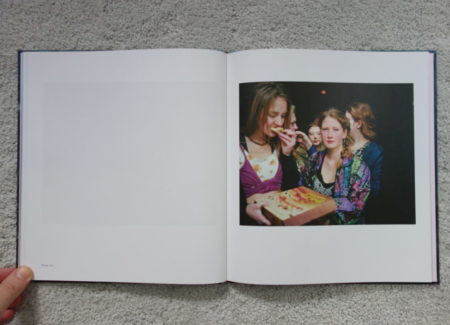

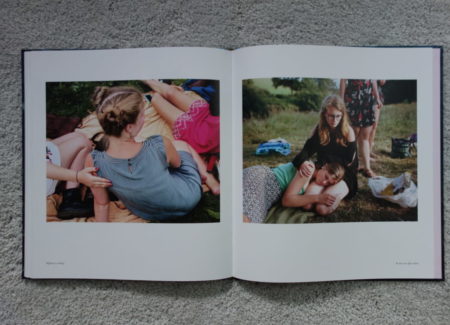

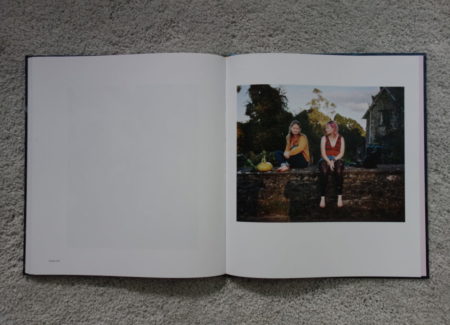

In the middle portion of the book, Martha starts to spread her wings a bit, tentatively stepping out into more adult situations. We watch as she gets ready for prom with her girlfriends (where piercings and makeup anchor the looks) and hangs out with boys at the afterparty. Her circle of friends seems to widen, and new faces (both male and female) start to reappear, Martha navigating the process of finding a place for herself amid this larger and more complicated social dynamic. She stays up late, eats pizza, smokes, hangs out, and puts on a shiny club outfit for a night out with her best friend Chillie (whose hair color gloriously wanders from dusty blonde to blue to purple and ultimately to soft pink across the subsequent years). Her attention is drawn by the boys, but the relationships with her girlfriends remain the centerweight of her life. And like all teenagers, her moods shift and her raw emotions flounce up and down continually, and Davey makes memorable images that capture these swings – from trying to act older and wondering if what she is doing is OK, to feeling isolated and alone and really having no patience for yet another up close picture. As hard as some of these moments are for Martha, Davey remains an authentic, honest, and most importantly, compassionate observer.

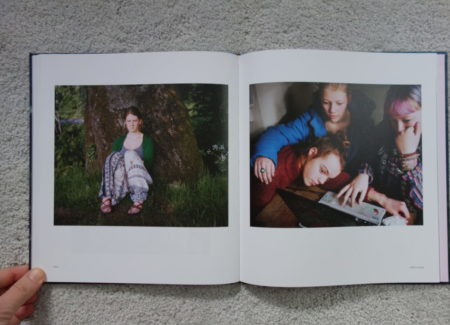

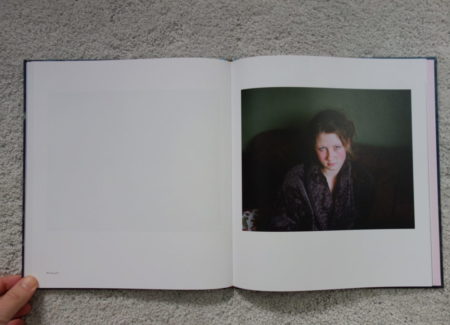

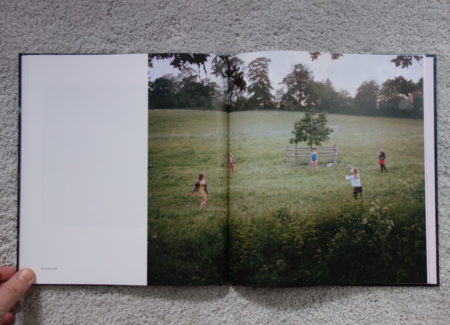

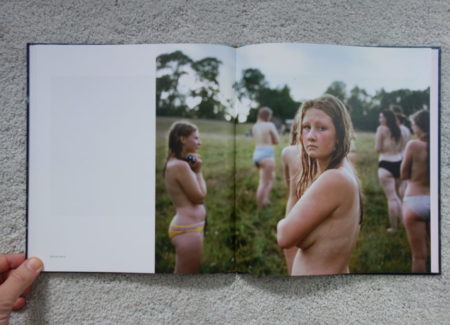

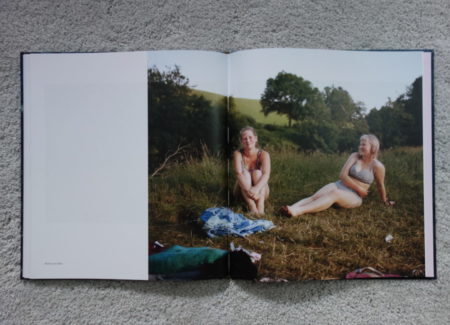

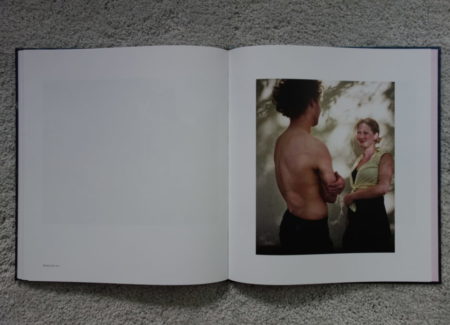

In the last third, a consolidation of sorts takes place, with the end of summer coinciding with a new and more roundly confident phase of Martha’s maturity. A frisbee is idly tossed with friends in an idyllic meadow and a lazy gathering of girls takes a topless swim in the cool water. As the light starts to fade on the day, Martha turns and looks back, and something seems to have changed – even though she’s wearing only her bikini bottoms, she seems indifferent to the whole scene, rather than awkward and self-conscious. This growing comfort with herself comes out in all of the last pictures in the series. She enjoys Chillie’s contagious laughter with genuine warmth, she touches others with gentleness and care, and she looks at her first boyfriend with a radiantly understated smile, seemingly happy with herself and ready to meet him on equal terms. But Davey doesn’t leave us with this broader sense of confident ease, she upends the mood with one final image of Martha with teary eyes just before leaving home, her eyes brimming with the close connection to family that she will now have to live without just a bit. It’s a smart choice, as it brings the intense cycle full circle, showing us just how much Martha now appreciates what she once found so unbearably uncomfortable. That look also powerfully acknowledges the shared bond with her stepmother, in a manner far more effective than words.

The understated design elements of Martha as a photobook help keep our attention on the photographs themselves. The images are generally given plenty of white space to breathe, and the rhythm and pace of their placement, along with a few larger images that span the gutter, is straightforward and unassuming. The book itself is intimate without being too small, and the cover image winds around to the back, like an embrace. Soft pink endpapers complete the feeling of being included in something personal.

Seen as a progression, Martha is rich in attentive emotional tenderness. As a father myself, I am amazed that Davey was able to capture so many of the fleeting and ephemeral states that her daughter went through during those short but transformative years. She thoughtfully shows us fragility and vulnerability, anticipation and apprehension, tension and anxiety, and ultimately a young woman who can navigate the choppy waters of social belonging, separation from family, and self definition. What parent could fail to be proud of the easy going confidence and layered human empathy Martha exhibits at the end? None of this growing up stuff is easy and Martha has clearly endured her share of heartaches and rough patches in coming to grips with the world around her. That she allowed us to travel along with her on this poignant journey, and that this well crafted photobook will endure as evidence of what occurred, is a gift indeed. Davey has delivered a durably vibrant and nuanced portrait of late adolescence here, one that I imagine will stand the test of time quite well.

Collector’s POV: Siân Davey is represented by Michael Hoppen Gallery in London (here). Davey’s work has little secondary market history, so gallery retail remains the best option for those collectors interested in following up.