JTF (just the facts): A total of 23 color photographs, framed in white and unmatted, and hung against white walls in a series of connected rooms on the main floor, and in the smaller double height space down the stairs. All of the works are UV cured pigment prints, made in 2020, 2023, and 2024. Physical sizes are roughly 29×25, 31×25, 32×25, 33×25, 33×44, 34×42, 34×51, 37×25, 41×50, 41×61, 41×65, 49×34, 51×34, 55×41, or 61×41, and all of the prints are available in editions of 5+2AP. (Installation shots below.)

Comments/Context: The first photograph presented in Roe Ethridge’s show of recent work is an understated stunner. Set against a deep green background, a man’s hand holds a striped garden hose with a purple, multi-function spray nozzle attached to the end; with just a tiny imperceptible squeeze of his hand, water begins to jet out from the nozzle, forming a ring-like shape of streams. Part standard commercial product shot and part Harold Edgerton stop motion magic, the image wrong footed (and enchanted) me from the get go, setting the tone for a show filled with Ethridge’s signature mixing and undermining of photographic aesthetics.

Given what seems to be a relatively constant drumbeat of commercial and editorial commissions to keep him busy, Ethridge has delivered half a dozen New York gallery shows of work in roughly the past decade (from 2023 (here), 2020 (here), 2019 (here), 2017 (here), 2014 (here), and 2011 (here)), not to mention additional appearances in group shows and art fairs and the publication of several photobooks. And consistently when I have run across an Ethridge photograph out in the wilds of the art world somewhere, more often than not my reaction has been “that’s another good one”; time and time again, almost without regard to his ostensible subject or project, Ethridge finds an elusive pressure point between obviousness and strangeness that gives his pictures a tension that is unlike anyone else’s. At his best, he’s a master at seemingly offering us a dull aesthetic that we think we recognize, only to subtly upend that overly easy visual assumption to give the composition some elegant static.

This show offers yet another grab bag of fresh imagery, mixing portraits, still lifes, and other arrangements into a gathering that doesn’t really coalesce into what we might normally call a coherent or integrated “body of work”. Instead, a turn through the gallery feels layered and wandering, with one photographic idea rubbing up against another with just enough randomness and friction to force us to ask questions about what exactly Ethridge is showing us.

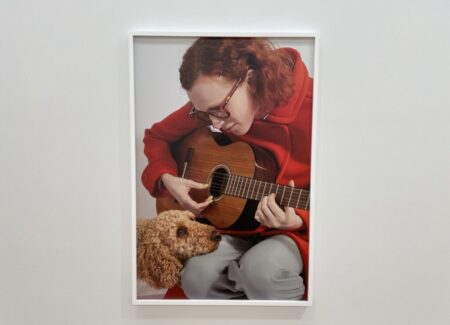

Many of Ethridge’s portraits have the look and feel of fashion, catalog, or commercial shoots, exaggerating fake realism into something that seems almost ridiculous when seen in an art gallery setting. The picture of smiling “Captain Irina” seems altogether like an advertisement, but her perfectly mannered posing with the captain’s hat is also quietly surreal and weirdly bright and chipper. “Karen and Bunnie” settles into a different vein of earnest oddness, with Karen strumming out a tune while Bunnie (the artist’s dog) listens attentively. “Lee Lou, Menemsha Beach” is a family picture of the artist’s daughter in a pink bucket hat, but it also might plausibly be an ad for a brand like J. Crew or Ralph Lauren. A portrait of the painter Anna Weyant leaning out of an upstairs window in Amagansett similarly oscillates between the possibility of a casual snapshot and the more likely reality of a staged commission artfully shot through the blur of a tree. And “This is Not a Cigarette” channels the disruptive intentions of René Magritte, via a smiling model holding a comically oversized cigarette. In each case, the portrait is mysteriously unstable – drifting and refusing to stay in one aesthetic lane.

Several of Ethridge’s new still lifes use ungrouted checkerboard tiles or a gingham tablecloth as backdrops. In years past, he overtly played with gridded motifs of pixels and pixelization, sometimes a bit blurred, and these works feel related to that earlier impulse, albeit with a less overt riffing on digital image culture. Here the ordered patterns provide backdrops for isolations of domesticity (red rubber gloves, a carton of red grapes, and a blue bicycle basket with a small snail inside), the pops of color contrasting with the monochrome patterns with unexpected energy.

More puzzling are a series of three images of glowing orbs nestled into floral greenery near Shore Front Parkway in Rockaway Beach (where Ethridge lives). Seen alternately in red, yellow, and blue, they echo other primary color series by artists across the history of art, but with an overtly staged, not quite real kitsch effect. Ethridge continues this line of thinking with an image of the nearby beach, with a rainbow dangling above the marching apartment blocks; the beach itself is a recreated work-in-progress, now decorated with a glorious natural glow.

Many of the rest of the images on view in this show actively play with the still life genre, creating odd mixes of objects that often somehow work together. There’s a sunflower still life staged with a bowl of tomatoes, but also with some rotting-looking gourds and an animal skull. There’s a gathering of a roughly cut pumpkin top, a ceramic dolphin, a glass orb, a piece of driftwood, a red golfball, and a framed photograph of Kate Bush. There are the lovely ranunculus blossoms that have been double bucketed, first in a plastic pitcher, and then in a copper pot. There are the zinnias hosted in a pizza sauce can with a peeling label, placed outside on an outcropping of rock. And there are the nested shells (with a nod Edward Weston) placed on the grey weathered boards of a dock. While some of these setups are likely populated with coded references, in most cases, the effect is simply an uneasy awkwardness that then settles into surprising comfort.

This show won’t be remembered as among Ethridge’s strongest or most innovative, but it still delivers flashes of credible interest here and there, when his conflict between the various intermingled and appropriated styles is most evident. As in Ethridge’s close up portrait of a dog (“Sprout”), he’s succeeded most when we’re left confused – is this an enlarged snapshot of a known dog or a family pet? is it a repurposed advertisement? is it a joke or a potential meme, like an Internet cat? What’s fascinating about such a simple picture is how Ethridge has encouraged us to read it in so many ways, intentionally placing it in an in-between zone where we never quite come to a conclusion.

Collector’s POV: The prints in this show are priced between $18000 and $28000, based on size. Ethridge’s work has become more available in the secondary markets in recent years, with prices ranging between roughly $2000 and $35000.