Phillips can certainly be pleased with the outcome of the Anthony Terrana single owner photographs sale. Interest was strong across all three price levels, the overall Buy-In rate hovered near 15%, and the Total Sale Proceeds nearly reached the High estimate, powered by a solid number of positive surprises.

Phillips can certainly be pleased with the outcome of the Anthony Terrana single owner photographs sale. Interest was strong across all three price levels, the overall Buy-In rate hovered near 15%, and the Total Sale Proceeds nearly reached the High estimate, powered by a solid number of positive surprises.

The summary statistics are below (all results include the buyer’s premium):

Total Lots: 165

Pre Sale Low Total Estimate: $3718500

Pre Sale High Total Estimate: $5400000

Total Lots Sold: 140

Total Lots Bought In: 25

Buy In %: 15.15%

Total Sale Proceeds: $5053750

Here is the breakdown (using the Low, Mid, and High definitions from the preview post, here):

Low Total Lots: 78

Low Sold: 72

Low Bought In: 6

Buy In %: 7.69%

Total Low Estimate: $533000

Total Low Sold: $677625

Mid Total Lots: 64

Mid Total Lots: 64

Mid Sold: 50

Mid Bought In: 14

Buy In %: 21.88%

Total Mid Estimate: $1452000

Total Mid Sold: $1348125

High Total Lots: 23

High Sold: 18

High Bought In: 5

Buy In %: 21.74%

Total High Estimate: $3415000

Total High Sold: $3028000

The top lot by High estimate was tied between lot 12, Alfred Stieglitz, Georgia O’Keeffe, 1919 (image at right, top, via Phillips), and lot 19, Irving Penn, Harlequin Dress (Lisa Fonssagrives-Penn), 1950, both estimated at $300000-500000. The Stieglitz sold for $302500 and the Penn sold for $290500. The top outcome of the sale was lot 28, Diane Arbus, Identical Twins Cathleen and Colleen, Roselle, NJ, 1967, estimated at $180000-220000, sold at $602500 (image at right, top, via Phillips).

92.14% of the lots that sold had proceeds in or above the estimate range. There were a total of 18 surprises in the sale (defined as having proceeds of at least double the high estimate):

Lot 3, Francesca Woodman, Untitled, Providence, Rhode Island, 1975-1978, estimated at $25000-35000, sold at $86500

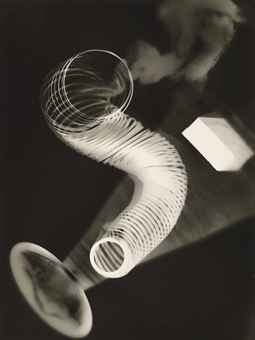

Lot 7, Laszlo Moholy-Nagy, Lyon Stadium, 1929. estimated at $90000-120000, sold at $278500

Lot 18, Herb Ritts, Versace Dress, Back View, El Mirage, 1990, estimated at $20000-30000, sold at $68500

Lot 20, Robert Polidori, Galerie Basse, Chateau de Versailles, 1985, estimated at $18000-22000, sold at $45000

Lot 28, Diane Arbus, Identical Twins Cathleen and Colleen, Roselle, NJ, 1967, estimated at $180000-220000, sold at $602500

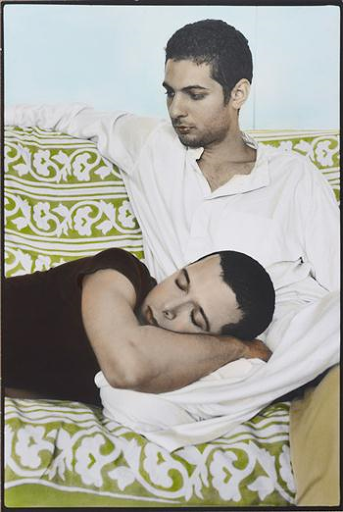

Lot 29, Angela Strassheim, Untitled (Father & Son), 2004, estimated at $10000-15000, sold at $35000

Lot 137, Pieter Hugo, Abdullahi Mohammed with Mainsara, Ogere-Remo, Nigeria, from Gadawan Kura, The Hyena Men II, 2007, estimated at $10000-15000, sold at $40000

Lot 41, Martine Franck, Children’s Library Built by the Atelier Montrouge, Clamart, France, 1965/later, estimated at $2000-3000, sold at $6875

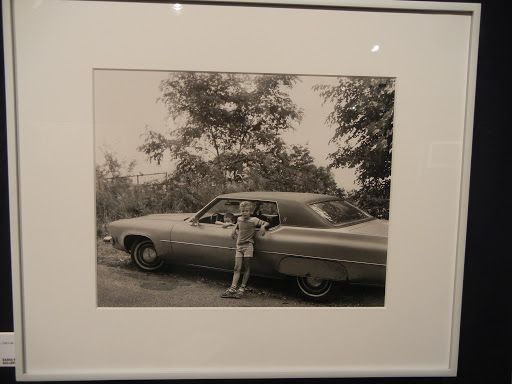

Lot 45, Lewis Hine, Tenement Product, Chicago, 1907/1920s, estimated at $6000-8000, sold at $52500 (image at right, middle, via Phillips)

Lot 67, Edward Steichen, The Flatiron Evening, 1905, estimated at $5000-7000, sold at $23750

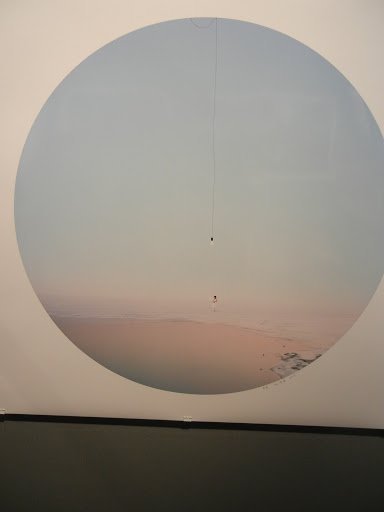

Lot 98, Masao Yamamoto, Selected images from A Box of Ku and Nakazora, 1990-2002, estimated at $6000-8000, sold at $18750

Lot 101, Lynn Davis, Red Pyramid, Dashur, Cairo, Egypt, 1997, estimated at $7000-9000, sold at $20000

Lot 108, Nobuyoshi Araki, Untitled, 1990-2000, estimated at $3000-4000, sold at $11250

Lot 114, Sally Mann, Untitled from Deep South, 1998, estimated at $7000-9000, sold at $26250

Lot 130, Ryan McGinley, Whirlwind, 2003, estimated at $5000-7000, sold at $15000

Lot 140, Mickalene Thomas, Afro Goddess Lover’s Friend, 2006, estimated at $8000-10000, sold at $23750

Lot 158, Alex Prager, Annie, 2007, estimated at $5000-7000, sold at $30000 (image at right, bottom, via Phillips)

Lot 159, Alex Prager, Wendy from Week-End, 2009, estimated at $7000-9000, sold at $21875

Complete lot by lot results can be found here.

Phillips

450 Park Avenue

New York, NY 10022

Phillips’ Under the Influence sale tomorrow in London has a selection of mid range photographs worth a quick look. Overall, there are a total of 41 lots of photography available in the sale, with a Total High Estimate for photography of £318000.

Phillips’ Under the Influence sale tomorrow in London has a selection of mid range photographs worth a quick look. Overall, there are a total of 41 lots of photography available in the sale, with a Total High Estimate for photography of £318000. Total High Lots (high estimate above £25000): 0

Total High Lots (high estimate above £25000): 0