Paul McDonough: Sight Seeing @Sasha Wolf

JTF (just the facts): A total of 18 black and white photographs, framed in black and matted, and hung in the long single room gallery space. All of the prints are modern gelatin silver prints, made from negatives taken between 1971 and 1982. The prints are sized 16×20 and come in editions of 15. (Installation shots at right.)

JTF (just the facts): A total of 18 black and white photographs, framed in black and matted, and hung in the long single room gallery space. All of the prints are modern gelatin silver prints, made from negatives taken between 1971 and 1982. The prints are sized 16×20 and come in editions of 15. (Installation shots at right.)

Comments/Context: When we think of 1970s West coast photography, Paul McDonough isn’t a name that we might normally come up with right away. But the New York photographer spent time in California and Oregon during that fertile period, making outsider pictures that combine his street-savvy awareness for the serendipity of converging people with the easy going, laid back warmth of life out West. They’re street photographs, only in this case, the street is a beach, a sun-baked parking lot, or a paved boardwalk.

McDonough’s image of the swirling mass of bodies around a Santa Monica beach camper is the kind of complex composition that has its roots in New York city chaos. Swimsuited men and women perch on top of the RV, stand in the doorway, climb on the back, catch rays nearby, and generally wander around, a half dozen mini-vignettes and tiny gestures captured in one single all-over frame. Other photographs zero in on knots and tangles of young people, hanging around cars and checking each other out, the indirect interactions of guys and girls falling into time worn patterns of looking and not looking. But the crisply observed local details are what creates the atmosphere: short shorts, plaid bell bottoms, beater convertibles, rusty El Caminos, bikinis, old school roller skates, wavy, sun-bleached Farrah Fawcett hair, and warm afternoon light. Again and again, McDonough’s timing is quietly and casually perfect: a blown chewing gum bubble underneath a spraying fountain, a escalating line up of children on the ladder of a playground slide, and the separation of skateboarders on a gas station blacktop all coalesce at exactly the right moment. He has captured a relaxed world where pulling your car right up on the beach isn’t out of the ordinary and where sunbathing on a grocery store curb amid the abandoned shopping carts seems entirely natural, and he makes it look so effortless that we might think taking these kind of pictures is somehow easy, which of course, it’s not.

McDonough’s image of the swirling mass of bodies around a Santa Monica beach camper is the kind of complex composition that has its roots in New York city chaos. Swimsuited men and women perch on top of the RV, stand in the doorway, climb on the back, catch rays nearby, and generally wander around, a half dozen mini-vignettes and tiny gestures captured in one single all-over frame. Other photographs zero in on knots and tangles of young people, hanging around cars and checking each other out, the indirect interactions of guys and girls falling into time worn patterns of looking and not looking. But the crisply observed local details are what creates the atmosphere: short shorts, plaid bell bottoms, beater convertibles, rusty El Caminos, bikinis, old school roller skates, wavy, sun-bleached Farrah Fawcett hair, and warm afternoon light. Again and again, McDonough’s timing is quietly and casually perfect: a blown chewing gum bubble underneath a spraying fountain, a escalating line up of children on the ladder of a playground slide, and the separation of skateboarders on a gas station blacktop all coalesce at exactly the right moment. He has captured a relaxed world where pulling your car right up on the beach isn’t out of the ordinary and where sunbathing on a grocery store curb amid the abandoned shopping carts seems entirely natural, and he makes it look so effortless that we might think taking these kind of pictures is somehow easy, which of course, it’s not.

All in, this show broadens our view of McDonough, exposing a side of his work that we hadn’t seen before. Step by step, exhibit by exhibit, we’re working our way forward in time, his archive proving richer and more varied with every successive discovery.

All in, this show broadens our view of McDonough, exposing a side of his work that we hadn’t seen before. Step by step, exhibit by exhibit, we’re working our way forward in time, his archive proving richer and more varied with every successive discovery.

Collector’s POV: The works on view are priced at $3000 each. McDonough’s work has very little secondary market history, so gallery retail is likely the best/only option for those collectors interested in following up.

Ryan McGinley @High Line

Sally Gall @Julie Saul

Erwin Olaf @Hasted Kraeutler

Gordon Matta-Clark, Above and Below @David Zwirner

JTF (just the facts): A total of 10 photographic works, 26 pencil/ink drawings, 4 films, and 1 sculpture, variously framed and matted, and hung/shown against white walls in the large, two room divided space. Counting the photographs is a bit tricky as many have multiple images printed together as a single work, or come in groups that make up a single work. There are 6 works that are printed on a single sheet, 1 diptych, 1 triptych, 1 set of 4 images, and 1 set of 6 images. All of the photographic prints are either chromogenic prints, silver dye bleach prints, or gelatin silver prints, taken between 1974 and 1977. Individual sizes range from 36×27 to 92×20, with many at 40×30 (or reverse); edition sizes are generally 3, when noted. (Installation shots at right.)

JTF (just the facts): A total of 10 photographic works, 26 pencil/ink drawings, 4 films, and 1 sculpture, variously framed and matted, and hung/shown against white walls in the large, two room divided space. Counting the photographs is a bit tricky as many have multiple images printed together as a single work, or come in groups that make up a single work. There are 6 works that are printed on a single sheet, 1 diptych, 1 triptych, 1 set of 4 images, and 1 set of 6 images. All of the photographic prints are either chromogenic prints, silver dye bleach prints, or gelatin silver prints, taken between 1974 and 1977. Individual sizes range from 36×27 to 92×20, with many at 40×30 (or reverse); edition sizes are generally 3, when noted. (Installation shots at right.)

Comments/Context: This smart show chronicles the late works of Gordon Matta-Clark, documenting each separate project via a combination of films, photographs, drawings, and other ephemera. The different mediums show us alternate sides of Matta-Clark’s artistic thinking, from his whimsical and imaginative preliminary drawings to collaged multi-perspective photographs showing particular angles and views of his in-process and completed architectural interventions. His films layer in a sense of time and motion, of open-ended exploration and discovery rather than predetermined creation. Taken together, there is a richness of context here that brings the projects alive.

Photographically, Matta-Clark’s works start as straightforward documentation of cut-throughs, holes, and multiple levels of demolished walls and construction debris, with an eye for the iterations and changes that came with each successive removal. The images are then collaged together, mixing sizes and vantage points to create a kind of spatial rhythm, moving outward through a conical oculus or downward through descending squares, often with an unexpected see-through vista. The pictures feature interlocking arced geometries that become more complex and abstract when seen from specific spots, the larger logic of his precise interventions finally coming into view when surrounded by smaller strips of contact sheet style pictures.

Photographically, Matta-Clark’s works start as straightforward documentation of cut-throughs, holes, and multiple levels of demolished walls and construction debris, with an eye for the iterations and changes that came with each successive removal. The images are then collaged together, mixing sizes and vantage points to create a kind of spatial rhythm, moving outward through a conical oculus or downward through descending squares, often with an unexpected see-through vista. The pictures feature interlocking arced geometries that become more complex and abstract when seen from specific spots, the larger logic of his precise interventions finally coming into view when surrounded by smaller strips of contact sheet style pictures.

A second group of works play with vertical descent, moving from the street down through successive layers of tunnels and understructures, stairs and sub-basements. Laid out as stacks of images, the works provide a kind of visual core sample, diving down from a landmark like the Opera in Paris to the subterranean catacombs and forgotten caverns below. Two films capture these performance-like explorations, one in Paris and one in New York, following subways, sewer systems, and other dark, murky pathways underneath the two cities. This verticality takes a different form in Matta-Clark’s film City Slivers, where city traffic and urban architecture are cut into thin strips, moving and changing within the confines of the narrow band of vision. It’s a jittery, tight view of New York, full of cuts, reflections, and cramped tallness.

A second group of works play with vertical descent, moving from the street down through successive layers of tunnels and understructures, stairs and sub-basements. Laid out as stacks of images, the works provide a kind of visual core sample, diving down from a landmark like the Opera in Paris to the subterranean catacombs and forgotten caverns below. Two films capture these performance-like explorations, one in Paris and one in New York, following subways, sewer systems, and other dark, murky pathways underneath the two cities. This verticality takes a different form in Matta-Clark’s film City Slivers, where city traffic and urban architecture are cut into thin strips, moving and changing within the confines of the narrow band of vision. It’s a jittery, tight view of New York, full of cuts, reflections, and cramped tallness.

I certainly came away from this exhibit with a deeper sense for Matta-Clark’s sophisticated visualization talents. The gathered works point to seeing built environments with a strong sense for their underlying structure, to getting beyond the superficial and manipulating the patterns underneath to get at the purity of their abstract geometries. The mix of brainy conceptual thinking and rough and ready physicality keeps the projects from becoming too clever; the dust and rubble adds a layer of authenticity to his crisp rationality. His eyes slash through walls and floors like lasers, seeing a elegance of form hiding within, waiting to be released.

I certainly came away from this exhibit with a deeper sense for Matta-Clark’s sophisticated visualization talents. The gathered works point to seeing built environments with a strong sense for their underlying structure, to getting beyond the superficial and manipulating the patterns underneath to get at the purity of their abstract geometries. The mix of brainy conceptual thinking and rough and ready physicality keeps the projects from becoming too clever; the dust and rubble adds a layer of authenticity to his crisp rationality. His eyes slash through walls and floors like lasers, seeing a elegance of form hiding within, waiting to be released.

Collector’s POV: The photographic works in this show are priced between $150000 and $1500000 (the set of 6 images). Matta-Clark’s works have not come up at auction with any regularity I recent years; prices have ranged between roughly $7000 and $115000, but this range may not be entirely representative of the market for his most sought after works.

Auction Preview: Fine Photographs & Photobooks, April 18, 2013 @Swann

Later this week, Swann brings to market a combo photographs and photobooks auction, with the books mixed into the flow of the sale rather than pulled out at the end. The material is heavily weighted toward the lower end of the price range, with Swann’s usual mix of vernacular, vintage, and modern prints. Overall, there are 301 lots available, with a total High estimate of $1884050.

Later this week, Swann brings to market a combo photographs and photobooks auction, with the books mixed into the flow of the sale rather than pulled out at the end. The material is heavily weighted toward the lower end of the price range, with Swann’s usual mix of vernacular, vintage, and modern prints. Overall, there are 301 lots available, with a total High estimate of $1884050.

Here’s the statistical breakdown:

Total Low Lots (high estimate up to and including $10000): 269

Total Low Estimate (sum of high estimates of Low lots): $1260050

Total Mid Lots (high estimate between $10000 and $50000): 32

Total Mid Estimate: $624000

Total High Lots (high estimate above $50000): 0

Total High Estimate: NA

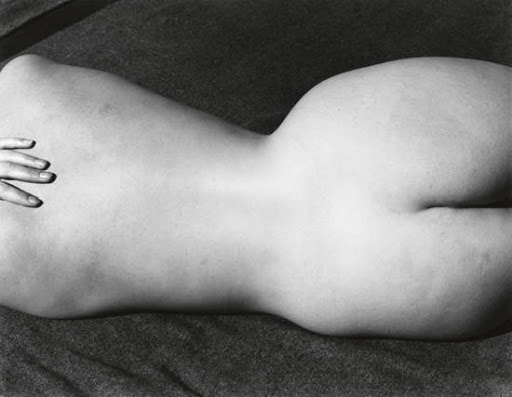

The top lot by High estimate is tied between two lots: lot 24, Southworth & Hawes, Daguerreotype of blue-eyed woman, c1850 (image at right, middle), estimated at $30000-45000, and lot 79, Edward Weston, Charis (nude), 1935 (image at right, top), estimated at $35000-45000.

The top lot by High estimate is tied between two lots: lot 24, Southworth & Hawes, Daguerreotype of blue-eyed woman, c1850 (image at right, middle), estimated at $30000-45000, and lot 79, Edward Weston, Charis (nude), 1935 (image at right, top), estimated at $35000-45000.

The following is the list of photographers with 5 or more lots in the sale (with the number of lots in parentheses):

Ansel Adams (14 )

Andre Kertesz (10)

Henri Cartier-Bresson (7)

Walker Evans (7)

Manuel Alvarez Bravo (5)

Harry Callahan (5)

Alfred Eisenstaedt (5)

O. Winston Link (5)

Minor White (5)

Other works of interest include lot 104, Aubrey Bodine, Curving Steps, 1943, estimated at $4000-6000 (image at right, bottom; all images via Swann).

The complete lot by lot catalog can be found here.

Fine Photographs & Photobooks

April 18th

Swann Auction Galleries

104 East 25th Street

New York, NY 10010

Auction Results: Under the Influence, April 11, 2013 @Phillips London

It was a pretty dismal outcome for the photography included in Phillips’ Under the Influence sale in London last week. With a Buy-In rate for photography topping 60% and no positive surprises, it is no surprise that the Total Sale Proceeds for photography missed the low end of the estimate range by a meaningful margin.

The summary statistics are below (all results include the buyer’s premium):

Total Lots: 41

Pre Sale Low Total Estimate: £221000

Pre Sale High Total Estimate: £318000

Total Lots Sold: 16

Total Lots Bought In: 25

Buy In %: 60.98%

Total Sale Proceeds: £116063

Here is the breakdown (using the Low, Mid, and High definitions from the preview post, here):

Low Total Lots: 11

Low Sold: 4

Low Bought In: 7

Buy In %: 63.64%

Total Low Estimate: £51000

Total Low Sold: £14000

Mid Total Lots: 30

Mid Sold: 12

Mid Bought In: 18

Buy In %: 60.00%

Total Mid Estimate: £267000

Total Mid Sold: £102063

High Total Lots: 0

High Sold: NA

High Bought In: NA

Buy In %: NA

Total High Estimate: £0

Total High Sold: NA

The top photography lot by High estimate was lot 122, Jitish Kallat, Cenotaph (A Deed of Transfer), 2007, at £18000-25000; it was also the top photography outcome of the sale at £20000.

81.25% of the lots that sold had proceeds above or in the estimate range, but that statistic is a little misleading, since only 3 photography lots sold above the range and there were no positive surprises (defined as having proceeds of at least double the high estimate).

Complete lot by lot results can be found here

Phillips

Howick Place

London SW1P 1BB

Chuck Kelton & Eric William Carroll, New Photogenic Drawings @Bosi Contemporary

JTF (just the facts): A paired show consisting of the work of two photographers, Chuck Kelton and Eric William Carroll, shown against white walls in a large, single room gallery space. There are 11 photographs by Kelton on view, all unique hand toned gelatin silver prints. The works are framed in black and unmatted, sized 19×23, and were made in 2012. A folio of 9 smaller prints (each roughly 8×10) from the same series is shown on a table in the center of the gallery. There are four works by Carroll on view in the back half of the space, each a set of 3 or 4 diazotype prints hung together. The works are unframed and pinned directly to the wall. Each individual panel is sized 72×36, and the works were made in 2010. An artist book from the same series is shown on the table in the center of the gallery. The exhibit was curated by Alison Bradley. (Installation shots at right.)

JTF (just the facts): A paired show consisting of the work of two photographers, Chuck Kelton and Eric William Carroll, shown against white walls in a large, single room gallery space. There are 11 photographs by Kelton on view, all unique hand toned gelatin silver prints. The works are framed in black and unmatted, sized 19×23, and were made in 2012. A folio of 9 smaller prints (each roughly 8×10) from the same series is shown on a table in the center of the gallery. There are four works by Carroll on view in the back half of the space, each a set of 3 or 4 diazotype prints hung together. The works are unframed and pinned directly to the wall. Each individual panel is sized 72×36, and the works were made in 2010. An artist book from the same series is shown on the table in the center of the gallery. The exhibit was curated by Alison Bradley. (Installation shots at right.)

At first glance, Chuck Kelton’s photograms are deceptive and uncertain. From afar, the black craggy areas at the bottom look like mountains or mesas captured as sharp silhouettes. Up close, they reverse into top down topographical maps of unknown shorelines and continental edges, every inlet and bay shown in exacting detail. The “sky” part of each image is decorated with wisps of smoke, murky clouds, or indistinct washes and apparitions (depending on your perspective), and each background is subtly toned in shifting hues, giving the appearance of sunrise or sunset, or some transitional nether time between dark and light. Put together, the works have the style of landscapes, but remain open for imaginative interpretation, full of unspoken foreboding.

At first glance, Chuck Kelton’s photograms are deceptive and uncertain. From afar, the black craggy areas at the bottom look like mountains or mesas captured as sharp silhouettes. Up close, they reverse into top down topographical maps of unknown shorelines and continental edges, every inlet and bay shown in exacting detail. The “sky” part of each image is decorated with wisps of smoke, murky clouds, or indistinct washes and apparitions (depending on your perspective), and each background is subtly toned in shifting hues, giving the appearance of sunrise or sunset, or some transitional nether time between dark and light. Put together, the works have the style of landscapes, but remain open for imaginative interpretation, full of unspoken foreboding. Using the diazotype (blueprint) process, Eric William Carroll’s images of forest undergrowth are more easily recognizable, capturing filtered light and dark shadows in a haze of soft, royal blue. Tiny up-close leaves are silhouetted against bright spots in the dense woods, while the background recedes into a mottled blur. Standing in their presence (and they have a definite physicality given their size), I saw visual echoes of Robert Adams’ recent work, the River Taw photograms of Susan Derges, and even classical nature screens from China and Japan. Their Yves Klein color is rich and tactile, the effect a mixture of bright energy and muted meditation.

Using the diazotype (blueprint) process, Eric William Carroll’s images of forest undergrowth are more easily recognizable, capturing filtered light and dark shadows in a haze of soft, royal blue. Tiny up-close leaves are silhouetted against bright spots in the dense woods, while the background recedes into a mottled blur. Standing in their presence (and they have a definite physicality given their size), I saw visual echoes of Robert Adams’ recent work, the River Taw photograms of Susan Derges, and even classical nature screens from China and Japan. Their Yves Klein color is rich and tactile, the effect a mixture of bright energy and muted meditation.Mikhail Baryshnikov @Mark Morris Dance Center

Thomas Ruff: photograms and ma.r.s. @David Zwirner: A Review Conversation with Richard B. Woodward

JTF (just the facts): A total of 22 large scale color photographs, framed in black and unmatted, and hung in two pairs of large divided rooms and two smaller transitional spaces. All of the works are chromogenic prints, made between 2010 and 2013. The photograms are sized 95×73 and are available in editions of 4. The images from the ma.r.s. series (including the 3D images) are sized 100×73 and are available in editions of 3. A small selection of vintage work can be found in a side gallery. (Installation shots at right.)

JTF (just the facts): A total of 22 large scale color photographs, framed in black and unmatted, and hung in two pairs of large divided rooms and two smaller transitional spaces. All of the works are chromogenic prints, made between 2010 and 2013. The photograms are sized 95×73 and are available in editions of 4. The images from the ma.r.s. series (including the 3D images) are sized 100×73 and are available in editions of 3. A small selection of vintage work can be found in a side gallery. (Installation shots at right.)

What I think is fascinating is that Ruff has found a way to stay observant of the traditions of the genre while at the same time exploding its previous boundaries. Looking up at his massive works (and you have to look up given their scale), I could still see the remnants of Schad, Moholy-Nagy, and Man Ray, but their foundation ideas have been transformed into something modern and machined. Enlarged to roughly 8 by 6 feet, typical photogram ovals, swirls, and silhouettes take on different characteristics, the intimacy of hand-crafted darkroom experimentation and simple chance traded for bold, expansive gestures and increased compositional complexity. They’re truly immersive in a way utterly different than photograms have ever been before.

What I think is fascinating is that Ruff has found a way to stay observant of the traditions of the genre while at the same time exploding its previous boundaries. Looking up at his massive works (and you have to look up given their scale), I could still see the remnants of Schad, Moholy-Nagy, and Man Ray, but their foundation ideas have been transformed into something modern and machined. Enlarged to roughly 8 by 6 feet, typical photogram ovals, swirls, and silhouettes take on different characteristics, the intimacy of hand-crafted darkroom experimentation and simple chance traded for bold, expansive gestures and increased compositional complexity. They’re truly immersive in a way utterly different than photograms have ever been before. Ruff isn’t making one-offs. They’re not unique photographs. His software does the work and when it produces a set of whirling shapes he likes, he stops the process and prints as many as he (or his dealer) wants. He’s using his computer as an optical printer, the way many filmmakers and videographers have done before him. The associations created by the unexpected collisions in a great Man Ray were often funny. Ruff’s “photograms” lack a sense of humor, and the chaos he harnesses is safer for being entirely virtual and situated in the realm of mathematical algorithms, not those of a three-dimensional world of objects acted upon by time and gravity.

Ruff isn’t making one-offs. They’re not unique photographs. His software does the work and when it produces a set of whirling shapes he likes, he stops the process and prints as many as he (or his dealer) wants. He’s using his computer as an optical printer, the way many filmmakers and videographers have done before him. The associations created by the unexpected collisions in a great Man Ray were often funny. Ruff’s “photograms” lack a sense of humor, and the chaos he harnesses is safer for being entirely virtual and situated in the realm of mathematical algorithms, not those of a three-dimensional world of objects acted upon by time and gravity. Let’s move on to the Mars landscapes. I use the word landscape with some hesitation, as I still haven’t exactly come to grips with the fuzzy line between fact and fiction Ruff is walking in these pictures. While he has begun with authentic NASA footage, his cropping, compressing, and coloration move the final results pretty far away from documentation in my mind. It reminds me of a discussion I was having with another writer who was troubled by Michael Benson’s recent space images, mostly because it seemed like they were too close to the scientific “truth” and that his original artistic input was less visible. In this case, I think it is clear that Ruff has used the Mars images as raw material for his own flights of fancy, and that we shouldn’t be confused about being somewhere “real”. That said, the windblown dunes, the tactile crater pocked expanses, and the sandy eroded washes are undeniably texturally seductive.

Let’s move on to the Mars landscapes. I use the word landscape with some hesitation, as I still haven’t exactly come to grips with the fuzzy line between fact and fiction Ruff is walking in these pictures. While he has begun with authentic NASA footage, his cropping, compressing, and coloration move the final results pretty far away from documentation in my mind. It reminds me of a discussion I was having with another writer who was troubled by Michael Benson’s recent space images, mostly because it seemed like they were too close to the scientific “truth” and that his original artistic input was less visible. In this case, I think it is clear that Ruff has used the Mars images as raw material for his own flights of fancy, and that we shouldn’t be confused about being somewhere “real”. That said, the windblown dunes, the tactile crater pocked expanses, and the sandy eroded washes are undeniably texturally seductive. Unlike the photograms, there are solid, if ghostly, referents here that his own artistic interpretations can play against. I saw the works as not only commenting on the new worlds we are exploring with cameras attached to wheeled and tractor vehicles and orbiting telescopes but a wry salute to the Internet itself, as a place where objects float around without boundaries and swim into our view without our having much control, like the objects that appear in the night sky.

Unlike the photograms, there are solid, if ghostly, referents here that his own artistic interpretations can play against. I saw the works as not only commenting on the new worlds we are exploring with cameras attached to wheeled and tractor vehicles and orbiting telescopes but a wry salute to the Internet itself, as a place where objects float around without boundaries and swim into our view without our having much control, like the objects that appear in the night sky. Since we haven’t touched on them yet, I think a few words are in order on the 3D images. For me, these were the weakest works on view, mostly because they seemed the most literal and obvious, even though we haven’t seen many photographers embrace the technology yet. I won’t dispute that there is a gee whiz factor at work when seeing these vertiginous Martian craters and spires (get up close and it feels like you’re really falling in), but I worry that their power to surprise us will be severely diminished in a decade or two. They don’t seem as inherently smart as the others, but I appreciate that Ruff is taking risks with the new tools and trying to figure out what they can and can’t do. The images seem a little more like a work in progress, a necessary intermediate step, or a set of ideas that haven’t yet converged exactly, a little like the first round of candy colored space images (Cassini) that now seem like a preface to the Mars work. And who, by the way, keeps 3D glasses handy for home viewing? Without them, the 3D prints are a headache inducing blur.

Since we haven’t touched on them yet, I think a few words are in order on the 3D images. For me, these were the weakest works on view, mostly because they seemed the most literal and obvious, even though we haven’t seen many photographers embrace the technology yet. I won’t dispute that there is a gee whiz factor at work when seeing these vertiginous Martian craters and spires (get up close and it feels like you’re really falling in), but I worry that their power to surprise us will be severely diminished in a decade or two. They don’t seem as inherently smart as the others, but I appreciate that Ruff is taking risks with the new tools and trying to figure out what they can and can’t do. The images seem a little more like a work in progress, a necessary intermediate step, or a set of ideas that haven’t yet converged exactly, a little like the first round of candy colored space images (Cassini) that now seem like a preface to the Mars work. And who, by the way, keeps 3D glasses handy for home viewing? Without them, the 3D prints are a headache inducing blur. DLK: In general, I think my overall takeaway from this show is more positive than yours. I walked out of the gallery convinced that Ruff continues to be one of the most compelling and challenging artists working in contemporary photography, and one that we ignore at our peril. Even if I might quibble with the durability of some of his end results, the behind–the-scenes thinking that has gone into his projects is consistently smart and perceptive. His view point continues to evolve as he plays through different sourced imagery variations, getting more complex and nuanced as he dives deeper. More than many of his well-known contemporaries, he’s always testing limits, enlarging our understanding of the medium. Yes, he’s brainy, and brilliant, and sometimes inscrutably obtuse, but that’s what makes his work so important.

DLK: In general, I think my overall takeaway from this show is more positive than yours. I walked out of the gallery convinced that Ruff continues to be one of the most compelling and challenging artists working in contemporary photography, and one that we ignore at our peril. Even if I might quibble with the durability of some of his end results, the behind–the-scenes thinking that has gone into his projects is consistently smart and perceptive. His view point continues to evolve as he plays through different sourced imagery variations, getting more complex and nuanced as he dives deeper. More than many of his well-known contemporaries, he’s always testing limits, enlarging our understanding of the medium. Yes, he’s brainy, and brilliant, and sometimes inscrutably obtuse, but that’s what makes his work so important.2013 Guggenheim Fellows in Photography

Here’s the short list of this year’s Guggenheim Fellowship winners in Photography, found in a full page ad in this morning’s New York Times. The entire list of current fellows can be found on the foundation website (here). Lots of familiar names this year.

CREATIVE ARTS

Photography

Scott Conarroe (here)

Bruce Gilden (here)

Sharon Harper (here)

Michael Kolster (here)

Deana Lawson (here)

Deborah Luster (here)

Christian Patterson (here)

Gary Schneider (here)

Mike Sinclair (here)

Alec Soth (here)

Valerio Spada (here)

HUMANITIES

Photography Studies

Michael Lesy (here)