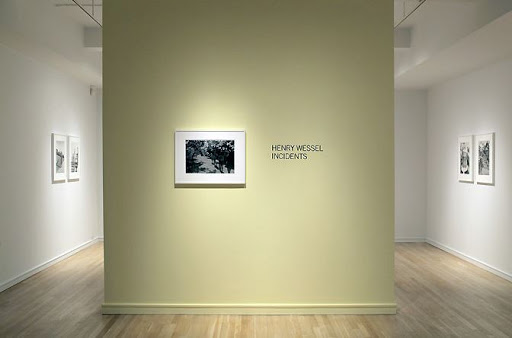

In just two short years, Frieze has quickly become the gold standard for art fairs in New York. Its soaring white tent offers the best visitor experience by far, with an abundance of bright airy light and wider aisles that lessen the feeling of being cramped into an endless rabbit warren. While too much time in any fair can generate sensory fatigue, a wandering amble through the booths at Frieze is about as good as it gets for all-in-one smorgasbord fair going.

Photography-wise, Frieze offers an almost perfect foil to the AIPAD photography fair. While there isn’t a single photography specialist booth on the map here, photographs are on display in abundance, with work on view from the top contemporary art galleries and lesser known venues from all over the world. For those interested in photography, Frieze becomes like a kind of treasure hunt, where each booth needs to be scoured for photographs that might be hiding somewhere. Since the photographs are not isolated out in a special section, they are seen in the messy, chaotic context of everything else that is going on in contemporary art, which provides some refreshing juxtapositions and unexpected visual connections. It’s an energetic, exciting slice of the medium.

This report is divided into five sections of image highlights. I have consciously avoided selecting works that have recently been on view in New York gallery shows or that I have already reviewed in another context, instead opting for fresh images new to the market or surprising finds from the past. Gallery names/links are followed by the artist/photographer name, the price of the work (in a dizzying array of currencies), and some notes and comments as appropriate. The booths are organized in my path through the fair, beginning at the South entrance.

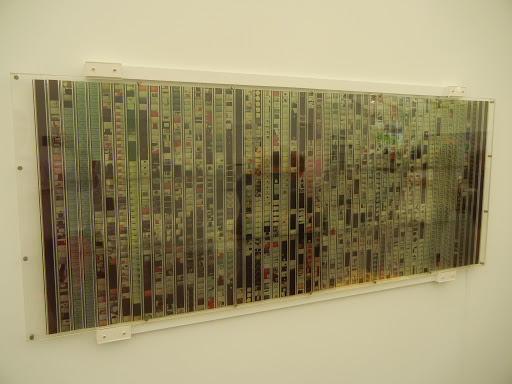

GB Agency (here): Robert Breer, $91500. This work was made up of Kodachrome film strips laid between sheets of Plexiglas. It’s a jittering, almost blinking, series of fragments of Breer’s paintings.

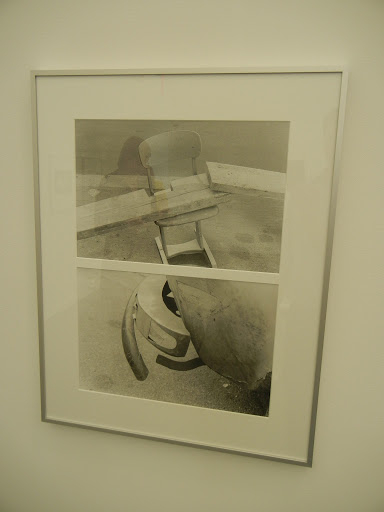

Freymond-Guth Fine Arts (here): Stefan Burger, $4500. Sculptural still life assemblages, with an echo of Elad Lassry’s matchy-matchy colors and frames.

Victoria Miro (here): Alex Hartley, $30000. A diptych of rocky cave dwellings, with the surface of the print built up and carved out to provide selected areas of hand-crafted three dimensionality.

Galeria Fortes Vilaça (here): Mauro Restiffe, $2700. A layered geometric composition of wood inlay, wall molding, and linear white pipes.

303 Gallery (here): Collier Schorr, $26000. New work by Schorr, and no, I haven’t mistakenly rotated the image – it’s intensely vertical, almost like a crucifixion.

Galerie Mezzanin (here): Gerald Domenig, $7000. Conceptual exercises in formal balance and unexpected optical illusion.

Lisson Gallery (here): Richard Wentworth, £5500. A complex combination of found textures from his series of Occasional Geometries. Notice the print has been nailed to the supporting board (underneath a deep custom wood frame), giving it a more physical presence.

Galerie Martin Janda (here): Alessandro Balteo Yazbeck, $10500. A scanned book image, with areas of angled distortion and pixelized colored squares. This was the only piece of glitch photography I saw in the entire fair, which was a bit of a surprise.

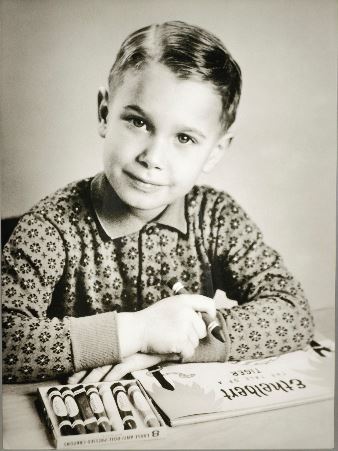

David Zwirner (here): Thomas Ruff, $2800 each (open editions). This booth was a solo sampler of Thomas Ruff, with mini rooms of the new photograms and blurred nudes, and selected works from other parts of his career (substrat, mars, interiors, large portraits, etc.) hung on side walls. I continue to find his early 1980s portraits to be among his best work.

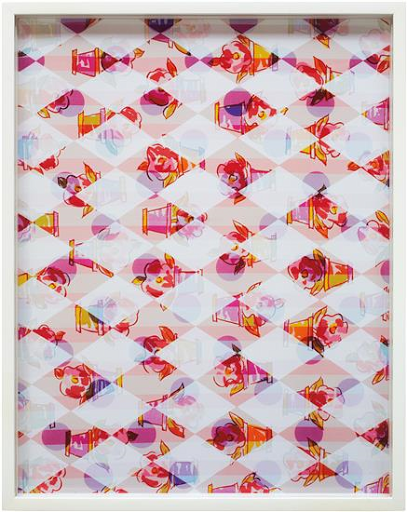

Alison Jacques Gallery (here): Birgit Jürgenssen, $60000. Feminist social critique with an edge of almost Surreal dark humor.

Continue to Part 2 here.