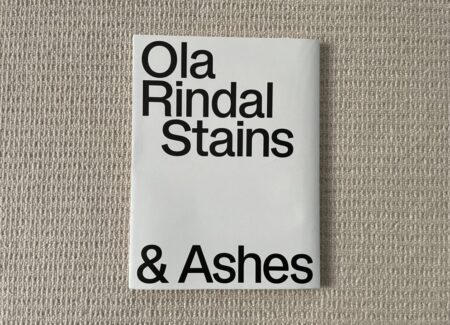

JTF (just the facts): Published in 2025 by Poursuite Editions (here). Softcover, 24×32 cm, 160 Japanese-bound pages, with 75 black-and-white photographs. There are no texts or essays included. Design by Spassky Fischer. (Cover and spread shots below.)

Comments/Context: Crisp precision is so much a part of the mechanistic aesthetic of photography that we generally take it for granted. When looking at a photograph, we expect that it will be sharp, clear, and exacting, and that it will offer us a faithful representation of its subject. So when photographs don’t behave this way, when they are deliberately blurred, flared, fogged, or uncertain in some way, they create friction with our expectations and force us to look again more closely.

This was my initial experience with Ola Rindal’s Stain & Ashes – it caught me off guard, and as the pages turned, it felt more and more unexpected and mysterious, and I wanted to understand it better. Who makes an entire photobook filled with ghostly images of found stains, blurred figures, fogged landscapes, and other even less identifiable tactile presences? And to what end?

Rindal is a Norwegian photographer currently living in Paris, who has been mixing commercial and commissioned work with personal projects for nearly two decades, with many of his efforts ultimately taking shape as photobooks made with a range of publishers from around the world. Rindal did his artistic training at Gothenburg University in the late 1990s, and since then, he seems to have been pushing himself to thoughtfully unlearn what he was taught, his projects continually testing the boundaries of how photographs function, so they can better capture the fleeting poetry of everyday life.

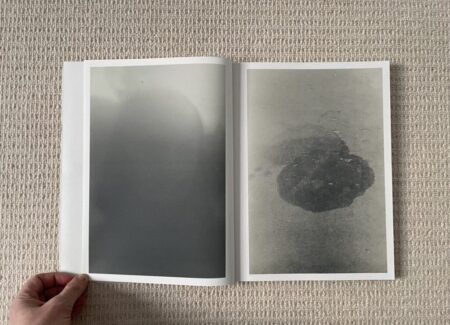

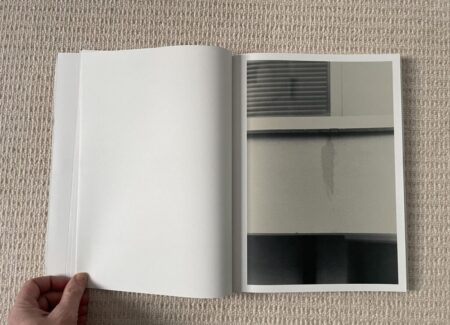

Stains & Ashes is a decently large book, with image reproductions that generally fill the folded pages to thin white borders, the palette of the entire photobook shifted slightly toward warmer tones of middle grey in the larger spectrum of monochrome black and white. The overall feel is muted and contemplative, almost hushed, creating a whispered sense of perplexing elusiveness that wants to be unraveled and explored.

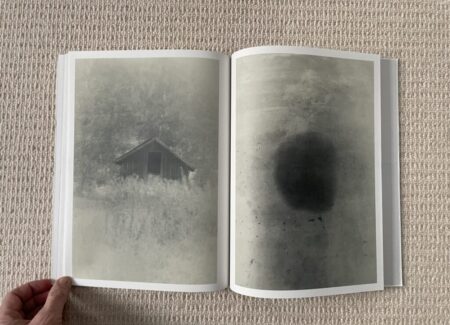

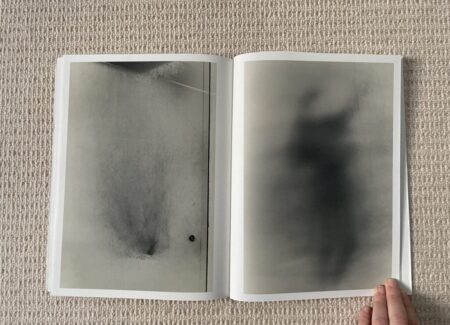

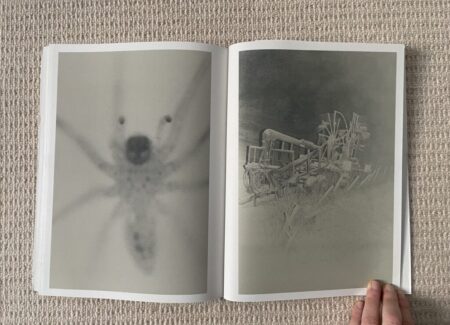

Rindal’s subject matter could hardly be more modest and ordinary, even forgettable in many cases, but his aesthetics intentionally transform these views into near abstractions. Many of his images document mountain landscapes, perhaps near his hometown of Fåvang, often seen at night and bathed in whitening flash. Dark trees, forests, houses, abandoned shacks, parked cars, and farm equipment stand idly in the silence. Rindal’s images examine these moments with intention, like memories that don’t quite coalesce into meaning. He stares up into the thickness of overhead branches or off into the distance again and again, the views eventually turning to blur or darkened mist, with electrical poles, flared lights, and nearby meadows similarly seeming to dissolve before our eyes. These places might house important personal history, but Rindal’s photographs soften and erode that specificity, the locations made evocatively secretive and anonymous.

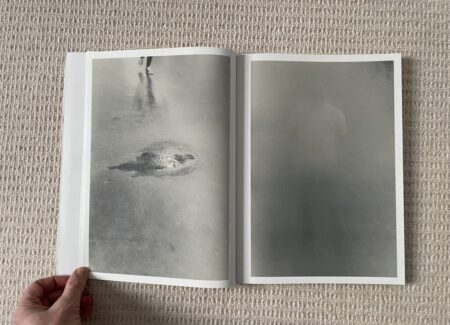

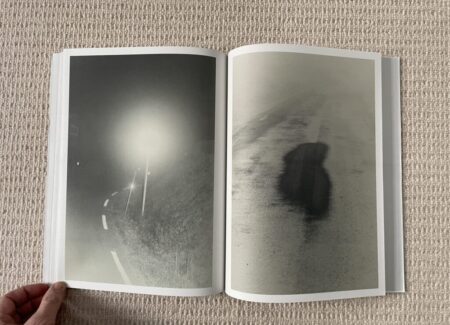

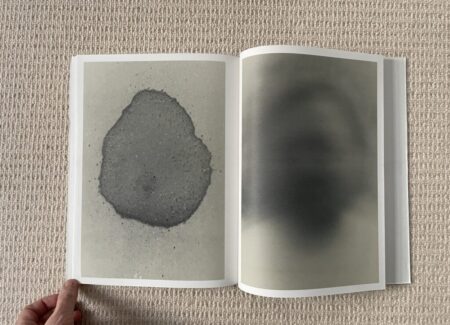

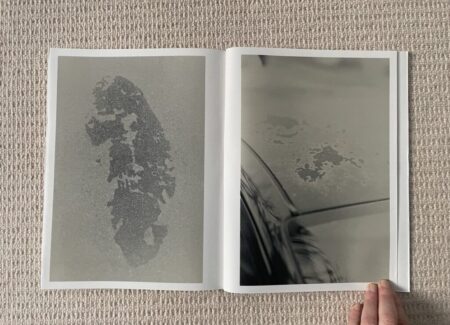

We might attribute the many images of roads in Stains & Ashes to the artist’s comings and goings, but again, Rindal pushes these views away from any concrete narrative, letting them settle into more shifting observations. Misty views down roads pile up, with car headlights poking through the foggy darkness or parked cars discovered in momentary flares of light. Spots of wetness, encroaching puddles, splattered dots, and other stains on the pavement become a subject of their own, each composition a meditative examination of form. Splotches and repaved areas give way to stains on stacked tires and rusted car hoods, expanding the theme to broader automotive motifs. Soon we have left the road behind altogether, with Rindal finding stains on paving stones, on a mattress, in the corner of a ceiling, on a door like charred smoke, on a table cloth, and on various exterior walls, some starting to look like watery sketched figures to our eyes that want to give them meaning beyond their mundane reality.

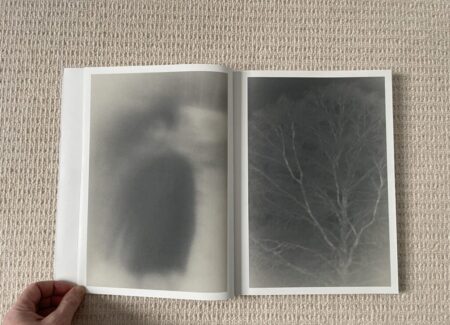

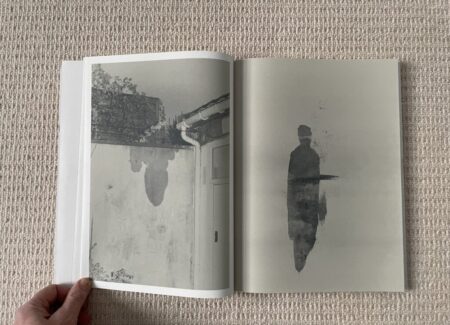

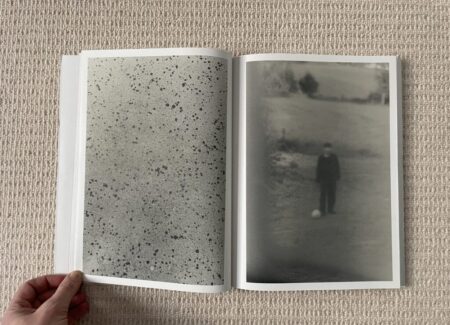

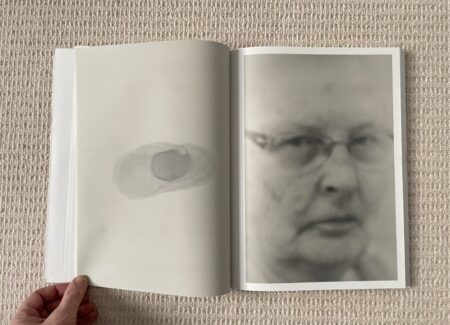

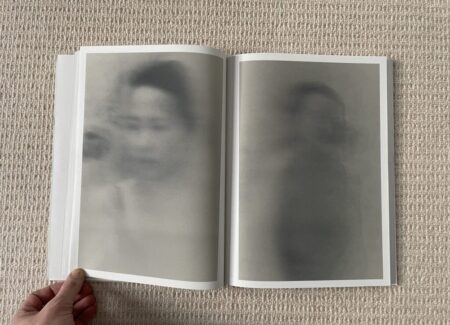

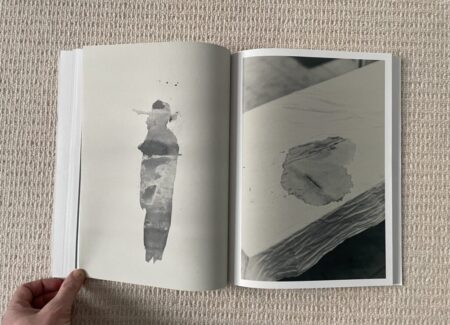

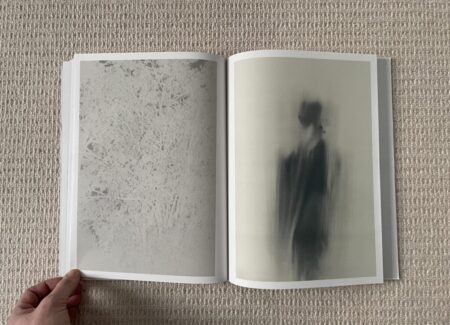

When people appear in Rindal’s photographs, deliberate blur, reflection, and enveloping mist alternately reduce them to obscured approximations, their indeterminate forms often creating paired echoes with his found stains when they are sequenced together. Figures and faces constantly slip away, like fading memories or hints of personas eluding our grasp. Even when we can find a detail to visually recognize, like a boy with a soccer ball, it too dissolves before our eyes, its meaning becoming hidden. Again and again, faces and bodies wander through destabilizing grain, like ghosts that refuse to reveal themselves fully. Sometimes only a step back and a squint of the eyes will help bring these images into some kind of focus that reveals they are human; in a few images, even this approach fails, the subjects becoming essentially illegible, turning an individual into a smudge or a darkly shifting shape and boiling the form down to an essence.

On a handful of pages, Rindal seems to have been experimenting with painterly mark making, turning gestures of watercolor or perhaps darkroom chemicals into forms that recall the stains and dissolving bodies he has discovered out in the world. These are essentially isolated marks on grey paper printed full bleed, with watery swirls and circular brushstrokes offering another layer of artistic reinterpretation, where the ideas in the photographs are sifted once more.

When these various approaches are then interleaved and sequenced into a single photobook expression, Rindal’s efforts at mood setting become most apparent. This is a book filled with fogs, mists, ghosts, reflections, shadows, blurs, flares, ashes, and yes, stains, the whole thing drowning in a fuzz of warm white noise. And while the noticing of artful stains has long been a favorite subject of photographers, Rindal takes that impulse somewhere new with this project. Stains & Ashes feels like a subtle meditation on photography’s ability to successfully communicate meaning. And by intentionally frustrating that goal in his pictures, Rindal places us in a kind of limbo state, where our instinctual effort to see patterns in stains or people in glimpsed forms is left to wrestle with inconclusive results. He asking us to apply a different kind of seeing to his photographs, where echoes and connections seem to be everywhere, but concrete clarity remains impossible. In this way, his photobook is an elegant exercise in photographic guesswork, filled with pictures that offer more questions than answers.

Collector’s POV: Ola Rindal does not appear to have consistent gallery representation at this time. Collectors interested in following up should likely connect directly with the artist via his website (linked in the sidebar).