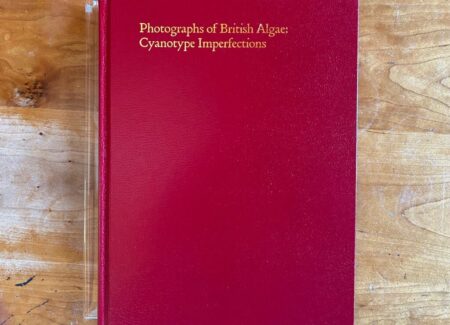

JTF (just the facts): Published in 2025 by GOST (here). Hardback with marbled end papers and gilded page edges, 199 x 256 mm, 160 pages, with 76 cyanotype images. Includes an essay by the artist. (Cover and page spreads below.)

Comments/Context: When Collector Daily last checked in on Mandy Barker in 2018, she had recently published her debut monograph Beyond Drifting: Imperfectly Known Animals. This book (reviewed here) collected Barker’s pictures of microscopic plastic particles, found and photographed off the coast of Ireland during a 2014 residency.

Bursting with evidence of industrial contamination, Beyond Drifting was partially intended as an environmental wake up call. But it was not a plain polemic. Instead, its clever design and historical references lifted it into the realm of Art—capital A. Barker adopted her title and inspiration from a 1828 memoir by the British naturalist John Vaughn Thompson. Beyond Drifting’s physical appearance was deliberately scuffed to appear archaic and shopworn, like a 19th century manual. The layout and captions played along with the ruse, employing myopic framing, faux-binomial nomenclature, and dusty handwritten labels for a period look.

The resulting tome was not just a chronicle of pollution, but a wry commentary on record keeping, presentation, and the scientific process. If one doubted that an oceanographer’s journal could be aesthetically intriguing, Barker’s monograph staked out the potential territory.

With her latest photobook, Barker fleshes out this territory in new and surprising ways. As with Beyond Drifting, its title and inspiration are adopted from a 19th century book. In this case it is Anna Atkins’s Photographs of British Algae: Cyanotype Impressions. Created in 1843, this hand-crafted album is generally recognized as the first book illustrated with photographs. It was conceived in photography’s primordial era, before the discipline had splintered into subcategories. Chemistry, art, and history were still integrated as a singularity. On one level Atkins’s book offered just what her title promised: a record of sea algae. But its aesthetic charms reverberated far beyond its data points.

Cyanotype Impressions (produced in several unique editions) has aged into a beloved classic. No sense trying to outdo Atkins. But a respectful tribute might be in order, and Barker has stepped up with a near perfect doppelgänger. The mimicry applies to the title of course, altered by just one word: Photographs of British Algae: Cyanotype Imperfections. But its images take the homage to an absurdly dedicated level.

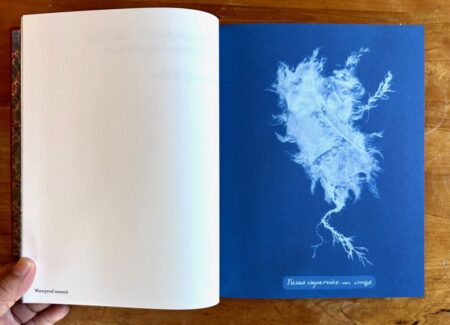

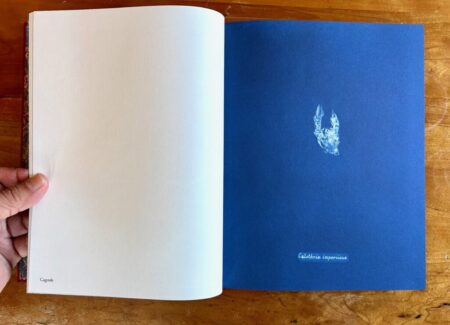

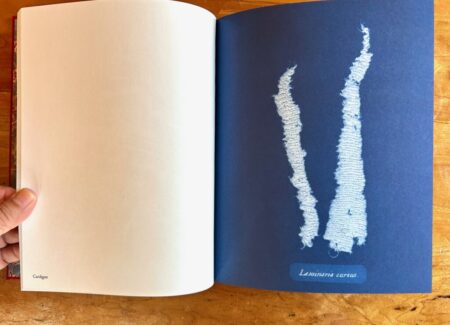

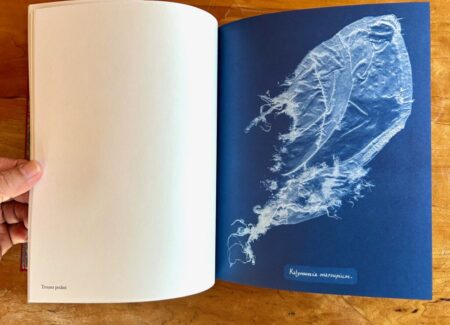

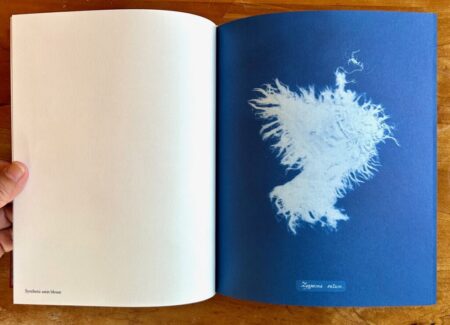

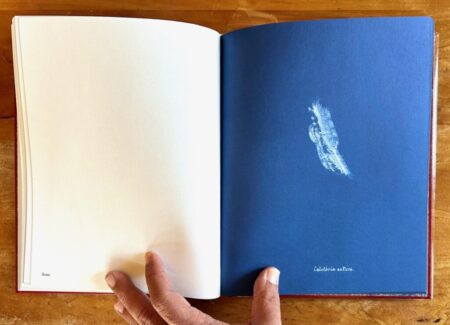

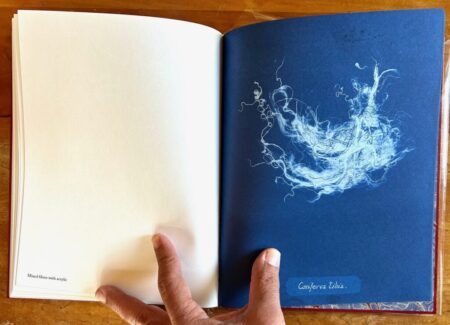

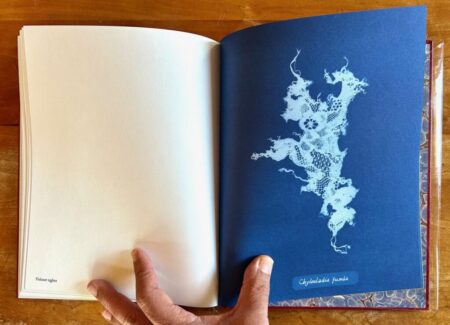

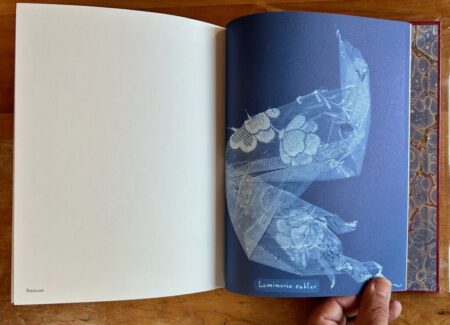

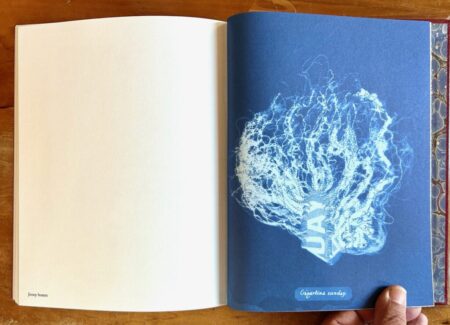

Barker mined the same location as Atkins for source material, the sea along the British coast. But instead of natural specimens, she sought discarded fabric. As she recounts the initial impetus, “in 2012, I found a piece of material in a rock pool that changed my life. Mistaking this moving piece of cloth for seaweed started the recovery of synthetic clothing from around the coastline of Britain for the next ten years.” Back in the studio she leaned on Atkins’s cyanotypes as direct models for her own staging and methodology. She dried and flattened her found fabrics in a Victorian press, then arranged them after Atkins. An 1843 photogram of the fuzzy sea creature Zygnema curvatum, for example, is transformed anew into a swatch of synthetic satin blouse. Not only does it look roughly similar to Atkins’s 19th century algae, Barker has conferred it a faux-Latin name: Zygnema sutum.

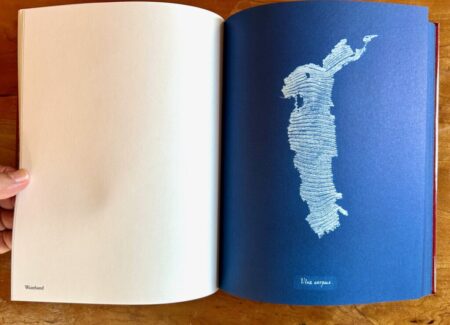

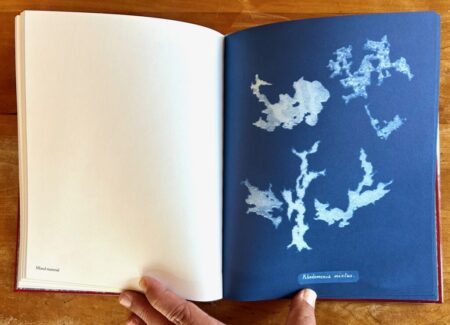

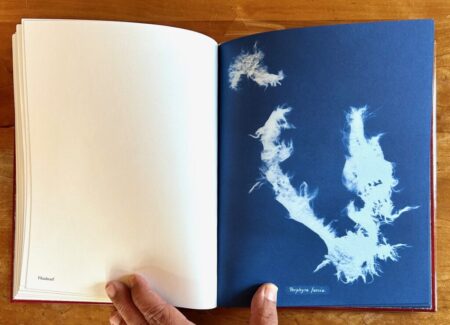

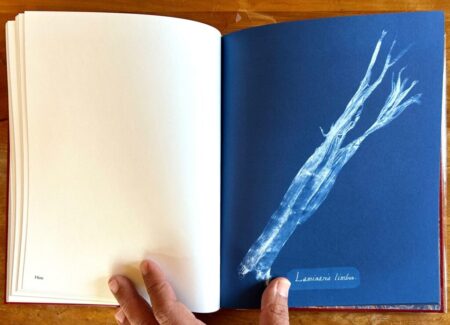

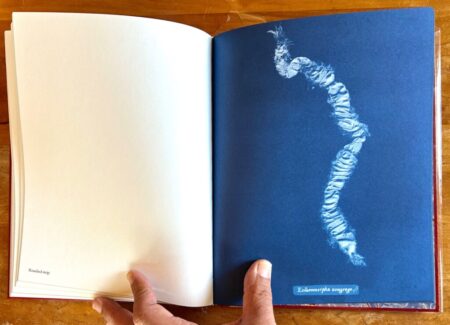

She applies the same treatment to other subjects, for example a vintage cyanotype of Chorda lomentaria. This appears to be some sort of kelp or seaweed which Akins has framed in a diagonal heap of gentle curves. For its modern counterpart, Barker takes aim at a long string of Lycra fibers. In reversed silhouette they vaguely resemble seaweed. Barker clinches the comparison by arranging them in a diagonal sweep. Viewed at a slight distance the form is virtually identical to Atkins’s original. Presto! Chorda super suo. Barker applies the same method repeatedly, birthing an array of imaginary species. She must have had fun inventing neologisms like Sargassum contraho, Ficus capillamentum, and Porphyra funda.

After browsing a few specimens, you might guess additional specs on your own. Barker was as diligent as any 19th century chemist. She handwrote her labels as a negative into her cyanotypes, just as Atkins did. She used J Whatman paper from the gilded age for authentic effect. She mixed and applied photo chemistry by hand, like Atkins.

Repeat these steps 203 times, bind the results in one volume, and you wind up with a contemporary twin of Cyanotype Impressions. If the analogue processes and full simulation are imprecise, that’s reflected in the new subheading Cyanotype Imperfections. Thus was born the initial leather-bound prototype which Barker created a few years ago. With marbled end papers, hand scripted notes, and cyanotyped index and annotations, it was a limited edition pièce de résistance on par with Atkins.

The book published by GOST is a scaled down version of Barker’s original, honed for a trade edition in a wider print run. The red cover remains, but it’s been converted to leatherette with foil stamped title. The marbled end papers have carried over too, along with gilded page edging. While these features are roughly intact, the original notes, preface, and manuscript details have been ditched, replaced with a single essay by Barker. “I see this book as a discussion point, a call to action,” she writes hopefully, “and by publishing the work to circulate and share will reach a wider audience.”

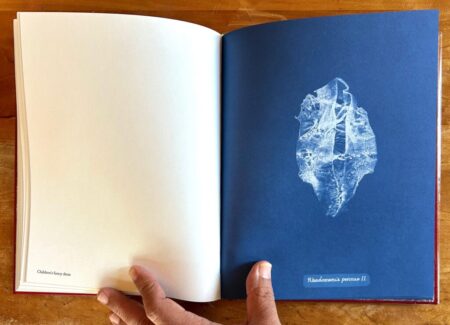

Reaching such an audience sometimes requires compromise. In this case the primary concession is sheer volume. Barker’s original 203 images have been boiled down to 76 for the GOST edition. Each one occupies the right page of a double spread, opposite a plain-English caption (not handwritten, alas, but in Doves Press typeface for Victorian effect), in blue/white alternating rhythm.

If labels like Ribbon, Shirt button hole, and Children’s fancy dress don’t have quite the same gravitas as Linnaean descriptions, they are easier for modern readers to interpret. More importantly, they contribute to a thoughtful sequencing motif. In a delightful twist, it turns out the book’s images are ordered by bodily proximity. Outerwear such as jackets and trousers appear first, followed by increasingly intimate items like lingerie, underwear, and petticoats. The last page is reserved for Barker’s personal ruminations. Is fashion’s allure merely skin deep? A slight scratch below the book’s surface reveals the answer.

Like the Atkins classic on which it is based, Cyanotype Imperfections resists easy pigeonholing. Barker diffuses like plankton across a multi-genred middle depth. It floats near the nexus of environmentalism, analogue photography, and bibliophilic homage. For future oceanographers researching industrial pollution, this book might be a valuable resource. “Every year,” according to GOST, “the fashion industry is responsible for more greenhouse gas emissions than all international flights and container ships combined.” Who knows, in a world awash in excess clothing, perhaps Cyanotype Imperfections could serve as an impromptu field guide or checklist? Or perhaps it might spur reform in clothing production, or the use of biodegradable fabrics, or other measures.

All are possible. That said, such practical matters seem like a secondary concern for Cyanotype Imperfections. To this outside witness, this book feels spurred more by adulation than activism. Above its other facets, it comes across as a grand tribute to Atkins. Barker goes to great lengths to spruce up her legacy. Her Atkins-Barker site (here) is encyclopedic, spilling over with raw information like an ocean of PFAS. Her original Cyanotype Imperfections is just as exhaustive. She’s put her nose to the grindstone. Atkins would be impressed.

GOST’s trade version is a slightly different beast, yet still a triumph. It manifests the sort of single-minded drive and ambition which was not uncommon among 19th century scientists. In the contemporary era of tweets and hyperlinks, multi-year projects like Barker’s are more vulnerable to distraction. Many sputter out like spent waves. But they can still accrue, imperfectly, if one knows where to focus.

Collector’s POV: Mandy Barker is represented by East Wing (here). Her work has little secondary market history at this point, so gallery retail likely remains the best option for those collectors interested in following up.