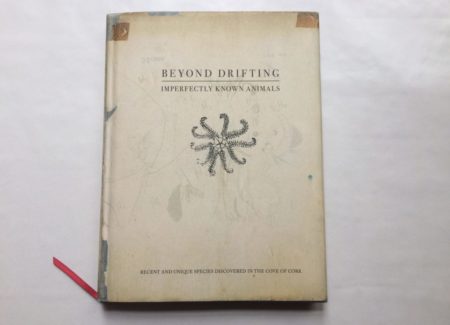

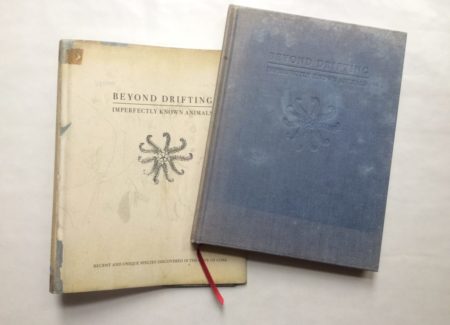

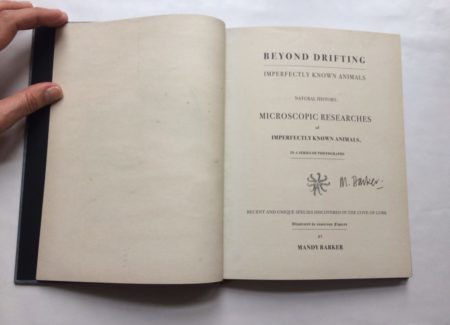

JTF (just the facts): Published in 2017 by Overlapse (here). Cloth hardcover with dust jacket, section-sewn binding with book ribbon, interior dip-in and hand finishes, 104 pages, with fifty-nine color photographs and numerous illustrations throughout, 7 x 11 inches. Includes plate descriptions, texts by Mandy Barker and Dr. Richard Kirby, as well as a quote by the late marine biologist and author Rachel Carson. Designed by Mandy Barker and Tiffany Jones. (Cover and spread shots below.)

Comments/Context: In the early 1820s military surgeon John Vaughn Thompson wandered the southern shores of Ireland, searching for unknown marine life. Using a small, muslin towing-net, the self-taught naturalist eventually came across microscopic creatures, which, lacking a proper name, he described as “imperfectly known animals”. Thompson published his significant discoveries as a memoir in 1830. Titled Zoological Researches and Illustrations, it combined texts and – as photography hadn’t yet been invented – drawings of the forms he observed under a microscope. The young Charles Darwin carried his book during the second voyage of the HMS Beagle. Today, Thompson’s “imperfectly known animals” are known as plankton.

The beauty of discovery is that it often occurs in unexpected ways. As you can already tell from its title, Mandy Barker’s Beyond Drifting: Imperfectly Known Animals is a dialogue with Thompson’s discoveries. However, Barker’s book, introducing twenty-six new “micrographic specimens”, came about from her 2014 residency at The Sirius Art Centre, a former yacht club, situated in Cobh Harbor, Cork County, Ireland. Just before starting the program, Barker attended an International Marine Debris Conference in Berlin, where she met the marine biologist Dr. Tom Doyle, who, coincidentally, was not only doing research in Cork, but also introduced her to Thompson’s pioneering work.

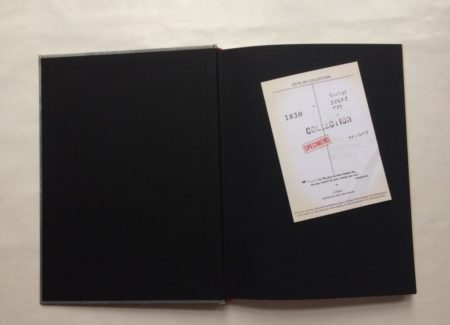

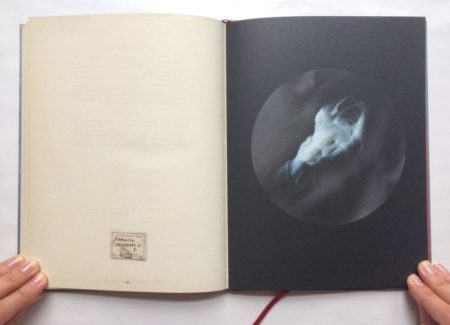

Drawing a fine line between art and science, Beyond Drifting takes the form of a Victorian-era science album, and in doing so, it lends itself the silent authority that only time and handling can bestow on an object. In fact, it took me a second (and for my hands to trace its cover, edges, and pages) to realize that the book’s seemingly well-worn dust jacket; its stained and washed-out cloth cover; as well as its front free endpaper with a facsimile, tipped-in, creased Cobh Library checkout card with faded stamps and pencil notes; are not actually old, but are made to look so. Even the book’s fragrance is part of this elaborate disguise, as it drifts between the briskness of new paper and the sweet-musty scent of a frequently checked-out library book. As you reach the title page and make your way into the book, the pages are thick and yellowed and immediately alert you that this is not going to be a quick flip-through, but a rather a slow, deliberate, dive.

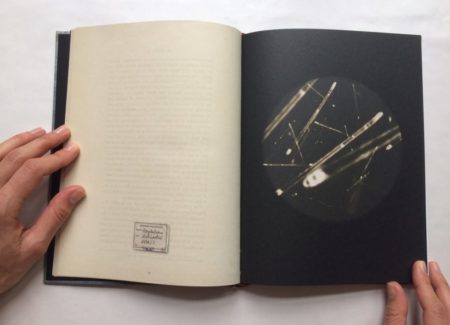

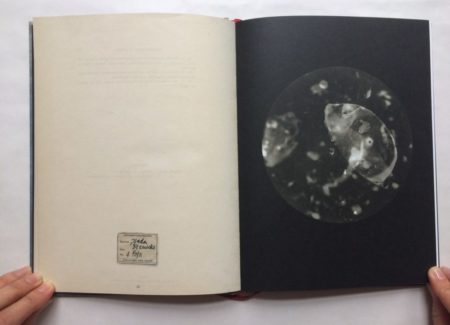

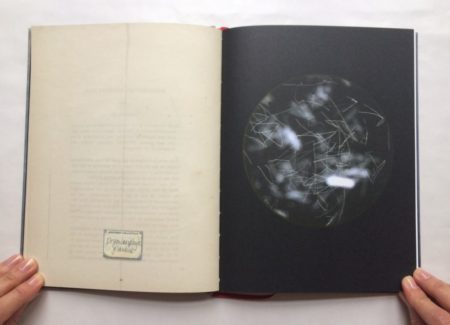

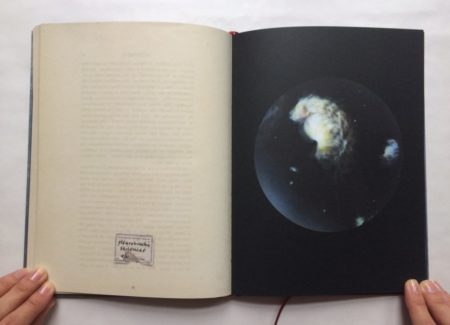

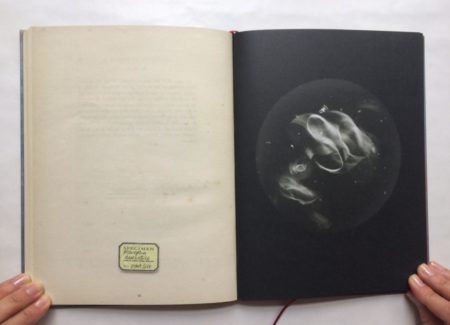

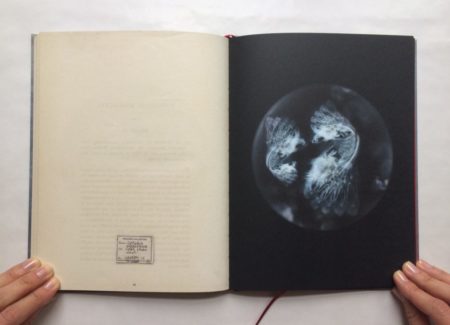

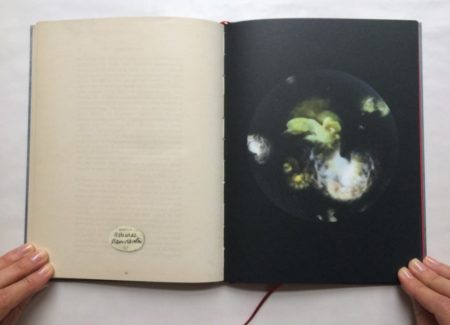

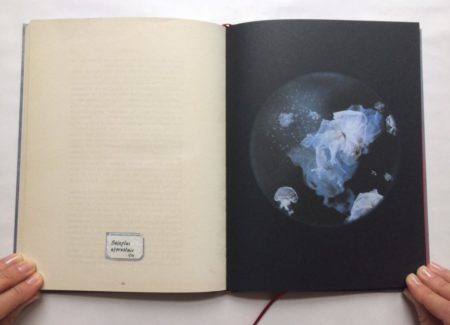

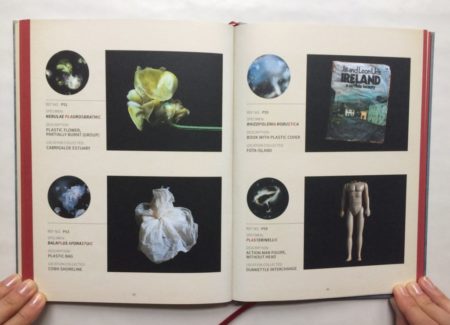

Barker’s photographs of her enlarged micrographic specimens make up the main body of Beyond Drifting. One per page, each of them is paired with antique specimen-label on the opposite page, which is inscribed with a Latin sounding name (such as Saplitta Setosica, Fpuslaes Maticaus, or Phronilasteri Crae). As if seen through a microscope, they float within a circular frame and are printed on lush, black paper that, intuitively, recalls the hidden depths of the sea. In fact, these tiny creatures appear to move so rapidly that their images are often blurry, and, therefore, only hint at their actual features.

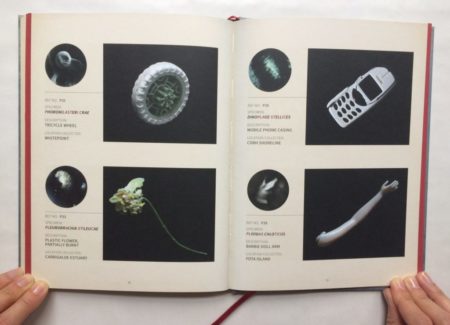

The best of Barker’s images, however, allow you to zoom-in a bit closer. And while the abstract, or invisible, materializes, your associations run free. There is, for instance, Copeopod Langisticus, a perforated tangle of white ribbons, that reminds me of the helix structure of a virus or some bizarre-looking worm – while Pleurobrachia Stileucae looks like a well-stuffed yellow dumpling or a somewhat obese sea horse. Among my favorite images are the more ephemeral, translucent formations, such as the slightly bent wings of ghostly Ophelia Medustica, or the smooth jellyfish-twirls of Balaplus Aforatuic.

The longer you look at these otherworldly images, there is something ineffably delicate, at times, vulnerable, that surfaces and goes beyond Barker’s photographs themselves. The pages’ slight creases and mold spots (even if fake), as well as the faint drawings and bleed-through texts, both of which Barker took from Thompson’s original publication, add to this sensation. However, it is primarily the book’s opening text, defining plankton as a “diverse group of organisms that live in the water column, drifting, not able to swim against the current” – the crucial role they perform not only in the global carbon-cycle but also at the base of the food-chain, that they “create the characteristic smell of the sea”, and “are even instrumental in cloud formation” – that provokes in me, a feeling of tenderness and the urge to protect.

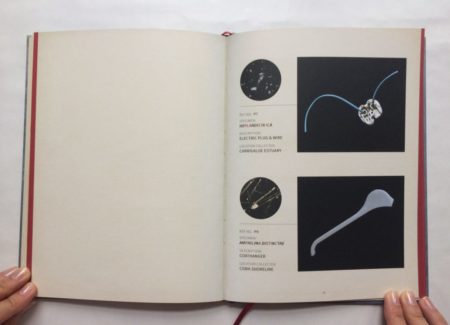

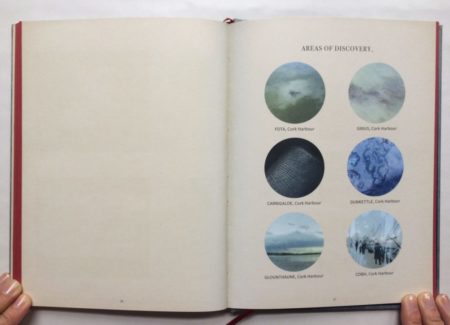

The surprise comes in the final third of Beyond Drifting, as you learn not only about the true origin of Barker’s plankton, but also how much protection is, indeed, needed. To access the red-edged pages of the book’s PLATES section, you must break a red-and-white “CONCEALED HAZARD” seal. Like any good scientist, Barker has carefully catalogued each specimen and paired their miniature reproductions with larger, sharper photographs of their sources. As it turns out, her specimens are not newly discovered animals, but pieces of plastic detritus that she collected from the same shores Thompson visited two-hundred years before. It is here, where you learn that Ophelia Medustica is actually a pram wheel – and Pleurobrachia Stileucae a partially burnt plastic flower, and that their names are imaginary, each including letters forming the word “plastic”. The list of detritus goes on to include packaging, brush bristles, a cell-phone case, electrical wires, a headless action-figure, and the arm of a Barbie doll. As you recover from this well-planned disenchantment, you’ll find images of the locations of discovery, as well as three short texts providing insights into Barker’s process and motivation.

Beyond Drifting isn’t her first project drawing attention to the massive environmental problem of plastic marine-pollution. Barker decided to become a photographer after revisiting the beaches of her childhood, and finding that these shores were increasingly soiled by washed-up man-made waste, particularly plastic. The defining moment of her engagement was when she saw a partially submerged car along with a refrigerator on a coastal nature-preserve. For this book, Barker has engaged with the impact of plastic debris, which eventually decomposes into miniscule particles: plankton are now ingesting these micro-scraps, mistaking them for food. Even if the consequences of this ingestion are not yet fully understood, it does not take a marine-biologist to understand the obvious ecological harm.

What I find so remarkable about Beyond Drifting, especially considering Barker’s commitment and persistent activism against plastic pollution, is that it could have easily fallen into the trap of being plainly, and as such, uninterestingly, didactic. Yet, it doesn’t. Barker’s intelligence and spunk in designing this book is the reason for its success. In addressing a contemporary environmental problem in the guise of a 19th century album, she does more than connect the viewers with the past and nature, a time where the oceans were clean. Instead, we are allowed to make our own discovery, and in doing so, reconnecting with sense of wonder and mystery, when looking at photographs. In this way, Beyond Drifting also circumvents our oversaturation and numbness when confronted with difficult images.

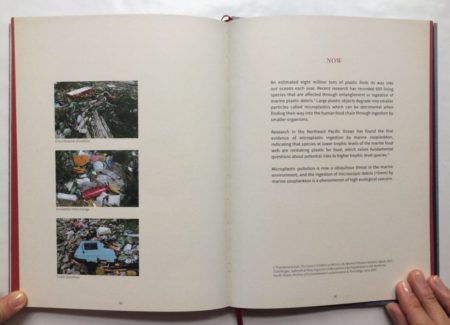

Barker began her project by making traditional documentary photographs of beaches and their debris (three of which are included in the book’s text section). When showing these photographs to friends and acquaintances, she realized that the images did not succeed, as they did not hold the viewers’ attention. As Barker writes, she consequently decided to “trick” the viewer by placing the objects on a black background and photographing them with expired film, faulty cameras, multiple exposures, and a slow shutter-speed, as she moved her plastic samples to imitate the movement of plankton. These technical and representational flaws became a metaphor for the “imperfection” of her subjects themselves.

In the simplest sense, Barker’s photographs are beautiful images of inanimate objects that, through the means of photography, become living organisms. It is her texts that break this spell. Combing these two facets, Beyond Drifting holds a unique spot somewhere between the aesthetics of Anna Atkins and William Henry Fox Talbot, and the disruptive approaches of Adam Broomberg and Oliver Chanarin. And in doing so, Barker not only draws attention to a major ecological and environmental crisis, but also proves, once again, that photography’s truthfulness is as seductive as it is misleading.

Collector’s POV: Mandy Barker is represented by East Wing Gallery, Doha (here). Barker’s work has little secondary market history at this point, so gallery retail likely remains the best option for those collectors interested in following up.