JTF (just the facts): A total of 9 photographic works, variously framed and matted, and hung against white walls in the main gallery space, the entry area, and the back office area. (Installation shots below.)

The following works are included in the show:

- 5 photogram, gelatin silver print, 1989, 1997, 1999, sized roughly 39×29, 40×30 inches

- 1 set of 12 photograms, gelatin silver prints, 1995, in variously descending sizes (from roughly 31×22 to 7×5 inches)

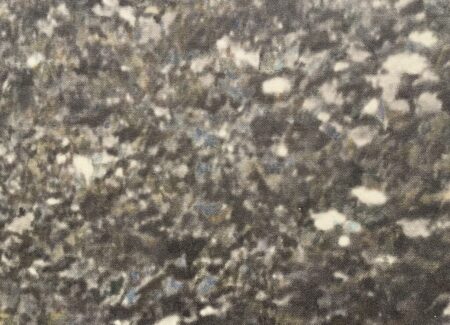

- 1 photo emulsion and acrylic on canvas, 1971, sized roughly 71×101 inches

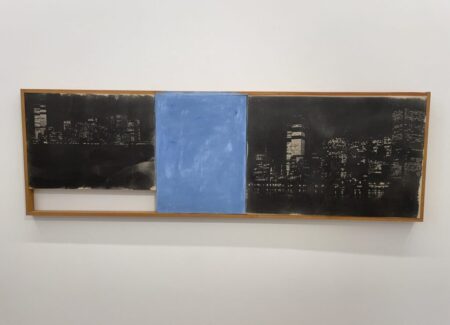

- 1 acrylic, photo emulsion on canvas, wood, 1978, sized roughly 27×84 inches

- 1 set of 2 toned gelatin silver prints, 1996, each sized 24×20 inches

Comments/Context: One of the joys of staging career museum retrospectives comes in seeing artists that weren’t appreciated enough during their most active years finally get a slice of much deserved recognition. It’s easy enough to plan the surveys of well known artists with household names, who have been safely celebrated again and again and who will be sure to draw in the crowds. But it’s much harder, and perhaps more satisfying, to shine the spotlight on a select few of those who continued to make decades of thought provoking work, even when others were getting more attention.

SFMOMA has recently organized a career retrospective for Kunié Sugiura, a multi-talented Japanese artist/photographer who certainly fits into the category of a somewhat lesser known artist worthy of a fuller re-examination (the exhibition runs from April 26 – September 14, 2025, here, with a catalog published by MACK here, cover shot above.) Now in her early 80s, Sugiura has been actively experimenting since the mid-1960s, crossing over from one medium to the next, and quietly expanding the aesthetic definitions and boundaries of photography in particular along the way. Of course, she’s consistently had gallery support in New York, where she lives and works, and we’ve visited many of her shows in the past decade or so, including those in 2013 (reviewed here), 2015 (reviewed here), 2017 (reviewed here), and 2023, which have often placed her older and newer works in dialogue.

Anchored by two early works from the 1970s, this tightly edited show returns to some of Sugiura’s most enduring innovations, offering an easy-to-digest guide to where her artistic strengths lie. The wall-filling Island_2 (from 1971) comes from Sugiura’s “Photocanvas” series, which takes as its subject the rough stone surface of a Coney Island breakwater. Seen in extreme close-up, the rock face dissolves into tactile spots of mottled light and dark, which Sugiura has then printed on canvas and then augmented with subtle color tones (as seen in the detail image above), with flecks of blue and brown adding to the shifting all-over abstraction. This early photo/painting hybrid was included in Sugiura’s first solo gallery show in NY in 1972, but has been stored in her Chinatown studio ever since; it’s important because it shows Sugiura experimenting with the ways photographic texture could be enhanced and expanded by the techniques of painting.

By the second half of the ’70s, Sugiura had evolved her approach a bit, still playing with printing photographs on canvas but now making her wall-based constructions more sculptural, with panels of photographs mixed with areas of flat painted color, connected by wooden strips and frames. Tip (from 1978, from the series “Photopainting”), on view for the first time, places a painted sky blue rectangle between two nighttime views of the city (including the World Trade Center towers) as seen from the water. The sparkling lights in the buildings become their own kind of dappled texture, with the gestural painting in blue (almost like day versus the night nearby), the loosely painted emulsions, the opening (created by one panel being smaller than the other), and the rough wood frame adding a hand-crafted, more personal contrast to the machined, geometric shapes of the metropolis.

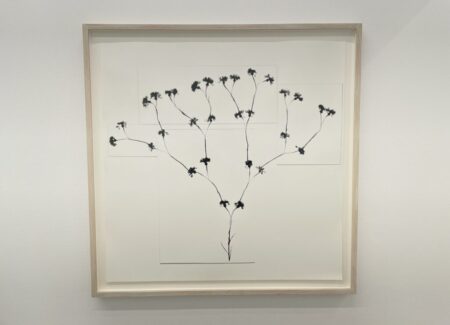

In the 1980s, Sugiura left these painting-adjacent ideas behind and began experimenting with camera-less photograms. Sugiura studied with Kenneth Josephson at SAIC in the late 1960s, who himself had studied with Harry Callahan and Aaron Siskind, so her artistic lineage with this kind of approach connects step-wise all the way back to the New Bauhaus and László Moholy-Nagy. Many of her photograms used flowers and other botanical specimens as their ostensible subject matter, but her approach was far more conceptually controlled and ordered than simple blossom and leaf silhouetting. The 1989 work “Split & Pressed Cornflowers” finds Sugiura taking positive cornflower photograms and meticulously arranging them in a branching structure, with each split leading to two blossoms, and each blossom then leading to another split, like a genealogy diagram. The resulting arrangement is both effortlessly natural and rigorously scientific, filling a wall with dividing complexity.

Throughout the 1990s, Sugiura played with these kinds of photogram forms, using cornflowers, tulips, mums, and other flowers purchased locally. “Upside Down Pyramid” (from 1995) arranges positive and negative pairs of floral photograms in descending sizes, with differing blossoms iteratively stepping down smaller and smaller towards the floor. She also made various arrangements of densely stacked stems, in both positive and negative tonalities, that could be hung either horizontally or vertically; “Stacks Tulips C1 and C1 positive” (from 1996) puts reversed images next to each other, like a fluidly gestural reflection. (And in the spirit of full disclosure, we have one of these stacked photograms, of cornflowers layered up and down, in our own collection.)

But this ordering of compositions wasn’t enough for Sugiura. By the second half of the 1990s, she was introducing thin filaments of thread to the floral specimens, adding lines, grids, and other geometric structures. “Mum Curtain” (from 1997) is what its title implies, a set of vertical strings with small blossoms attached intermittently, like a loosely beaded curtain; Sugiura plays with the distance between the strings, the number of blossoms on any given string, and the distance between the blossoms, creating syncopated visual rhythms that are slowly reduced to a single note. “Meshes #1 Positive” (also from 1997) takes similar blossom-decorated threads and arranges them into an ordered grid, with individual flowers now placed on line segments or at intersections. And just a few years later (in 1999), Sugiura encouraged this process to get even more expressive, with wiry lines that twist, wander, and drift, connecting blossoms into circles, halos, and other hovering forms, in a few cases, adding watery chemical washes and splatters to further amplify the energy.

While this small show can’t possibly provide as sweeping a survey of Sugirua’s ideas as the SFMOMA retrospective, it does ably hit a few key projects and aesthetic examples that are worth understanding. What stands out about Sugiura’s work, in nearly all the forms it has taken across her long career, is how consistently she merges formal rigor with understated elegance, and how she has continued to challenge the intersection points between mediums. I remain drawn to the way Sugiura’s artistic mind employs structure, her sophisticated approaches to order and arrangement finding elemental grace almost regardless of her subject matter. Ultimately, it requires a keen sense of balance to do what Sugiura has done so often, and this succinct sampler captures the essence of that layered search for equilibrium.

Collector’s POV: The works in this show range in price from $32000 to POR. Sugiura’s work has had very little secondary market activity in the past decade, so gallery retail likely remains the best option for those collectors interested in following up.

Superb, confident, clear-visioned work.