JTF (just the facts): A group show consisting of works by 15 artists/photographers, variously framed and matted, and hung against white/cream colored walls in a series of rooms on the second floor of the museum. The show was organized by Oluremi Onabanjo, with assistance from Chiara Mannarino. (Installation shots and film stills below.)

The following works are included in the show:

- Air Afrique: 12 magazines, 1964, 1965, 1966, 1968, 1972, 1985, 1994, 1996, 1998; 1 metal pin, 1965; 1 key ring, 1966; 1 vinyl record, 1969; 1 set of 4 books with hardcover, 1970; 2 boxes of 6 volumes each, 1970; 1 matchbox, 1970s; 1 vintage suitcase, 1970s; 1 set of 54 playing cards, 1980

- Felix Akinniran Olunloyo: 6 gelatin silver prints, c1950-1970

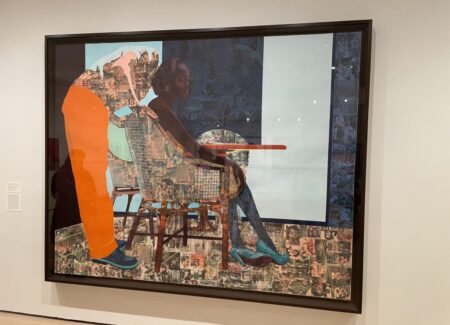

- Njideka Akunyili Crosby: 1 acrylic, acetone transfer, charcoal, pastel, marble dust, and collage on paper, 2013

- James Barnor: 2 gelatin silver prints, c1954-1959/2018-2020

- Kwame Brathwaite: 4 inkjet prints, 1964-1968/2024

- Jean Depara: 6 gelatin silver prints, c1960, 1960/later, c1960/later, 1975/later

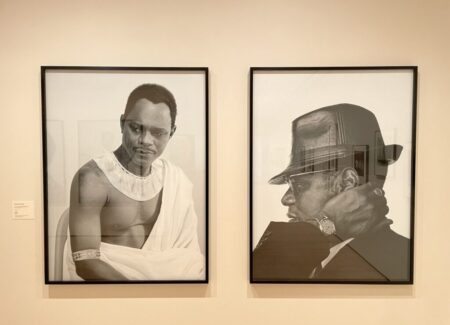

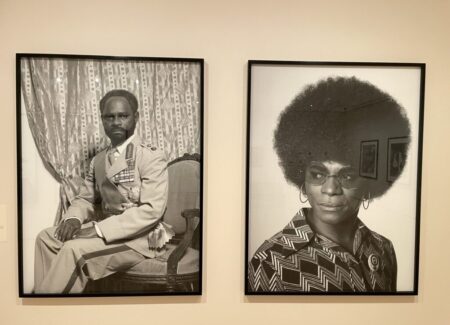

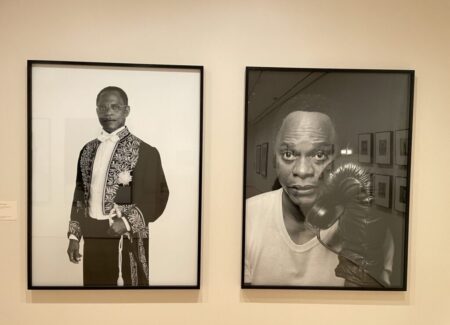

- Samuel Fosso: 10 gelatin silver prints, 2008

- Janet Jackson/Joni Mitchell/Q-Tip: 1 single channel video, 1997, 4 minutes 10 seconds

- Oumar Ka: 1 gelatin silver print, 1969-1968

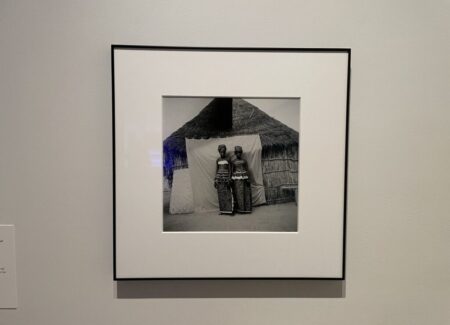

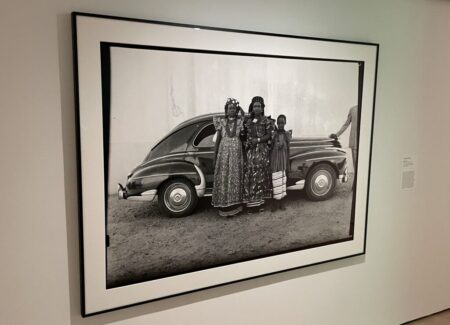

- Seydou Keïta: 9 gelatin silver prints, c1952-1956, 1954/later, c1955, 1956, 1956/later, 1956-1957/1997, 1956-1957/later

- Ambroise Ngaimoko: 3 gelatin silver prints, 1974/1998, 1976/1998

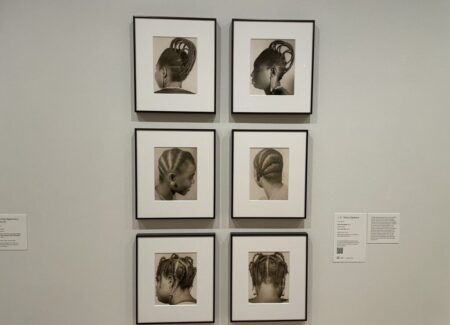

- J.D. ‘Okhai Ojeikere: 3 sets of 2 gelatin silver prints, 1970, 1971, 1973

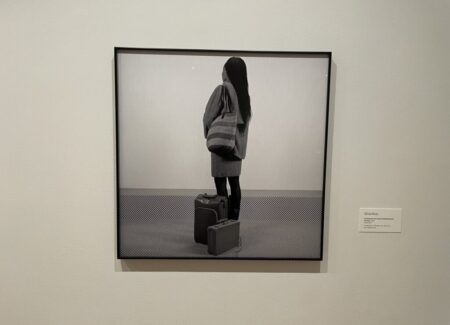

- Silvia Rosi: 4 inkjet prints, 2024; 1 set of 3 inkjet prints, 2024

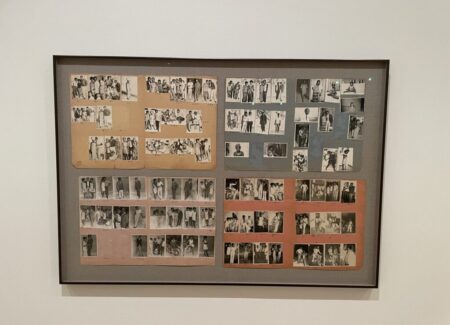

- Malick Sidibé: 4 gelatin silver prints, 1962/2006, 1963, 1963/2006, 1966; 1 set of 19 gelatin silver prints mounted on paper, 1967; 2 sets of 22 gelatin silver prints mounted on paper, 1970; 1 set of 24 gelatin silver prints mounted on paper, 1973

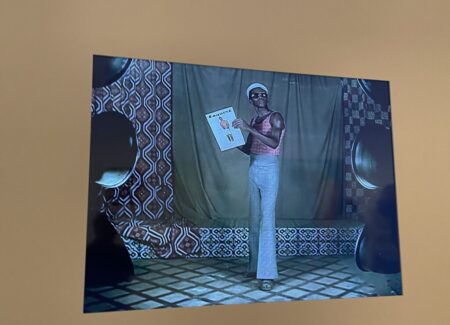

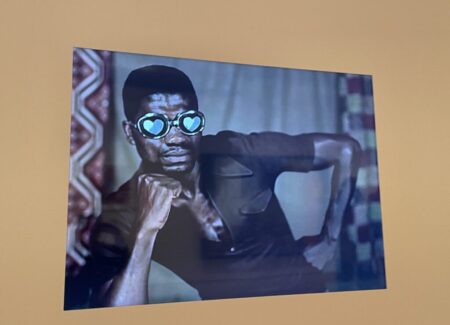

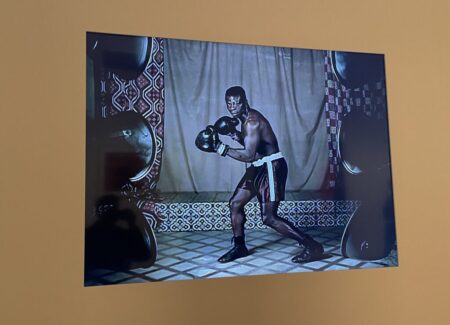

- Sanlé Sory: 17 gelatin silver prints, 1970-1985

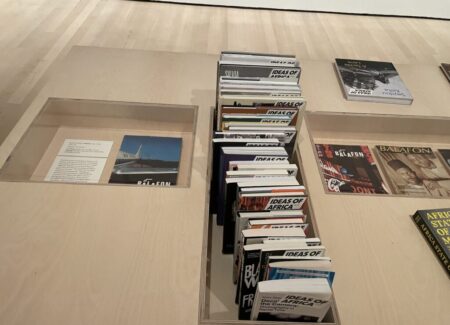

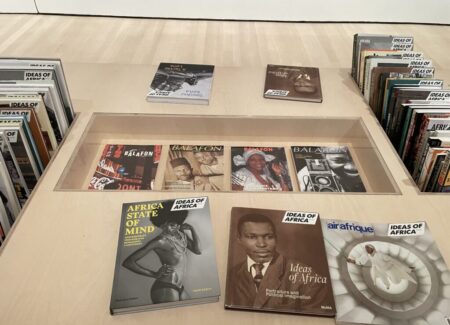

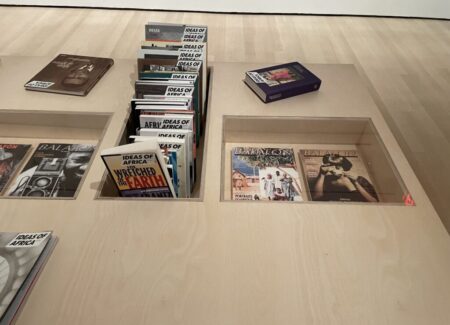

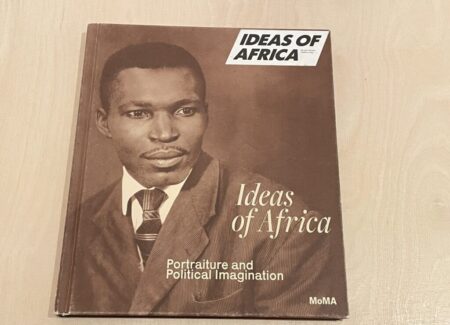

A catalog of the exhibition has been published by the museum (here). Hardcover, 9×10.5 inches, 140 pages. Edited by Oluremi C. Onabanjo, with contributions by Brent Hayes Edwards, Momtaza Mehri, V.Y. Mudimbe, and Yasmina Price. (Cover shot below.)

Comments/Context: It seems intuitively obvious that the purpose of a formal studio portrait is to capture your likeness when you look your best. And in the early 2oth century, when photography became inexpensive and functional enough to spread around the world, people from all walks of life went to local studios to have their portraits taken, often bringing their spouses, children, and extended families, and wearing their most formal suits, their best dresses, and their most elegant jewelry, with the hope that the resulting picture would somehow magically capture the very best version of themselves that they might muster. Their aesthetic choices also quietly signaled status, social position, power, and wealth to all that would look at the portraits years later.

But of course, not every studio portrait made was so somber or serious; many captured moments of frivolity, playfulness, and joy, or experimented with setups and fashions to allude to professions, interests, hobbies, or regional activities. But in the early days of African studio portraiture in particular (in the 1950s and 1960s), something else started to happen when people came to the studio – aspiration crept into the logic of portraiture. Many sitters still wanted to have portraits made in their best looks, but more and more asked to documented as who they wanted to be, rather than who they actually were. And at that moment, in nations across the continent, they wanted to be a range of things: “modern”, cool, international, funky, rich, Western, politically aware, stylish, and much more broadly African than ever before. And so the local studio photographers responded to the demands of their customers, still working hard to make them look their best, but adapting their available fashions, props, and backdrops to encourage more imaginative and expansive identity creation.

This smartly edited show takes this flowering of African imagination as its core premise. Starting from a foundation of images drawn from a 2019 gift from Jean Pigozzi (whose impressive collection of African photography also provided many of the images in the recent Seydou Keïta retrospective, reviewed here), the show expands its line of visual argument to include both photographers from the wider African diaspora and more contemporary examples from artists of African descent. The result is a show that builds upward from early examples, coalesces into a fuller thematic pattern, and then expands into a broader sweep of thinking that steps forward to the present.

For many visitors, the story of African studio portraiture might seem to be a simple two-artist setup in a single country, with the pairing of Seydou Keïta and Malick Sidibé from Mali at the center of the art historical discussion. And while Keïta and Sidibé have been deservedly celebrated as masters of the genre, this show pulls back to place them on essentially equal footing with a handful of somewhat lesser known studio photographers working at roughly the same time in various countries around the urban cities of West and Central Africa. Starting in the 1950s and extending through the 1970s, plenty of voices are added to the mix: Felix Akinniran Olunloyo and J.D. ‘Okhai Ojeikere from Nigeria, Jean Depara and Ambroise Ngaimoko from the DR Congo, Sanlé Sory from Burkina Faso, and Oumar Ka from Senegal. And while some artistic cross pollination and circulation was perhaps possible amongst these and other studio practitioners, it’s also altogether likely, given the cultural trends of the times, that the innovation of aspirational image making was simultaneously “invented” in several separate places at once.

A swing through the galleries highlights a range of different styles and incremental approaches among the artists. Keïta employed sophisticated fabric patterns and added modern props like a radio and a Peugeot car. Sidibé made countless party pictures, capturing the cool fashions and exuberant dance moves of the younger generation. Akinniran Olunloyo noticed the elegant nuances of how headscarves were tied, while Ojeikere paid close attention to the complex architecture of woven hair styles. Depara experimented with photocollage and montage to bring different motifs into his portraits. Ngaimoko softened his views with more casual and comfortable poses. And Sory encouraged more extreme role playing and identity inhabiting, in images featuring a gunman, a traveler, an intellectual, a boxer, a guitar player, and an “American” in sunglasses and rolled up jeans. In aggregate, the throughline of the “golden age” of African studio portraiture is much deeper and more heterogenous than we might have thought.

With this historical context now solidified, the show reaches out to expand the idea of imaginative identity, first to the work of diasporic African artists living elsewhere. Redefining black beauty to include African motifs was of interest to both James Barnor (who got his photographic start in Ghana, but ultimately moved to the United Kingdom) and Kwame Brathwaite (who was from the United States.) Both worked extensively with black fashion models, and incorporated headscarves, jewelry, and other fashionable looks into their portraits, boldly expanding the boundaries of beauty to better include black women. The in-flight magazine of the Pan African airline Air Afrique had similar aims, filling its covers (as seen in vitrines and cases) with various forms of African positivity.

Ideas of Africa then jumps forward to the 21st century, offering examples of how the original African studio portraiture motifs have been evolved, transformed, and sampled by contemporary artists. Given their towering scale, Samuel Fosso’s large scale self-portraits grab plenty of attention in this exhibition, and that’s appropriate, as Fosso’s works push the concept of aspirational identity creation to its logical endpoint. Fosso could easily have since been included at the end of the earlier period of African studio portraiture, as he ran his own portrait studio in the Central African Republic starting in his teenage years (the mid 1970s), and made singular portraits of himself and his clients featuring brash expressions of modernity and individuality. His landmark series “African Spirits” from 2008 extends those initial ideas of aspirational playacting into painstaking recreations of images of some of the important leaders of African independence, with Fosso himself taking on the roles of Nelson Mandela (from South Africa), Leopold Senghor (from Senegal), Kwame Nkrumah (from Ghana), Halie Selassie (from Ethiopia), and Patrice Lumumba (from DR Congo); in the series, he also inhabits a handful of famous black Americans, including Malcolm X, Angela Davis, and Tommie Smith making his famous “Black Power” salute at the 1968 Olympics, further reinforcing the diasporic connection between Africa and America.

The echoes of the photographic past continue into the final room of the show, where the original ideas have now been actively reworked and reinterpreted. Janet Jackson recreates the look and feel of many African studio portraits in her 1995 music video for “Got ‘Til It’s Gone” (which samples Joni Mitchell), including posing herself with a radio in an homage to an image by Keïta. Njideka Akunyili Crosby does a related kind of sampling in her 2013 painting “And We Begin to Let Go”, using solvent transfer to build surfaces out of densely collaged portraits and images. And Silvia Rosi reimagines the classic structure of the studio setup, obscuring and “disintegrating” her self portrait personas with interrupting flowers, luggage, and a photo album held on her shoulder. In each case, we can follow the visual connection back to the past, but feel it re-energized by the concerns of the present.

Once this entire chronological continuum of identity creation has been laid out, and is then matched by the timeline of political movements that led to independence in various African nations and civil rights in America in the 1960s and 1970s, it becomes clear that expressing personal individuality via studio portraiture in Africa (and its diasporic elsewhere) directly coincided with larger feelings of Pan-African solidarity and international connection. Once the idea of “Africa” as an embracing political identity was established, an inspirational sense of belonging to that identity soon followed, and was swept up into the ways individuals wanted to see and define themselves. This show does a clever job of connecting those conceptual dots. It leaves us with a sense that these studio portraits were far from unassumingly playful local pictures; they actually tapped into much deeper emotional and intellectual flows that were swirling in the air, that asked portrait sitters to thoughtfully consider who they could be. The visual results were consistently and durably powerful, not only due to the very real talents of these photographers, but to the contagious spirit of those who wanted more and imagined themselves differently.

Collector’s POV: Since this is a museum exhibition, there are of course no posted prices. Given the large number of individual artists included, we will forego our usual discussion of individual gallery representation relationships and secondary market histories.