JTF (just the facts): Published in 2020 by Many Voices Press (here). Hardcover, 9.125 x 12.5 inches, 160 pages, with 50 photographic reproductions (45 color, 5 black-and-white). In an edition of 1000 copies. (Cover and spread shots below.)

Comments/Context: About 30 miles west of Memphis and the Mississippi River sits the town of Earle, Arkansas. The population has steadily declined over the last fifty years and now rests at a little over 2,000, of which 90% is African-American. The median family income in 2018 was slightly more than $20,000—and that was before Covid.

Eugene Richards, born in Dorchester, Massachusetts, first visited Earle in 1969 as a 25-year old employee of VISTA (Volunteers in Service to America), the program initiated by the Kennedy administration as the domestic equivalent of the Peace Corps. He did social work in the area and was the photographer for an activist newspaper based in West Memphis called “Many Voices.” For four years, the Arkansas Delta became his base of operations until the newspaper closed, at which time he moved back north.

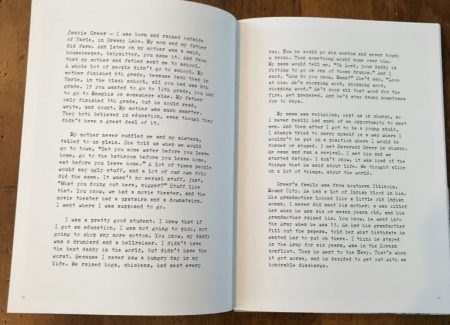

The Day I Was Born concerns his return to Earle in 2019 at the age of 74, fifty years on. The compass of the area is similar to the one he revisited in Red Ball of a Sun Slipping Down (2014, reviewed here), except this time instead of wispy lines of quoted dialogue on the verso to his photographs, he has conducted long interviews with six long-time residents of Earle and interwoven their monologues with his portraits of them and of the homes, businesses, churches, and landscapes they inhabit.

The technique is close to the one he employed in Cocaine True, Cocaine Blue (1994), his chronicle of the crack epidemic in three communities during the early 1990s. The people of Earle are allowed to tell their own stories, many of them harrowing. We should assume what they recite is factual, although one of the themes of the book is memory, never a wholly reliable witness, and the fingerprints of Richards as editor and director are on every page.

Earle didn’t make headlines during the Civil Rights battles of the 1950s and ‘60s. As a woman named Jackie Greer says in the book: “Earle is nothing but a little out-of-the-way place that most people haven’t heard anything about. We never did really get much news coverage. We’re too far from Little Rock. And in Memphis, unless there’s a murder, they hardly holler, didn’t bother about coming.”

African-Americans of whatever station were nonetheless subject to the legacy of slavery and the brutality of Jim Crow. The White and Black sides of town were rigidly segregated, divided by railroad tracks. On a September night in 1971, a protest march through Earle led to shootings and savage beatings by Whites, most of whom were never identified or brought to justice. A woman named Jessie Mae Maples still has a bullet lodged in her back from that night. Although the racial housing lines no longer apply, every person interviewed in the book, whether physically wounded or not, carries the scars of those years.

The title could be the first line of a blues and is a quote from Joseph Perry, Jr.: “The day I was born I was black. You went to a black school. You knew that ‘cause you didn’t go to school with no white folk. There weren’t no white teachers, wasn’t no white nothing.”

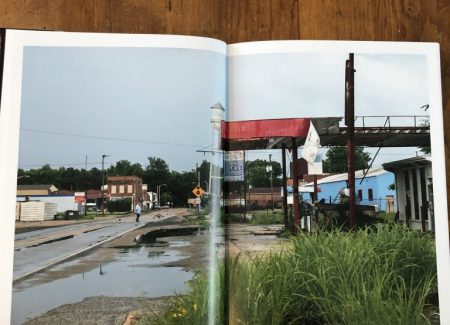

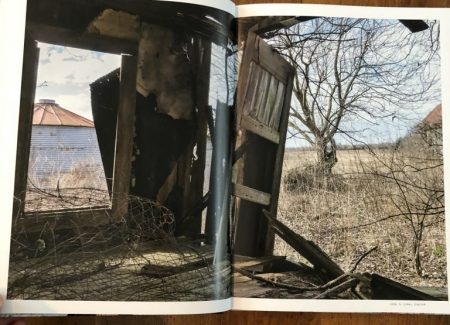

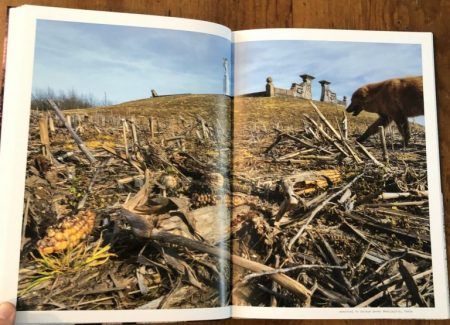

Most of the local businesses that Richards saw in 1969 are gone, along with most of the people. He notes that the clusters of sharecropper shacks once visible every few miles along the roads have all been razed. As Perry observes: “Hope for your children, hope for the future—that ain’t gone, the population gone. ‘Cause what they done, they mechanized the farmer.”

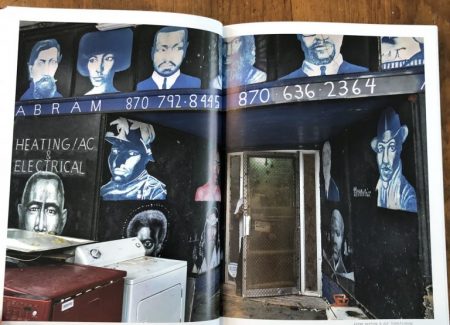

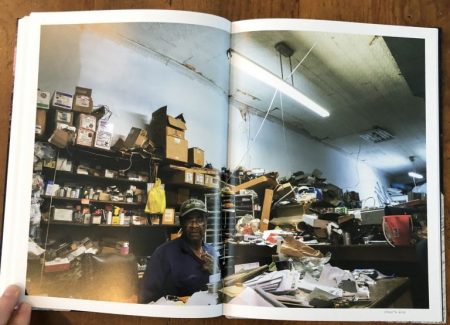

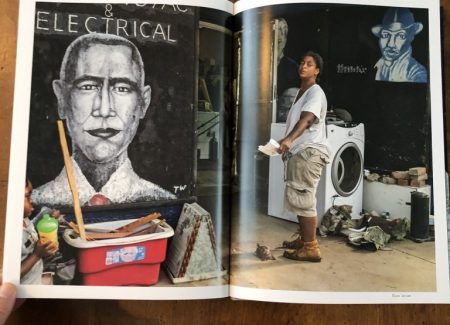

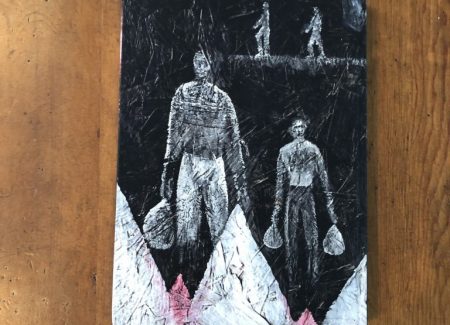

One of the last remaining town landmarks is Abram Heating/AC & Electrical. Located on what used to be the White side of Earle, it is now operated by Stacy Abram, a Black electrician who moved into the building in 1980. On the outside walls, he commissioned a local gay artist, Timothy Way, to paint large black-and-white portraits of Black Jesus, Malcolm X, Angela Davis, Huey Newton, H. Rap Brown, Martin Luther King, Toussaint Louverture, and John Brown. Examples of Way’s handiwork, which also includes portraits of hooded Klan figures and Black laborers carrying bags of cotton, provide the cover art for the book.

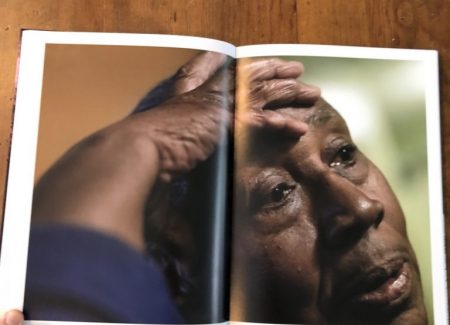

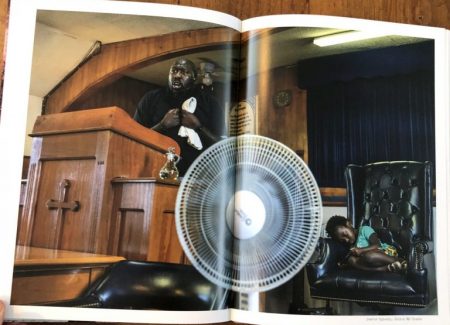

Instead of a topographical view of the town, Richards has opted for an interior one, broken into six separate consciousnesses. He interviewed and photographed Abram inside his cluttered store, Way in his home, where he dresses unconventionally (and perhaps dangerously) in a dress, Maples with a few of her many children and grandchildren. Their stories intersect one another, often when recalling the violence of 1971, with the women, men, and children who worship at the Shiloh Methodist Baptist Church being one of the few common rituals. As each of the six people in the book has a chance to recall his or her upbringing and how the past has shaped their present lives, it’s apparent that each occupies a different Earle in his or her mind. For middle-class readers, it may seem miraculous that despite racism, crime, drugs, spousal abuse and abandonment, this dwindling community has survived to tell the tale.

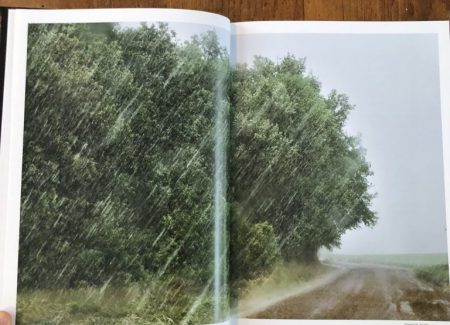

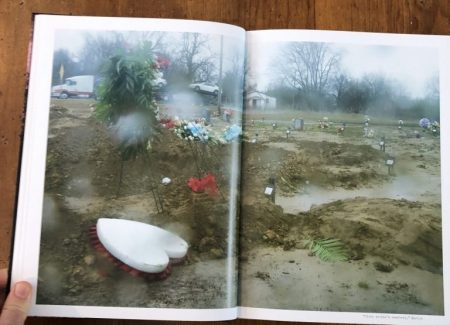

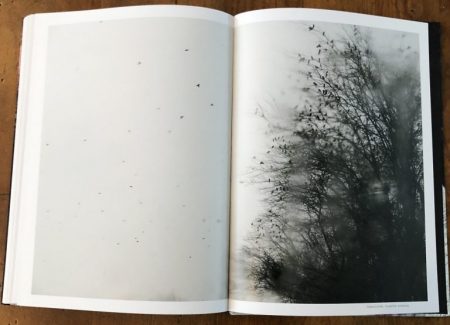

After the age of 60, Richards became as sensitive to landscapes as to people, not that he ever situated one apart from the other. The Blue Room (2008) marked his full capitulation to color and to the idea that time and nature are continually erasing the tracks we’ve scratched on the ground. The new book features several more of these atmospheric portraits: one of a bird flock scattered in the sky above the two-lane highway leading into the perfectly named town of Twist; another of a driving rainstorm as seen through the windshield of his car; and a third of a mud-puddled street in town. It’s a challenge to photograph terrain as flat as this and Richard has met it. His landscapes are reminders that, however fertile the soil of the Delta may be, cotton was picked here for more than a century in torpid conditions of wet, oppressive heat.

The portraits here are not as penetrating or evocative. One consequence of his fragmented narrative, and his engrained tendency to photograph faces in tight close-up, is that Richards seems to be exerting more dramatic control over the lives of his subjects than is healthy, as if he hasn’t allowed them space to breathe.

Both of his recent books feel autobiographical. Outward-looking in their emphasis on verbal testimonies from others, they’re also about keeping faith with his youthful idealism as a social worker and with the values of social documentary as he has inherited and reinterpreted them.

Robert Capa, Carl Mydans, and other photographers of human conflict and misery in the so-called golden age of magazines and newspapers were usually too busy moving between assignments to form longstanding relationships with the people in their pictures. Weegee did not keep in touch with the families who had lost a parent or sibling or child to murder. As quickly as he showed on the scene, he was gone. Once he had the shot he wanted of the dead body or the perp in the paddy wagon, he didn’t look back.

Other photographers—Gordon Parks with the Brazilian boy Flavio da Silva, Mary Ellen Mark with the homeless teen prostitute Tiny—maintained ties or friendships with people they had portrayed years before. Perhaps the most ambitious attempt to document lives over time is the series of Up films, in which Paul Almond and the late Michael Apted have followed seven British boys and girls every seven year since 1964, recording social constancy and catastrophic change as they became men and women. The practice of decades-long documentary is, however, exceptional within the tradition.

Richards’ return to Earle, born from guilt and curiosity, is proof to himself that he did not abandon the people he was enlisted by VISTA to support. Aspects of daily life have undoubtedly improved over fifty years. As Abram says, “People don’t understand, when I was coming up we could be arrested if we assemble on the corner, three or four of us.” At the same time, Richards has to accept the lacerating truth (as much of it as photography and interviews can disclose) that the economic well-being of the people here has not progressed. They tell him so and his photographs confirm their verdict.

Richards belongs to a generation of documentary photographers whose place in the art world was never secure and has become less so. The New York publishing houses that used to decorate their lists with one or two books by non-celebrity photographers a year can no longer afford to be so charitable. Even the few publishers of fine-art photography are not as welcoming as before to traditional humanists. So self-publishing, perhaps boosted by Kickstarter, has become for many the most desirable option for presenting pictures.

The Day I Was Born is self-published and by my count the seventeenth book by Richards. It pushes forward the recent process of circling back to his beginnings. His first book, published in 1973, was Few Comforts or Surprises: The Arkansas Delta, a black-and-white record of his VISTA years. He surely knows that a White northern photographer inserting himself now into the lives of impoverished Blacks in the South, and disclosing their pain and dysfunction, invites charges of cultural exploitation. He did not have to worry too much about these issues in 1973, before the critique of documentary was highly developed in academia. These days, for some theorists only a local Delta photographer of color should take these kinds of pictures. Speaking selfishly, I am glad Richards took the risk.

Collector’s POV: Eugene Richards is represented by Stephen Daiter Gallery in Chicago (here). Richards’ work has little secondary market history in the past decade, so gallery retail likely remains the best option for those collectors interested in following up.

Perhaps our paths crossed at the cross roads. At age 15, I walked in to the SNCC office in Little Rock and joined other VISTA volunteers to march, protest, sit-in, to work. “Sweet Willie Wine” and my brother, Bobby Brown led a march from Forrest City to Little Rock.

Thank you.