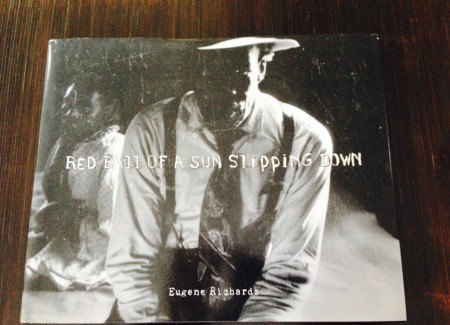

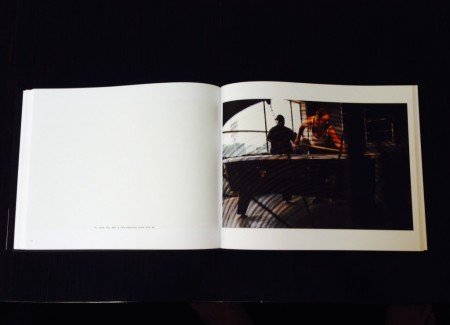

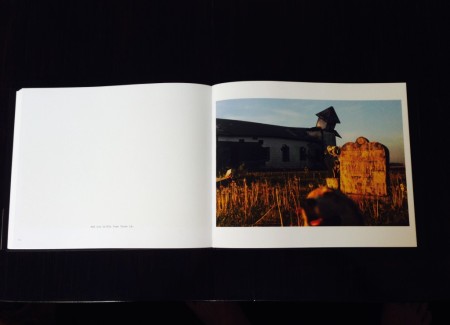

JTF (just the facts): Self published in 2014 by Many Voices Press (no website, original kickstarter here). Hardcover (9 ½ x 11 ¾ inches), 112 pages, with 52 photographic reproductions (26 color, 26 black-and-white). Includes a postscript by the photographer. $50 (Spread shots below.)

Comments/Context: Documenting the lives of the poor and marginalized was once the noblest calling a photographer could answer. The late 19th century tradition begun by John Thomson and Jacob Riis may have peaked during the Great Depression with the associative efforts of the Photo League and the FSA, but it remained vital into the post-war era as W. Eugene Smith, Robert Frank, Tony Ray-Jones, Danny Lyon, Bruce Davidson, Mary Ellen Mark, and others bridged the formerly antagonistic worlds of commercial magazines and art galleries.

Attitudes toward humanistic documentary made a sharp left turn in the 1970s as artists and critics began to wonder if photographs of the dispossessed weren’t ultimately designed to assuage the voyeuristic consciences of a liberal middle-class. In certain quarters of academia, photographers who brought back reports of squalor in foreign lands or from America’s slums were viewed with suspicion, as grandstanders for social justice with a secret agenda as upholders of the status quo. Martha Rosler and Victor Burgin (among others) added sharper rhetoric and analysis to the critique of documentary. For some, the ease with which a camera can turn any stranger into the “other” should make everyone examine what right they have to photograph someone of lower economic station or different ethnic background. (David Levi Strauss’s latest book has a good replay of the arguments.)

For the last 40 years, Eugene Richards has worked as though these sticky issues could be ignored. He is certainly aware of them and in interviews and his own writings has noted the inevitability of being a permanent outsider when recording the lives of people worse off than he.

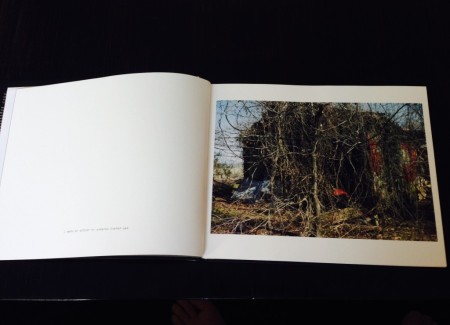

But self-consciousness about the problems of photojournalism has not deterred him from pursuing projects that are squarely within its familiar confines. He has never ventured into the theoretical deep ends of conceptual art. The intertwined impulses that originally moved him to take up photography in earnest in the 1960s, when he was both a student of Minor White and then a health advocate in the South for VISTA, have continued to motivate him. In more than a dozen books of graphic realism, he has interpreted an array of American social concerns in an elegiac mood: the shifting racial character of white working class Dorchester, Massachusetts (his hometown); his first wife’s breast cancer; the grisly routine of an urban hospital’s emergency room; heroin and cocaine addiction in the ghetto; the lives of those who had family members killed at the World Trade Center; and the poignant blight of abandoned houses across the country in the time of the Great Recession.

His newest book (funded by a Kickstarter campaign) is ostensibly a document about the impoverished residents in the place where he worked for VISTA. By combining 20 photographs from his first book, Few Comforts or Surprises: The Arkansas Delta, published in 1973, with others taken on revisits—a handful dating from 1986 and a larger group from 2010—the book is also an autobiographic reflection on the passing of time.

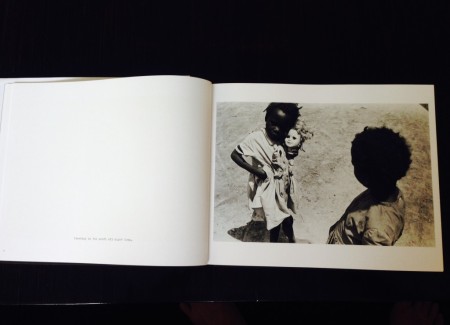

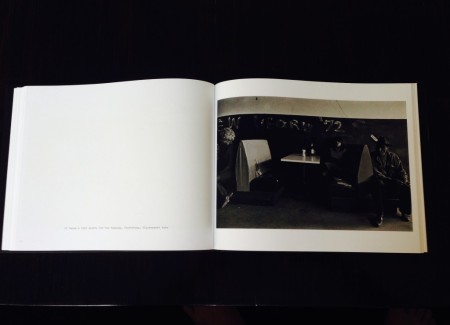

The earlier work here is in black and white, the later in color. It may appear that in the sequencing he has deliberately obscured tell-tale clues that would allow a linear reading—two pictures from 2010 might be followed or preceded by one from 1969—until one realizes that this blurring is less an artistic strategy than a brute economic fact he wants to underscore: that one year or decade can be much like any other for the chronically poor. Despite well-meaning programs like VISTA, generations of families have been consigned to a perpetual cycle of illiteracy and unemployment. The people in Richards’s pictures are African-American and Southern, but the same story could be told about pockets of people in any region of the country.

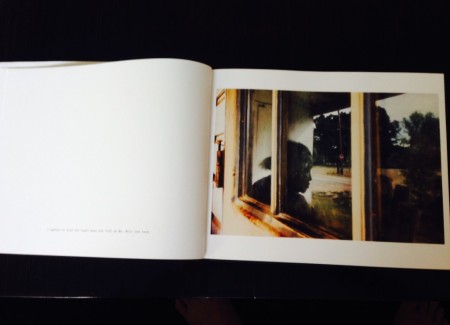

Richards has written a laconic text (set in an old-time typewriter font) that introduces some of the characters and situations he has photographed in this Delta town. Each image on the right-hand page is accompanied by a sentence (or a fragment of one) on the left-hand opposite, the words sometimes concluding in a thought that has been sustained over as many as 20 pages. The narrative is free-floating, with no direct correlation between specific words and a specific photograph.

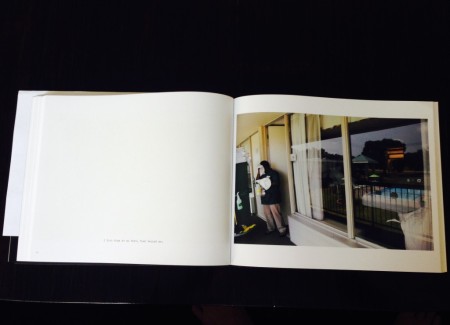

Richards wonders what he thinks he ever accomplished here and questions his own behavior. He admits to not having comforted some of those who told him about their emotional pain. His own mortality (he turned 70 this year) is also an issue in the text. Looking in the mirror back in a motel, he sees how his own bald head and thickened jaw resembles his father’s.

His ambiguous role as a photographer far from home and yet invading the homes of others is noted in a story about a woman named Porter Lee who reluctantly lets him into her ramshackle house.

“She never looked me straight in the eye when we talked./And if we weren’t talking she ignored me,/except to shake her head at me when she thought I was taking/too many pictures of her grandkids.”

When he tells her it’s time for him to leave the Delta, however, she is visibly distressed. They watch a long, slow, violently red sunset with her family on the porch.

“’What you’ll do,’ Porter Lee says, ‘is forget us.”

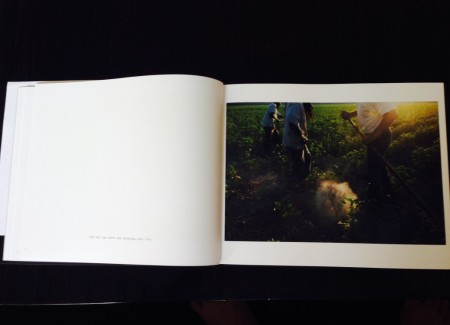

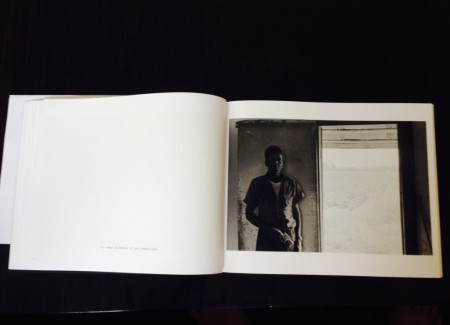

To prove that he hasn’t, and in hopes that we won’t either, Richards has tried to evoke her life and the place she once inhabited in sequences of images that recall David Gordon Green’s films, with their attention to slow Southern rhythms and lush textures. A photograph of a girl holding a doll’s decapitated head is followed by one of three men hoeing a field, a dirt cloud shot through with sunlight. A black snake in a tree is glimpsed at night when its scales shimmer, like a monster in a cave. Children and dogs cavort in a landscape where a road divides fields of tilled crops. A man stands by a doorway, eyes closed, his gnarled hand discreetly holding a pistol.

A monochrome scene from 1971 of a white man on a horse overseeing a black man picking cotton at a prison farm can be contrasted with a 2010 snapshot of a man wiping his brow as he emerges from cleaning a motel room. It is up to us to decide how much progress has been made in this region to make it easier to earn a living. As to the question of what to do to raise up the perennially deprived, these photographs offer no solution.

The burdens of memory and history gradually emerge as the true subject for Richards who writes in a postscript: “As happens whenever you return to the Delta, the space between things that came to pass long years ago and the way it is now begins to collapse.”

The harsh beauty that he has found in this corner of Arkansas is almost enough to make up for the sad truth that the conditions of life as he has recorded them here aren’t likely to improve before his next visit.

Collector’s POV: Eugene Richards is represented by Stephen Daiter Gallery in Chicago (here); an exhibit of this body of work was on view there this past summer (here). Richards’ work has little secondary market history, so gallery retail remains the best option for those collectors interested in following up.

I came here while reading Grif Stockley’s RULED BY RACE: Black/White Relations in Arkansas from Slavery to the Present( see my review of the book on Amazon.com. In any event, Stockley writes about the work of MANY VOICES newletter and I wanted to learn more. This treatment on Eugene Richard’s photography remind me of parts of the book HALF PAST AUTUMN on the legendary photographer, Gordon Parks. Nice Read.