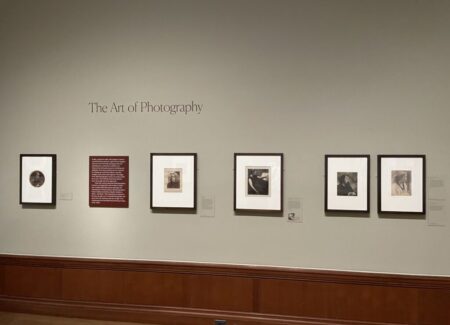

JTF (just the facts): A total of 76 photographs, framed in dark wood and matted, and hung against almond and maroon walls in a divided space on the museum’s main floor. (Installation shots below.)

This touring exhibit was organized by the Victoria & Albert Museum and is drawn from its permanent collections. The installation at the Morgan Library was curated by Joel Smith and Allison Pappas. The show also made stops at MoPA San Diego and the Jeu de Paume in 2023 and the Milwaukee Art Museum in 2024.

The show is divided into thematic sections, as follows:

“The Art of Photography”

- 20 albumen prints, 1864, 1864-1865, 1865, 1865-1866, 1866, 1867, 1869, 1870-1874, 1872, sized roughly 9×11, 10×8, 11×8, 12×12, 13×10, 15×13, 19×15, 20×15, 20×16, 21×15, 23×18, 24×20, 24×22 inches

- 1 carbon print, 1864, sized roughly 22×17 inches

- Henry Herschel Hay Cameron, 1 albumen print, n.d., sized roughly 21×16 inches (portrait of Julia Margaret Cameron)

- 1 Petzval camera lens belonging to Julia Margaret Cameron, 1865

“Pioneering Portraits”

- 21 albumen prints, 1864, 1865, 1866, 1867, 1868, 1868-1872, 1870, 1871, 1872, 1873, 1874, sized roughly 9×8, 12×10, 13×11, 14×11, 18×15, 19×15, 20×15, 20×16, 21×16, 22×17, 24×20 inches

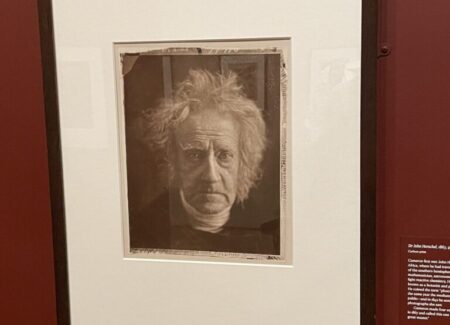

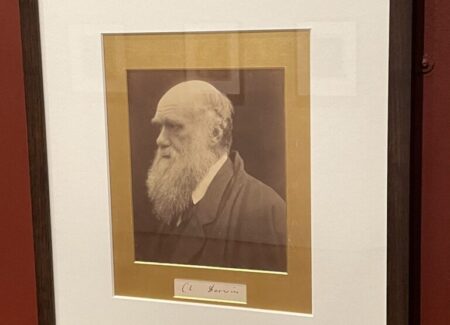

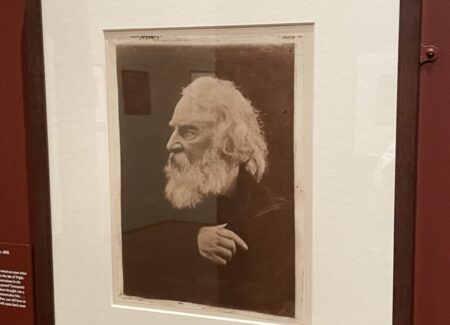

“Famous Men”

- 4 albumen prints, 1865, 1867, 1868, sized roughly 16×13, 17×13, 17×14, 24×20 inches

- 3 carbon prints, 1867, 1868, sized roughly 22×18, 24×20 inches

“Cameron’s Storytelling”

- 11 albumen prints, 1864, 1865, 1865-1866, 1867, 1867-1874, 1868, 1874, sized roughly 10×8, 13×10, 15×11, 20×16, 24×20, 27×22 inches

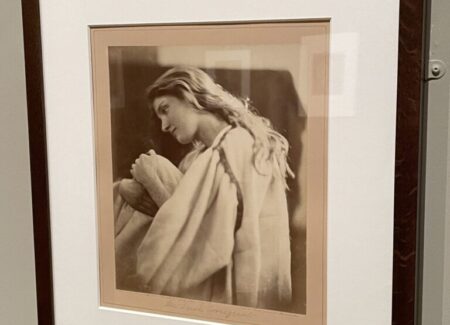

“Cameron’s Heroines”

- 8 albumen prints, 1864, 1865, 1866, 1869, 1870, 1870-1874, 1872, 1874, sized roughly 10×9, 14×12, 18×14, 20×14, 22×17, 23×18, 24×20 inches

- 1 carbon print, 1867, sized roughly 20×16 inches

- (vitrine) 1 leather-bound album with albumen prints, 1875, sized roughly 18×14 inches

“Bible Studies”

- 5 albumen prints, 1865, 1866, 1869-1870, 1872, sized roughly 14×10, 22×19, 23×18, 24×20 inches

“Later Years”

- 2 albumen prints, 1875-1879, 1878, sized roughly 14×11, 20×16 inches

- (vitrine) manuscript pages from the artist’s unfinished memoir, n.d., sized roughly 10×8 inches

A catalog of the exhibition was co-published in 2023 by the V&A Museum and Thames & Hudson (here). Hardcover, 7.4×9.4 inches, 208 pages. Includes essays and image captions by Lisa Springer and Marta Weiss. (Cover shot below.)

Comments/Context: It’s decently hard for us here in the 21st century to reach back some 150 years and to consider what we might have expected from a photographic portrait had we lived in the 1860s. At that time, the medium of photography was still relatively young and experimental – having been invented just two decades earlier – and new and improved approaches were being formulated and commercialized quite quickly. What we can reasonably assume is that to the extent that people were aware of photography at all, the aesthetics of “professional” portraiture at that moment were fundamentally studio based – figures formally posed, standing or seated, and seen from a distance in interior settings (generally with neutral backdrops), lit with even natural light, and documented crisply and with as much clarity as any of the technologies could muster at that time, generally resulting in a small print of some kind.

And if we can try to steep ourselves in those photographic expectations, we might begin to understand just how radical, and indeed almost inexplicable, that Julia Margaret Cameron’s portraits must have seemed when they first appeared. It’s hard to know where to start: the images were big; they were made intimately up close, with heads, faces, and expressions readily visible (and nearly life sized in some cases); the images were often deliberately blurred or darkly shadowed to expressively enhance the desired mood; the pictures were undeniably and in some cases elaborately staged, with poses, costumes, and gestures drawn from paintings, poetry, theater, myth, and the Bible; and in a few cases the photographs were actually made outside. Put all of these factors together and Cameron’s efforts were so inherently different from the established norms of the time that they were broadly dismissed, either as mannered pictorial nonsense or as outright photographic mistakes, a few of her (mostly male) critics sneeringly claiming that she didn’t actually know how to use her equipment properly.

In the many years since, Cameron and her work have been thoroughly reconsidered and reassessed by scholars, critics, and the general public, and her rightful place as a 19th century photographic pioneer and innovator was long ago reestablished. And while a few holdouts might still find her portraits a bit too ethereal and pictorial for their tastes, the vast majority of viewers continue to find consistent grandeur in her elegant expressiveness. After a slow start, Cameron has become an undeniable fan favorite.

But even the best of 19th century photography finds its way into the rotation of shows on view in New York only so often. Solo presentations of Cameron’s work were last seen here more than a decade ago, in a small gallery show in 2011 (24 pictures, reviewed here) and in a somewhat larger museum survey at the Met in 2013 (38 pictures, reviewed here). This exhibit on view at the Morgan Library is far more comprehensive, offering a tightly edited survey of her entire career; drawn from the holdings of the Victoria & Albert Museum in London (which number nearly one thousand Cameron prints), this touring show is likely the best chance New Yorkers will get to examine Cameron’s work in depth without a trip overseas.

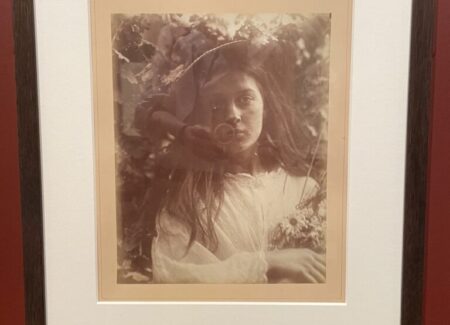

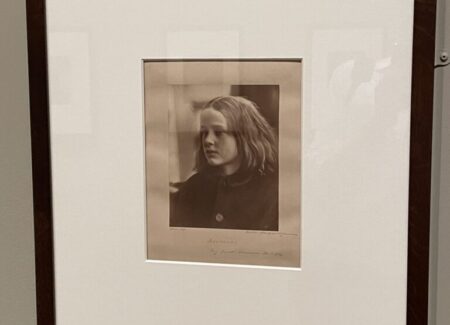

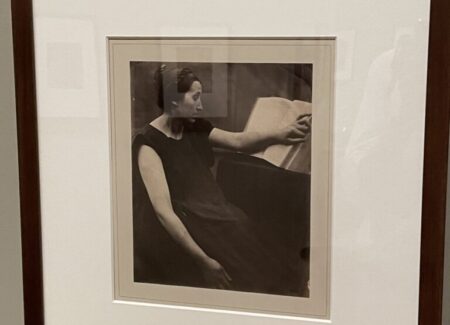

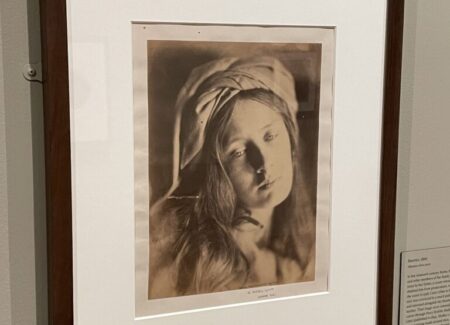

The show has a hybrid curatorial structure, with a loose chronological flow from early to late, particularly in bookended sections at the beginning and end of the installation, with subject matter and thematic groupings in between. The story essentially begins in 1864, with an intimate portrait of the artist’s neighbor Annie, which Cameron called “my first success”. Cameron had been given her first camera a year earlier, when she was 48, and after some initial trial and error, started to find her aesthetic voice as a photographer. Annie is seen from close up, looking down (not into the camera) and seemingly lost in thought, her face gently blurred and her hair wispy and loose; even now it feels resolutely modern and unexpectedly personal, as compared to the typical rigidities of a formal setup. And as a signal of what was to come, the picture undeniably aims us somewhere we hadn’t been before with 19th century portraiture.

While Cameron would in time make a number of images of famous writers, artists, scientists, and others from her larger social circle, for the most part, her subjects and models were those already handy (and thereby willing to pose) – members of her extended family, domestic housemaids, friends, and neighbors. Many of her early compositions were Madonna and child-style arrangements, sometimes using her own grandchildren as the infants, and it didn’t take long for her to bridge out beyond the Bible to other storytelling modes, leveraging the misty evocativeness of poetry and allegory. In her hands, a portrait could of course be a portrait of an actual specific person, but just as often it was a staged impression of someone more archetypal or universal, with her inspiration drawn from some other source.

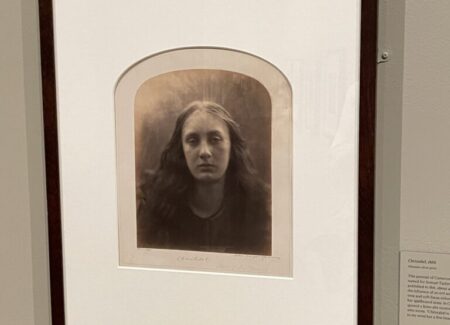

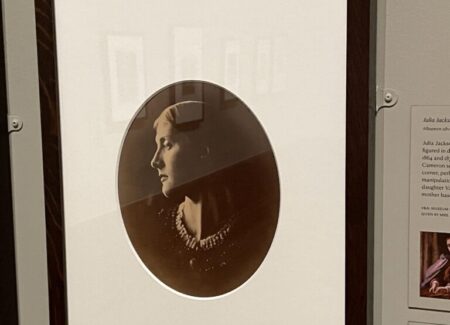

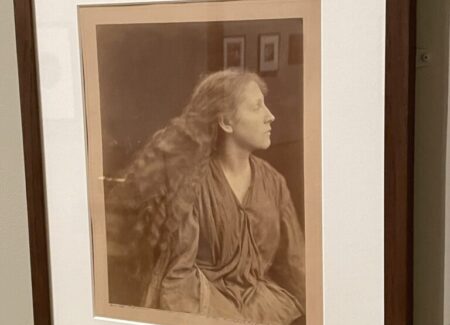

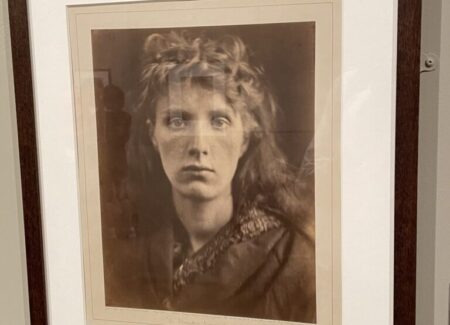

Women (and younger girls) are featured most often in Cameron’s portraiture, and this show offers a knockout parade of superlative female sitters (her “heroines”), one after another after another. What connects these many portraits together is their consistently radiant luminosity and emotional clarity, each face filled with the richness of deeply felt expression, regardless of whether the model was portraying herself (as in the case of Julia Jackson, Mary Hillier, Emily Peacock, May Prinsep, or others) or someone like Sappho, Maud (from Tennyson’s poem), Christabel (from Coleridge’s poem), Elaine (from the King Arthur legend), Gretchen (from Faust’s play), or Isabel (from Shakespeare’s play). Cameron’s soft focus formula was elegantly applied to all of these women (and many more), with the photographer infusing each one with breathtakingly ethereal poise and presence.

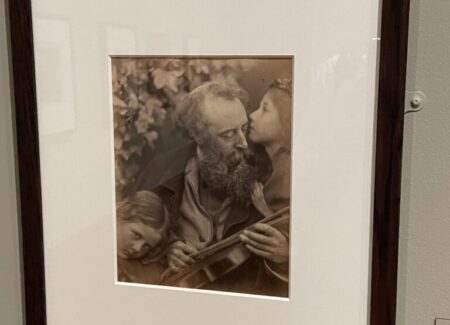

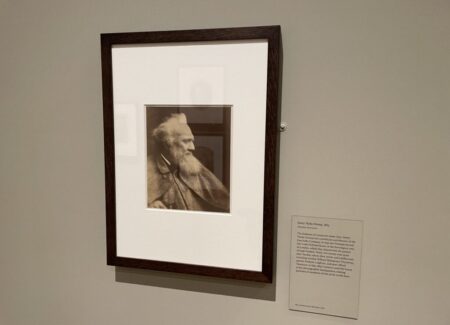

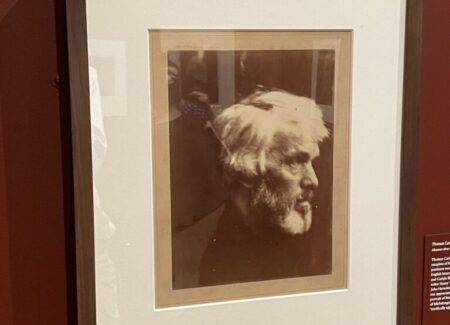

The best of Cameron’s portraits of men use some of these same blurred techniques, shadowed profiles, and cameo-like isolations, but aim them less at creating an aura of “beauty” and more towards encouraging a sense of gravitas and intellectual heft. The heads of Darwin, Tennyson, Longfellow, Carlyle, and Herschel are set against dark enveloping backdrops, allowing us to aim all of our attention at their famous faces, each one seen with imposing intimacy.

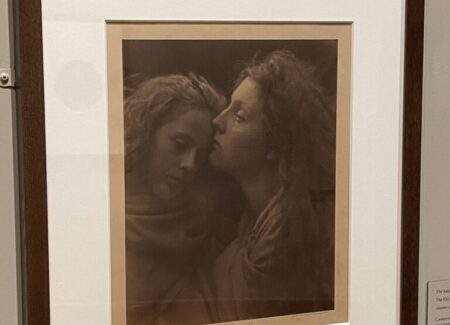

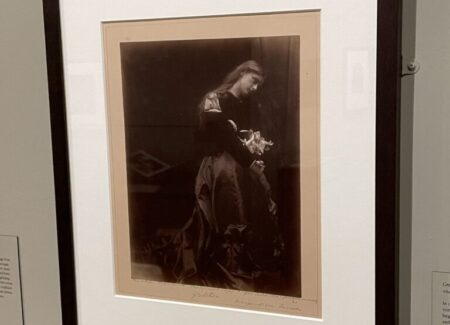

Most of the rest of the works on view move beyond studies of a single individual to groupings of two or more figures, with each additional man or woman expanding Cameron’s storytelling possibilities. Elaborate draped costumes and headscarves, natural props and backdrops, musical instruments, and even a crown or a set of wings or two further embellish these scenes and tableaux, Cameron intricately tuning the aggregation of poses to evoke particular moments or stories. Again, Cameron draws on a range of resonant source material for inspiration, including Bible stories, Arthurian legends, and romantic poems, but each of these tales of saints, virgins, and nymphs is then filtered through her own unique aesthetic, leading to layers of gentle pensiveness, emotional introspection, and beauty not seen in such images before. To my own eye, the narratives and contexts themselves are less important than Cameron’s inspired interpretation of them, with each ruffle of cloth or textural cascade of hair amplifying the innocent grace, lilting wistfulness, or tender sorrow of the chosen moment.

The exhibit ends with a few portraits from Ceylon, where Cameron moved with her family in 1875, and some hand-written pages from her unfinished memoir, but her photographic career was cut short by her death in 1879, just fifteen years after her first photographic success. What’s clear from this finely crafted exhibition is just how ground-breaking her approach to photography was for her times – she is said to have called her camera’s lens (one of which is on view) a “living thing, with voice and memory and creative vigour”, and she seems to have considered herself a collaborator with that spirit. In picture after picture seen here, she’s taking risks, trying out experiments and manipulations, and cutting against the conservative grain of the medium, thereby making room for her own stylized artistic vision. It’s no wonder these pictures were controversial, but it’s also obvious that they were astonishingly imaginative and inventive. That her portraits still connect to us with such intense emotional power and sublime grace is a testament to the durability of her uniquely personal approach.

Collector’s POV: Since this is a museum show, there are, of course, no posted prices. Cameron’s work is intermittently available in the secondary markets, with prices in the last decade ranging from roughly $2000 for faded, lesser known images to over $460000 for her most iconic portraits.

I wasn’t expecting this review to be so unexpectedly compelling.

Thanks for making me look again.