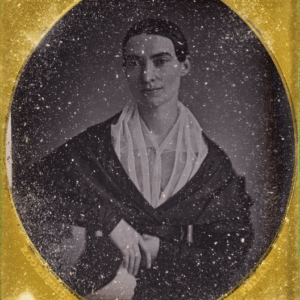

JTF (just the facts): A total of 38 black and white photographs, framed in dark wood and matted, and hung against tan colored walls in a series of three interconnected rooms on the second floor of the museum. All of the works by Cameron are albumen silver prints, made between 1864 and 1874; the exhibit also includes 2 glass cases displaying single pages of larger albums. While nearly all of the works on view were taken by Cameron, the first room includes a sampler of related works by Oscar Gustav Rejlander (2 albumen silver prints, 1863-1867), William Lake Price (1 albumen silver print, 1857), David Wilkie Wynfield (2 albumen silver prints, 1863), and Henry Herschel Hay Cameron (1 albumen silver print, a portrait of Cameron (image below), 1870). All of the works come from the museum’s permanent collection.

Comments/Context: This smartly edited Julia Margaret Cameron sampler comes along at an opportune time in the ongoing photographic discussion, at a moment when many contemporary photographers are considering both the limits of staging and the complicated issues of effects that change the mood of an underlying image. That a 19th century portraitist could be so relevant to the current photographic dialogue says something both about Cameron’s staying power as an artist and about the recurring nature of some of these boundary defining issues for the medium. Her work is as powerful as ever, and her unorthodox-for-the-times use of set-up scenes and soft focus blurring seem surprisingly innovative, given what we know now about the subsequent evolution of the art form.

This small selection of works doesn’t break any new ground in the academic understanding of Cameron’s photography, but it does faithfully tell her artistic story with portraits of celebrated thinkers and writers, allegorical images of the women of her household, and groups of friends and relatives in staged Shakespearean and biblical scenes, all drawn from the Met’s permanent collection. The men in her portraits tend toward the grizzled and quietly brilliant: Sir Thomas Herschel emerging from the darkness, his wispy hair and hypnotic eyes staring out with authority, or Alfred Lord Tennyson reading a book or wearing a frilly lace collar, his stringy hair and long beard giving him an air of mysterious romance. Cameron’s women run the spectrum from angelic and ethereal to bluntly proud and stoically confrontational, all breathing with the wide-eyed freshness of life. Embroidered hats and patterned dresses help characterize Zoe, Maid of Athens and Sappho, while wild greenery, loose hair and an artfully held calla lily give context to Pomona and May Prinsep. Cameron’s allegorical scenes go further in their overt storytelling, running the gamut from Lear to Lancelot, with a spiritual and religious subjects like the Annunciation and the Madonna thrown in for good measure.

If Cameron’s portraits were simply dreamy and poetic, they would probably have been forgotten long ago as relics of the Pre-Raphaelite era. What makes them modern is their seething energy, their immediacy of experience; a great Cameron portrait (and there are a handful on display here) grabs you by the throat, pulling you into a penetrating stare that seems ready to swallow you up. These people, however contrived and costumed, seem for just that moment to be right before you, alive and slightly unpredictable. By allowing the rest of the frame to drop into a blur (using long exposures and slight movement), the viewer’s attention is drawn straight into the sitter’s eyes, where we find a startling array of subtlety and emotion. Few photographers in the some 150 years since these portraits were taken have made this visual connection between viewer and viewed with more consistent power and grace.

While this show certainly succeeds in bringing Cameron back to the top of our minds, what we need now is an exhibit that explores the enduring legacy of Cameron, one that traces stage setting and persona creation all the way back to her beginnings and all the way forward to their contemporary echoes. My bet is that she’s been more influential than we generally give her credit for; while we can all revel in the wonder of her best portraits, we are likely underselling her more conceptual impact on downstream generations. Cameron disregarded her critics and made photographs that have stood the test of time; we owe it to ourselves to follow the breadcrumbs back and see how her ideas have permeated the medium.

Collector’s POV: Since this is a museum show, there are, of course, no posted prices. Cameron’s work is intermittently available in the secondary markets, with recent prices ranging from $1000 for faded, lesser known images to nearly $250000 for her most iconic portraits.