JTF (just the facts): A total of 101 color and black-and-white photographs, without mats and unframed, mounted under glass directly on the museum’s walls. Of the photographs, 60 are gelatin silver prints of shots taken between 1988 and 2016 (the print date is often many years after the image date); they range in size from roughly 7×5 to 44×31 inches (or the reverse). There are 41 dye transfer prints of pictures taken between 1998 and 2006; of these, 40 measure 20×16 inches and one measures roughly 30×20 inches.

In addition to photographs, the exhibition also includes the following works:

- I want a president, 1992, typewritten text on paper, 14 × 8 1/2 inches.

- The Fae Richards Photo Archive, 1993–96, gelatin silver prints and chromogenic prints with typewritten text on paper, dimensions variable. Photos range in size from 3 3/8 x 3 3/8 inches to 13 7/8 x 9 7/8 inches.

- Strange Fruit, 1992–97, orange, banana, grapefruit, lemon, and avocado peels with thread, zippers, buttons, sinew, needles, plastic, wire, stickers, fabric, and trim wax, dimensions variable.

- Robert, 2001, ten suitcases, 72 7/8 × 21 1/2 × 20 inches.

- 1961, 2002–, suitcases, dimensions variable.

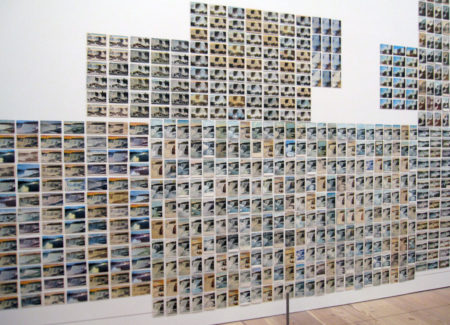

- You see I am here after all, 2008, 3,883 vintage postcards, 11 feet x 10 1/2 feet x 147 feet.

- Survey, 2009–12, 6,266 postcards and table, dimensions variable

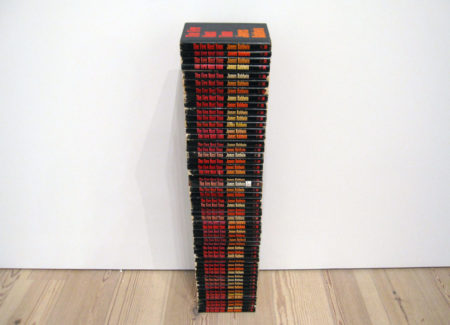

- Tipping Point, 2016, 53 books (James Baldwin, The Fire Next Time, first edition, Dial Press, New York, 1963), approximately 38 x 8 x 5 1/2 inches.

- How to Take Good Pictures, 2018, approximately 1,050 books, 30 1/2 x 5 7/8 x 324 inches.

- Homage, 2018, screenprinted text on office walls throughout the museum, dimensions variable.

(Installation shots below.)

A companion catalogue published by Prestel (here), with essays by Douglas Crimp, Elisabeth Lebovici, Fred Moten, Elisabeth Sherman, Bennett Simpson, and Lanka Tattersall, is available. (312 pages, 207 color illustrations, $60 hardcover.)

Comments/Context: In 2008, Zoe Leonard arranged nearly 4000 souvenir postcards of Niagara Falls on a wall at Dia: Beacon, grouped into blocks according to vantage point, starting from one side of the falls and moving from left to right around it. Printed between the late 1800s and the 1970s, the cards vary in color and quality, lending the whole a watery shimmer. Some of the cards bear handwritten messages, one of which, “You see I am here after all,” is also the title of the work. Although it’s made up of pictures, the installation is not a picture. It’s a diagrammatic representation of a place that also functions as a diagrammatic representation of the act of looking.

In this fine-drawn survey, You see I am here after all (2008) occupies a long gallery that links the beginning of the show to its end. Functioning both figuratively and literally as a through line for the exhibition, the piece embodies the constants in Leonard’s work: its themes of survival and redemption; its mapping of geographic, cultural, and personal terrains; and its insistence on the subjective view of the artist, whose unseen, observing presence is surely the “I” of the installation’s title.

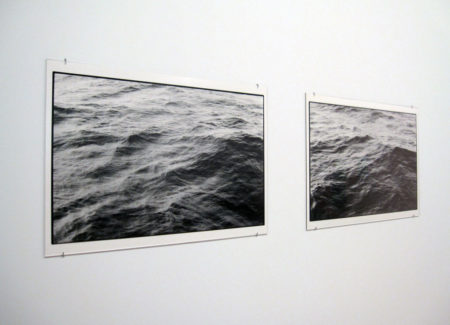

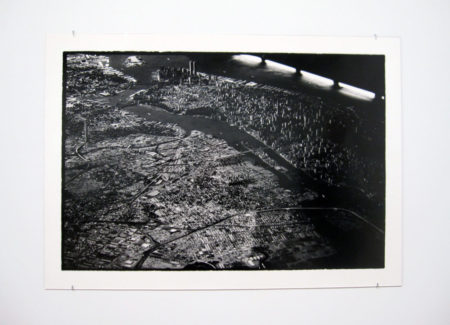

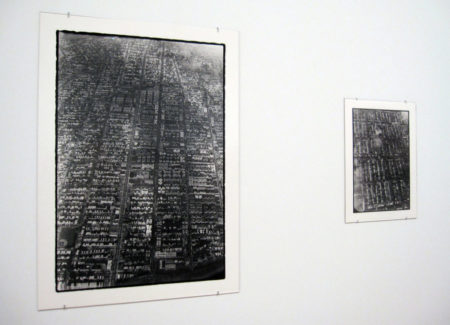

Leonard, who was born in 1961, is best known as a photographer, and the show opens with a selection of black-and-white photographs taken in the 1980s. Uncropped—as are all of Leonard’s pictures—these are mostly aerial views that play with scale and perception. Two images of choppy water with no reference points as guides could have been taken from any distance, or even out of a book. Thin clouds drifting over a vast cityscape give a sense of its true size; a row of fluorescent light tubes illuminating the miniature panorama of New York City at the Queens Museum, do the same thing, though it takes a moment to figure out what they are.

The frame of the airplane window appears in the last of these images, decisively situating the artist in time and space: in that seat, on that plane, at that moment, photographing for no one’s interest but her own. Nearby, running down the center of the gallery, is a 2002 sculpture consisting of a line of used blue and bluish-green suitcases, the number of which will always correspond to the artist’s current age. It’s another reminder of Leonard’s physical presence; another kind of diagram.

By 1990, Leonard, who is gay, had become deeply involved with the queer women artists’ groups Gang and fierce pussy, as well as the advocacy group AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power (ACT UP). (A side gallery contains 300 empty fruit peels, dried and mended with thread, Leonard’s memorial to her friend David Wojnarowicz, who died in 1992 of AIDS-related causes.) In her art, she shifted her attention from physical spaces to the societal, cultural, and political systems that exercise control over the bodies of individuals and concepts of what is “normal.”

Her works made in the early 1990s included photographs taken in medical, science, and natural history museums. Here, several studies of early anatomical models of women—one wears an incongruous string of pearls—join a picture of an iron chastity belt and a set of five pictures of the head of a bearded woman preserved in a jar. “With five images of her in a row,” Leonard told Anna Blume in a 1997 interview, “I wanted to slow people down enough so that they would begin to question her presentation rather than her appearance.”

A vitrine in the same gallery contains Leonard’s extraordinary project The Fae Richards Archive (1993–1996), conceived in collaboration with filmmaker Cheryl Dunye. Wishing to make a film about a fictional gay, black actress and singer of the 1930s, Dunye asked Leonard to create a body of photographs documenting her protagonist’s career. Researching photographic conventions of the 1920s through the 1970s and working with a cast (including Lisa Marie Bronson as Richards), Leonard came up with an eerily convincing record—presented through snapshots, film stills, and publicity photographs—of the performer’s life and loves. Though Richards never existed, this work, like Leonard’s photographs of the bearded woman, seems an act of reclamation.

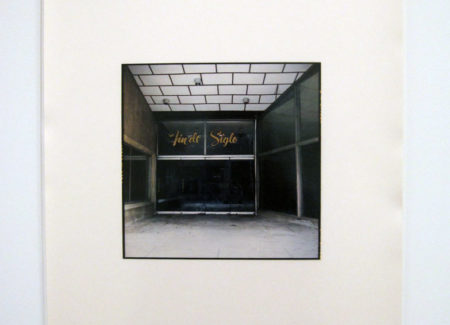

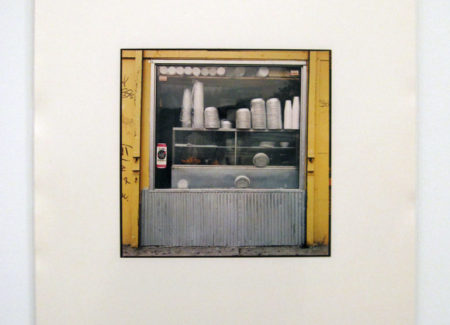

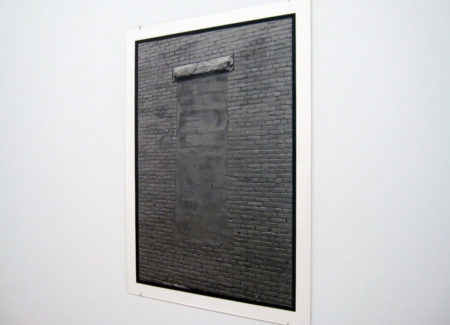

Where this show—which was curated by Bennett Simpson and Rebecca Matalon of the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles—most brilliantly succeeds is in illuminating the emotional power that underpins Leonard’s characteristically muted photographic work. Leonard came of age as an artist at a time when the appropriation strategies of the Pictures generation were giving way to a more political, and even sentimental, art focused on identity, personal narrative, and the body. Contextualized in the show through their pairing with her typed—and once again timely—1992 manifesto I want a president (which begins “I want a dyke for president”) and mid-1990s photographs of such bathroom graffiti as “Gay + Proud + Dead,” Leonard’s unassuming pictures of shabby neighborhood businesses—tailors, clothing stores, bodegas, and the like—in New York and elsewhere, and city trees growing through and around the fences meant to contain them become images not just of tenacity, but of impassioned engagement and sustained resistance.

The relevance of these works to our present moment is underscored, rather too obviously, by the inclusion of two recent sculptures made from stacks of old hardcover books. A tower made from 53 first edition copies of The Fire Next Time, James Baldwin’s 1963 treatise on black identity and the state of race relations in America, broods in one gallery. Spanning another gallery, a row of piles of the Kodak publication How to Make Good Pictures, one pile for each year the book has been in print, seems to trace through sunny cover images a history of a willed indifference to the suffering of others.

More affecting is the group of 2016 photographs that closes the exhibition: studies of family photographs showing Leonard’s mother and grandmother arriving in New York Harbor after leaving Poland nearly a decade earlier. These women, too, were survivors—most of Leonard’s maternal family, who fought against the Nazis during WWII and died doing so—and Leonard emphasizes her connection to them by bringing them into the space she occupies as photographer: rather than simply reproducing the pictures, she has placed the original prints on the floor of her studio and photographed them from above.

My own mother, who grew up in a speck on the map in the Canadian Maritimes, told me once that as a child she ate Nabisco Shredded Wheat every day for breakfast, propping the box in front of her so she could lose herself in its picture of Niagara Falls, for her a potent symbol of a bigger world and a bigger life. By age 16, she’d be gone from that place and on to that bigger life, but she didn’t reach Niagara until our last road trip together. Looking at Leonard’s installation of postcards, I thought how my mother would have adored it. Because after all, all the people we’ve ever loved are still here.

Collector’s POV: Zoe Leonard is represented by Hauser & Wirth (here). Her prhotographs have been only intermittently available in the secondary markets in recent years, with not enough public transactions to chart a useful price history. As such, gallery retail likely remains the best option for those collectors interested in following up.

Really nice exhibit