JTF (just the facts): A total of 21 black and white photographs, matted and hung in white wooden frames in the main gallery as well as the smaller East room. All of the works are gelatin silver prints, and the show is divided between 15 self-portraits made in 2014-2015 and 6 portraits from 2010- 2014. Physical sizes range from 23 ½ by 16 ¼ inches to 39 x 32 1/2 inches, and all of the prints are available in editions of 8. In five of the prints, the image is flush to the edges of the paper; in all of the others, the image is 4 inches smaller than the paper size. (Installation shots below.)

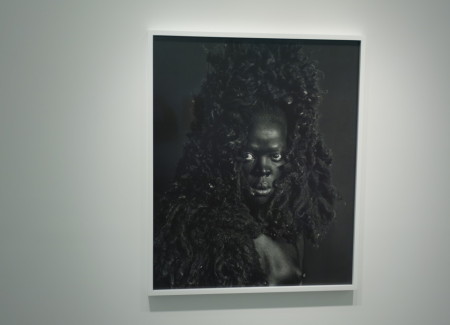

Comments/Context: “Somnyama Ngonyama,” the title chosen by Zanele Mulholi for this show of self-portraits, means “Hail, the Dark Lioness” in her native Zulu.

The commandment is apt. The photographs mix a fierce pride in her artistic identity as a South African and as a woman, with just the right pinch of self-deflation. Clearly aware that she is a beautiful creature, with dark, lustrous skin and a taut, feline body that she is not afraid to expose without clothes, she also knows that the self-portrait is a social construct as well the product of improvisational whimsy. Part of the fun of the series is that place and circumstance have partly dictated how she would portray herself. One has the feeling that she would wake up without a program and let her daily mood—and whatever local props were available—shape what role she would assume—European aristocrat, Zulu queen, coal miner, nurse, super-model. As with self-portraits by Cindy Sherman and Nikki S. Lee, she stands before us as a performer, playing with our expectations and the cultural norms that surround us.

Each of these 15 examples dates from the last two years as she was traveling from her home in Johannesburg to Europe, the U.S., or to other cities in South Africa, either on assignment or to give lectures as an activist or to attend exhibitions of her increasingly celebrated work.

The titles include a word or phrase in Zulu along with the place where the photograph was taken. In Somnyama IV (Oslo), she wears a dark towering wig of cascading curls and nothing else. The stereotype of male privilege familiar from portraits of 17th century European grandees, perhaps Louis XIV or Charles I, may be complicated by the sight of her naked breast, but the intensity of her stare is no less domineering than theirs might be in paintings by Rigaud or Van Dyck. Even without a hairpiece in Somnyama III (Paris), her head is nonetheless almost sinking into a pair of neck pillows. Arranged and printed dark so that they resemble luxurious contemporary fashion accessories, perhaps an update of the ruffs worn by Rembrandt’s women, the items in this context also evoke other cultural associations, with African neck-stretching jewelry and the slave collar.

Most of the set-ups are plain. In Zodwa (Paris), she stands against a black background, nude again except for a necklace of cowries. Multivalent objects with a long history in African culture, worn to symbolize everything from female fertility to the vast power of the ocean, and sometimes used as currency, the shells seem to offer her scant protection. (The title is translated as “Alone” and her expression is one of alienated solitude. )

In some cases the meanings behind a self-portrait are easy to decipher. Thulani, which means “Silent,” shows her in the hardhat of a miner, a notoriously poor and exploited group in the South Africa economy and one that in this self-portrait she presumably hopes to give a voice. Zibuyile, which means “Return,” was photographed in Parktown, a suburb of Johannesburg. The Brancusi-like tower of her own hair that she wears atop her head, and her look of self-possession, may indicate a gratitude about being back in South Africa after a long time away.

In other instances, though, the clues are harder to follow. In Thembeka I, which means “Honest,” she has draped herself with a white cloth, wearing it like a mantilla. Is her furtive expression supposed to be a more “honest” version of herself than she usually permits?

Babhekile, which means “See,” features her turned three-quarters to the camera, again in a white headdress, this time against a background painted with expressionist brushstrokes. The title’s imperative mood suggests she is issuing another command, but the Oslo location doesn’t offer enough evidence for me to make a confident guess what she may be wanting to convey.

The gallery press release describes Muholi “as a visual activist confronting the politics of race and pigment in the photographic archive….<who> strives to exorcise the culturally dominant images of black women that infiltrate media today.”

I don’t know what exorcism she has in mind so I can’t judge if she has successfully accomplished her mission. Nor can I tell what the “culturally dominant images of black women that infiltrate the media today” might be. Can images of black women in any way be called “dominant”? Middle-class or working-class black women are flagrantly underrepresented on the news except as crime victims, and even wealthier black women are largely invisible unless, of course, they’re Michelle Obama or Beyoncé.

Muholi has purposefully darkened her own skin in the printing of her photographs and is quoted as believing that, by adopting this exaggeration, “I’m reclaiming my blackness, which I feel is continuously performed by the privileged other. My reality is that I do not mimic black; it is my skin and, the experience of being black that is deeply entrenched in me.”

I’m not sure what the phrase “I do not mimic black” might mean. But by making herself as purely dark as the gelatin-silver process will allow she may be trying a jiu-jitsu move, harnessing an oppressive prejudice for her own ends. A double negative in logic is, after all, a positive. The tendency of the American media for decades was to darken the skin of black men accused of crimes, the Time magazine cover in 1994 of O.J. Simpson’s mug shot being the most famous example. Reclaiming blackness has been a trend for years in the fashion industry, where the Kenyan model Ajuma Nasanyana was a muse for Vivienne Westwood. Dark-skinned models, though, remain shamefully underemployed on the catwalks of Europe and New York and by the top fashion magazines.

Luckily, Muholi is a better artist than she is a rhetorician. When she garbs herself with funky props, such as headdresses of clothes pins or scouring pads, she brings to mind the portraits by Hendrik Kerstens. The Dutch photographer dresses his female models in similar regalia (plastic bags and toilet rolls) that blend humor with dignity. Muholi’s finest self-portraits hit this same sweet spot.

The six examples in the gallery from Muholi’s Faces and Phases series, published last year in a book by Steidl, are part of a comprehensive project to document black LBGTI individuals in South Africa and beyond. (One of portraits here was taken in Los Angeles.)

As with her self-portraits, she restricts herself to the middle-distant, half-length view. Much as I would like to see what she could do at full-length, her eye for small details of expression, posture, dress, background, and skin tone is that of a caring and a meticulous artist. Personalities emerge within a format that unites each of them into a community.

No one should fear the black lioness after seeing this show, nor is she asking us to bow down to her. But Zanele Muholi deserves to be hailed as one of the most talented portrait photographers working today.

Collector’s POV: The works in this show are priced between $6200 to $7000. Five images have already sold out their editions. Muholi’s work has little secondary market history at this point, so gallery retail remains the best option for those collectors interested in following up.