JTF (just the facts): A group show consisting of 46 black and white photographs made by 9 photographers, framed in black and matted, and hung against white walls in the divided gallery space and the adjacent elevator lobby.

The following photographers have been included in the show, with details on the number of works on view, their processes, and their dates as background:

- Lourdes Almeida: 4 gelatin silver prints, 1992, 1994

- Lola Álvarez Bravo: 4 gelatin silver prints, 1940/later, 1946/later, 1940s/later, 1954/later

- Flor Garduño: 8 gelatin silver prints, 1986/later, 1987/later, 1991, 2013, 2014, 2015

- Kati Horna: 4 gelatin silver prints, 1933, 1956, 1962

- Graciela Iturbide: 7 gelatin silver prints, 1981/later, 1988, 2005, 2006, 2008, 2011

- Cristina Kahlo: 4 gelatin silver prints, 2007, 2011

- Tina Modotti: 3 platinum prints, 1924/later, 1926/later

- Colette Urbajtel: 6 gelatin silver prints, 1976-1978/later, 1979/later, 1988/later, n.d.

- Mariana Yampolsky: 6 gelatin silver prints, 1962, 1987, 1989, 1991, 1991/later, n.d./later

A catalog of the show is available from the gallery for $50. (Installation shots below.)

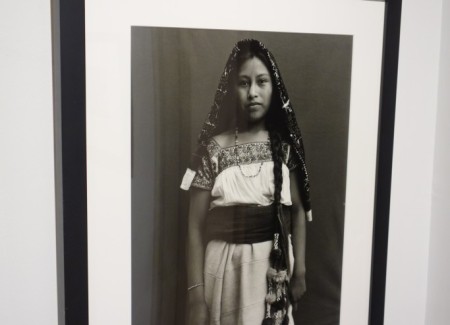

Comments/Context: While the shorthand history of Mexican photography is often reduced to a single (male) name – Manuel Álvarez Bravo – this survey show seeks to rectify that gross oversimplification by introducing the work of a diverse group of female photographers. Spanning nearly a century of artistic activity, from the politically minded 1920s Modernism of Tina Modotti to brand new work by Flor Garduño, the images on view offer a broader and more nuanced look at how different generations of Mexican women have engaged with both the medium and the cultural environment around them.

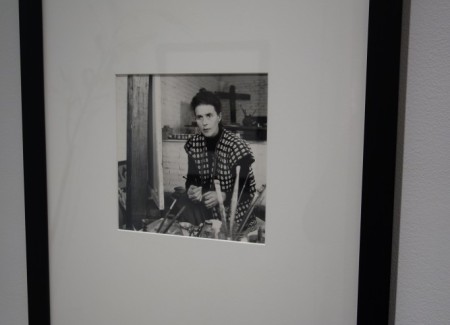

This exhibit isn’t organized either chronologically or grouped tightly by individual photographers. Instead it highlights a more intermingled, communal whole, bringing the contextual themes and commonalities between the works to the surface rather than following a more narrow investigation of each photographer’s isolated contributions. This approach reinforces the idea of a native Mexican photographic bloodline (not drawn directly from Weston, Strand, or other outsiders), a thickly reinforced connection that runs from Tina Modotti to Manuel Álvarez Bravo and on to his wives (Lola Álvarez Bravo, Colette Urbajtel), his many students/assistants (Graciela Iturbide, Mariana Yampolsky, Flor Garduño) and the larger artistic community (including the parallel Frida Kahlo artistic heritage, in the form of Cristina Kahlo). It makes an argument for the continuity, revision, and evolution of a core set of photographic ideas and aesthetic principles that have deeply soaked into the foundations of Mexican photography.

A strong sense of formalism as applied to local subject matter appears again and again across this sampler. Modotti’s worker’s hands resting on a shovel sets the overall tone, which is reinforced by Yampolsky’s village study of high contrast light and dark and Urbajtel’s whitewashed corner with gourds and sticks. Still life clarity also recurs and is extended, starting with Yampolsky’s up close desert plant forms and moving to Iturbide’s ice cart and Garduño’s sensual custard apples.

A healthy dash of everyday dream-like Surrealism is also a common theme. Iturbide’s cemetery is overrun by a swarm of dark birds, Urbajtel’s white drapery is punctuated by inexplicable animal hooves and reaching arms, and Kati Horna’s mysterious staged interiors combine a mask, a candle, and the artist covered in black. Garduño’s recent images hit this theme repeatedly, turning her earlier use of female nudes and lizards toward more symbolic optical metaphors found in the city – vigilant eyes in the sky, candidates reduced to empty outlines, and a mural with eyes crossed out and replaced by a single all-seeing eye in the forehead.

And virtually all of these woman have embraced traditional Mexican culture and folklore as a richly relevant subject. Lourdes Almeida has made portraits of women and girls in towering feathered headdresses and elaborately embroidered ponchos. Kahlo has documented regional brass bands and carnival goers. And many have touched on the presence of various forms of religion, in the form of white robed burials (Álvarez Bravo), virgin statues (Iturbide), and hand crafted dolls (Horna). In this category of imagery, simple pleasures like games with stones (Urbajtel) and the loving caress of a mother (Yampolsky) are just as resonant as any of the more controversial or urgent topics.

Seen together, this spectrum of perspectives gathering fills in many of the gaps in the usual short form history of Mexican photography, adding a more layered female viewpoint to a usual narrative. While each photographer represented here has her own distinct voice, there is still a strong sense of common purpose, converging ideas, and communal support. These pioneering women all broke down countless barriers to pursue their art, and yet seemingly worked together collectively to further define an unique Mexican photographic identity.

Collector’s POV: The works in this show are priced as follows, by photographer:

- Lourdes Almeida: $2500, $3000

- Lola Álvarez Bravo: $6500 each

- Flor Garduño: $4000, $4500, $5000

- Kati Horna: $15000 each

- Graciela Iturbide: $4000, $4500, $5500

- Cristina Kahlo: $2500 each

- Tina Modotti: $10000, $15000, $20000

- Colette Urbajtel: $3500 each

- Mariana Yampolsky: $4500, $5000, $5500, $6500

Of these photographers, Tina Modotti’s work has the most robust secondary market, with recent prices ranging between $5000 and $485000.