JTF (just the facts): A total of 27 black-and-white and color photographs, variously framed and matted and hung against light almond walls in the main gallery space and the book alcove. (Installation shots below.)

The following works are included in the show:

- 10 gelatin silver prints, 1977/later, 1978/later, 1986/later, sized roughly 10×14, 14×19, 18×25, 20×30, 20×48 inches, in editions of 6+2AP

- 8 dye transfer prints, 1983/1989, 1986/1989, sized roughly 13×17 inches, in editions of 15+5AP

- 3 chromogenic prints, 1983/later, 1987/later, sized roughly 22×25, 22×26, 22×28 inches, in an edition of 6+2AP

- 3 chromogenic prints, 1973, sized roughly 3×4 inches, in editions of 12+2AP

- 1 set of 2 chromogenic prints, 1983/later, each sized roughly 43×53 inches, in an edition of 6+2AP

- 2 Cibachrome prints, 1983/c1983, sized roughly 11×13 inches, unique

Comments/Context: Given that photography and filmmaking are both camera-based artistic mediums, it’s not at all surprising that there is at least some overlap between both the functional and the aesthetic aspects of the two. And as a result, we find plenty of photographers who make short films and videos, and a smaller number of film directors (and actors) who make fine art photographs, the transition from single still frame to more continuous time-based movement and back offering opportunities to extend (and limit) “cinematic” storytelling in different ways.

For cinephiles, the German director Wim Wenders likely needs very little in the way of introduction. Back in the 1970s, Wenders was one of the leaders of the New German Cinema movement (along with directors Rainer Werner Fassbinder, Werner Herzog, Volker Schlöndorff, and others), with low-budget variations on the wandering road movie like his Alice in the Cities (in 1974). His most famous film is likely Paris, Texas (from 1984), but Wenders has been consistently productive (and innovative) for decades, with his most recent effort Perfect Days nominated for the Best International Feature Film Oscar in 2024.

While the Dutch cinematographer Robby Müller was behind the camera for most of Wenders’ films in the 1970s and early 1980s, what is perhaps less well known is that Wenders himself used still photography as a way to consider potential locations, settings, and light conditions long before shooting ever began. What perhaps started as a kind of visual note taking eventually evolved into a more consistent artistic practice, and throughout the 1970s and 1980s, Wenders made photographs, in both black and white and in color, as an adjunct or support to his film making endeavors and as engaged everyday seeing during his travels and promotional tours.

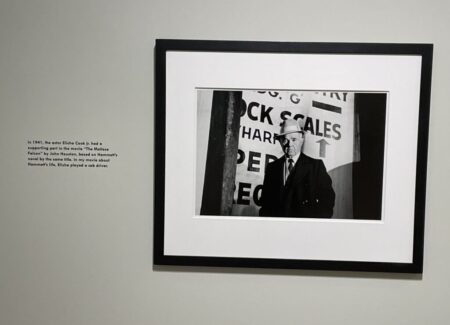

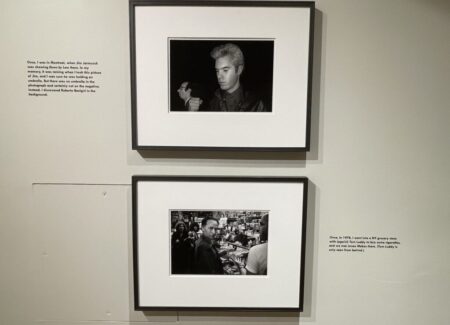

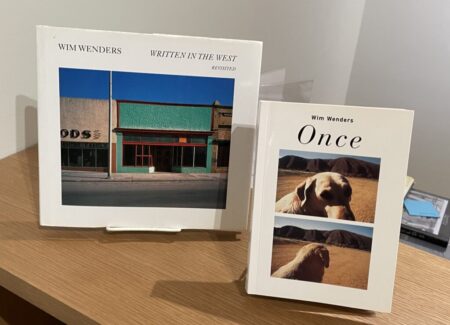

This tightly-edited survey of Wenders’ photography centers on two notable bodies of work, that ultimately took shape as the photobooks Once (from 1977-1984) and Written in the West (from 1983-1987) (cover shots above); the title of this gallery show “Written Once” is reflection of that duality. The black-and-white images from Once are like small visual vignettes from Wenders’ life, populated by famous faces from the film world which make the stories more intriguing than the photographs themselves might normally suggest. A series of images (some of which are wider panoramas) documents an unlikely encounter in the Utah desert after the Telluride Film Festival in the summer of 1978, whereby Wenders comes upon a car with flat tire, which turns out to be driven by the director Martin Scorsese and the actress Isabella Rosselini (who were later married for a short time); as Wenders’ captions explain, after Scorsese jacked up the car, he realized there was no spare tire, leading them to join Wenders and his companions in their open-topped car. Other photographs capture Harry Dean Stanton in a limousine with a drink, Bruno Ganz in a hotel lobby, Dennis Hopper in a cowboy hat, John Lurie in a romantic kiss, and Jonas Mekas in a bodega, with Wenders turning the moments into single frame narratives, the anecdotal captions often beginning with “Once, I…”.

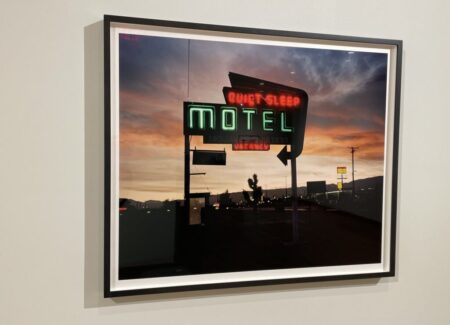

The images from Written in the West are entirely different in form and function. Most obviously, they are crafted in lush saturated color rather than gritty black-and-white, and they feature mostly empty street scenes, storefronts, built structures, and interiors, with no people at all anywhere visible. Wenders made the images while researching locations for Paris, Texas, crisscrossing the American West on road trips through Texas, Arizona, New Mexico, and California. In particular, Wenders was particularly interested by the properties of the intense light in the West; having never made in film in its unique environment, he wanted to use photography to teach himself about how the light interacts with the surrounding landscape, in essence to aesthetically prepare for the kinds of issues he would face in making the film.

Several of the resulting pictures experiment with the falling light of grand Western sunsets, at the moment when the neon buzzes on but there is still twilight in the sky. The combinations are inspired, reminiscent of the saturated colors Joel Meyerowitz tried out a handful of years earlier, with green and red neon sign lettering backed by softened swaths of sky in light orange or simmering red. But when the sun is high and bright in the middle of the day, the visual calculations are altogether different, as seen in Wenders’ efforts to understand how shadows are cast (in the letters of a Safeway supermarket sign) or how white elements and cloudless blue skies interact (in a Cadillac parked in front of an aging drive-in theater and a white trailer set in front of some bold vernacular signage).

Part of what Wenders seems to be trying to photographically grasp is how the built environment sets atmosphere and mood in the West. He tries small town storefronts and movie marquees as subjects, and then gets even more careful with his proportions and compositional spacing in a street scene with a broken Coca-Cola sign and parked cars that are aligned at regular intervals, and a flattened facade in black and white, with rolled down doors, cropped signage, and a faded Coke button arranged with geometric precision. He then notices some moments of potential understated comedy in a scrub desert view with a Western World development sign and in a swimming pool slide seen in the curved notch of a backyard wall, seeming to hit on some of subtle strangeness that sits on the surface in the American West.

For the most part during these road trips, Wenders spent his time outside, gauging the visual constraints and opportunities in the landscape, but during a swing through Gila Bend, Arizona, he stumbled upon a closed hotel that caught his eye. From the outside, he could see an unexpected arrangement of colored leather wingback chairs, and after some local sleuthing, he was able to find someone who would open the place up for him, leading to several interior images that feel trapped in time. The chairs sit in a circle around a hooked rug, seemingly arranged to look at a landscape painting on the wall, or to listen to the old time radio on the sideboard. Another image documents the color echoes of a red leather sofa and a red Coke machine, those reds then leading to an even deeper study of red tonalities in a restaurant image (from a different location in Arizona) with red booths, red light fixtures, and an eerie pattern of decorative symbols on the wall. These images clearly gave Wenders some ideas about the extremes of color he might employ in different settings, which then later appear in the saturated palette he ultimately used so effectively in Paris, Texas.

Seen together, these two bodies of photographic work offer hints of Wenders’ understated storytelling prowess and his scene-setting point of view. His photographs will likely always be a footnote to his larger and more influential film catalog as a director, but the strongest of these compositions provide intermittent evidence of the kind of meticulous visual problem solving that gives his films their unique feel.

Collector’s POV: The prints in this show are priced at $3200, $3500, $4500, $5500, $6500, $6800, $8000, $11500, $12500 (for the diptych), and $15000, based on size, process, and rarity. Wenders’ photographic work has only been intermittently available in the secondary markets in the past decade, with prices ranging from roughly $2000 to $40000.