JTF (just the facts): A total of 28 black and white works, framed in white and matted, and hung against white walls on the five walls of the irregular gallery space. All of the works are electro-carbon prints, made between 1969 and 1975. Each print is sixed 11 x 8 ½ inches and is unique. (Installation shots below.)

Comments/Context: In art, as in life, timing can be everything. William Larson’s collages, done with the electronic aid of teleprinters, were out of step with the photographic majority when he made them between 1969-75. Now, they arrive for exhibition in New York as many younger artists involved with photography are bored by realism and once again in the throes of an obsession with process and non-traditional image making.

Much of the excitement now, as when Larson did this body of work, was about the possibilities of computer graphics. Even if the tools at his disposal were like stone axes and clovis points compared to the digital toolbox available to any 10 year-old today, his reasons for bucking convention are in synch with the poetic impurities of a Lucas Blalock or Letha Wilson.

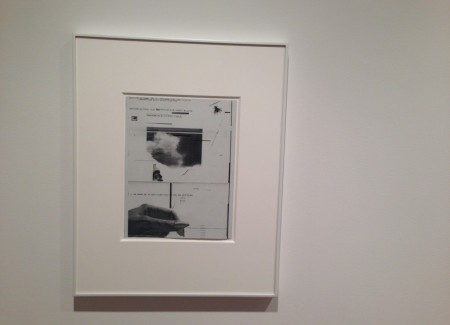

Larson produced his collages—most of them an airy mixture of small photographic images with snippets of text and geometric squiggles—via a pair of Graphic Sciences DEX 1 Teleprinters: one serving as sender, the other as receiver.

A precursor of the digital computer, the teleprinter was invented, Larson has written in a 1985 catalog, “to process all types of data” and to transmit “that data by telephone anywhere in the world.” Based on the principle that images can be converted into sound (and vice versa) the machines allowed him to manipulate the final product by layering what he fed into the teleprinter with typed code, additional images, or with “voice, music or any random audio input into the system.”

The teleprinter scans the photograph (or other visual material) and assigns different voltage levels based on the densities in the gray scale of the originals it reads. “The information is integrated electronically as it transmitted to the receiving machine where the separate parts accumulate sequentially on a special Graphic Sciences paper. This paper consists of three layers: a backing, a layer of carbon, and a fine white paper surface. As the various voltage levels reach the paper a stylus burns the image, line by line, from the surface to the carbon below until its surface is burned completely black.”

Various qualities of this process intrigued him. First, by turning photographs into electrical energy, he was altering their physical status and enlarging their conceptual scope so that they became “a member of a much larger family of imagery.” Second, “everything the teleprinter scans it renders with equality. It is very logical and democratic.” (Warhol appreciated the photo booth for similar reasons.) Third, visual and audio information were able to merge. “Here, perhaps for the first time, the photograph and sound share the same surface equally as both undergo a transformation of their original qualities in order to achieve compatibility.” (This isn’t exactly correct, as the visual has the upper hand; we can only see, not hear, the audio portion of the mix.) Fourth, the teleprinters had a dual identity. They allowed great flexibility “due primarily to the fact that they perform from electronically based principles” but they also operated by certain fixed scientific rules.

Larson imagined these pieces as “a tapestry of personal visual preferences” governed by “rigid technical guidelines.” Despite being mechanically generated, these prints are like drawings. Because of the distance between scanner and stylus and the “noise” that occurs during transmission, it is “impossible to duplicate any single piece.”

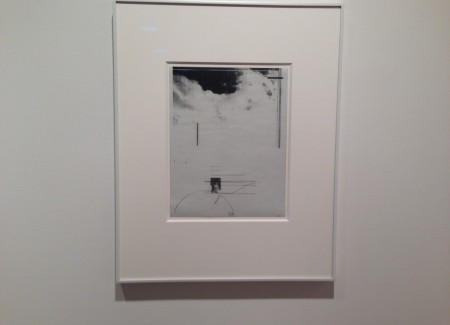

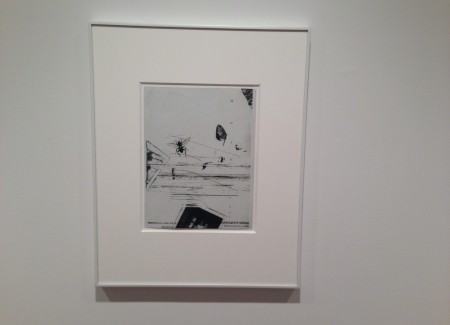

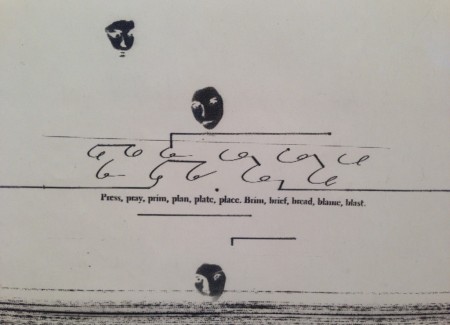

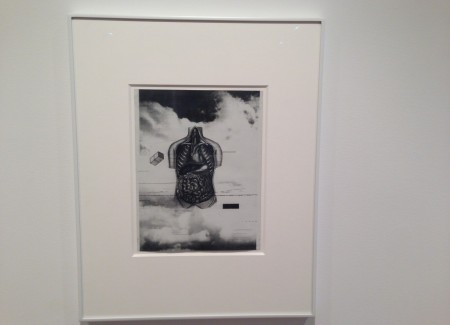

The title of the show, “Fireflies,” refers to the electronic spark behind the making of these images (the burning of the paper with the stylus) and to the the insects that decorate summer evenings. In his choice of images, Larson shows a predilection for lots of clouds, floating body parts (hands, fingers, heads, torsos, lips) bits of concrete poetry (“Press, pray, prim, plan, plate, place. Brim, brief, bread, blame, blast.”), Euclidean forms (bars and cubes), a section of measuring tape, and plenty of bugs (which look more like houseflies than fireflies.) The needle of the stylus at this scale can draw with surprising delicacy. Look closely and the gray sides of cumulous forms are shaded in tiny lines, like the crosshatching in an etching.

Born in 1942 and educated at the Institute of Design in Chicago, where he earned his Masters while studying with Aaron Siskind and Wynn Bullock, Larson took to heart the teachings of the school’s founding professor of photography, Moholy-Nagy. A pioneer of slit-scan photography, he founded the photography department at Tyler School of Art, Temple University and for 18 years directed the Graduate Photography and Digital Imaging program at Maryland Institute College of Art. His work has been regularly featured in surveys of contemporary photography since the ‘70s.

The imagery of “Fireflies” suggests a mind imbued with Constructivism (El Lissitzky) and Surrealism (Max Ernst and Frederick Sommer) as well as tinged by the Pop graphics of Robert Rauschenberg and Keith Smith and lesser-known pioneers in computer art, such as John Whitney, Katherine Nash, and John C. Mott-Smith. And in their marriage of electronic-generated pictures and sound, Larson’s collages also build upon the experiments of Nam June Paik and David Tudor.

It is notable that Larson has acted as curator for a show of work by video artist and former MIT electric engineer Jim Campbell. In the cases of both, technical facility has tended to harm their reputations as dramatic image makers. How their art is done can seem more interesting than the results—even to them.

As Larson’s last one-person show in New York was at Light Gallery in 1981, he is long overdue for another bite of the Big Apple. These modestly sized but boldly imagined works are ancestral to several strains in contemporary practice and would seem to make him a direct ancestor (albeit at 1/100th scale) of the art world’s emerging superstar, Wade Guyton. Here’s hoping that curators and collectors will give him some love.

Collector’s POV: All the prints in this show are priced at $10000. William Larson’s work has very little secondary market history in the past decade. As such, gallery retail is likely the best/only option for those collectors interested in following up.