JTF (just the facts): A large group exhibition of 55 artists, installed on four floors of the museum. (Since no photography is allowed in the galleries at the Whitney, there are unfortunately no installation shots for this show.)

JTF (just the facts): A large group exhibition of 55 artists, installed on four floors of the museum. (Since no photography is allowed in the galleries at the Whitney, there are unfortunately no installation shots for this show.)

The following 10 artists/photographers have photo-based work in the exhibition. Details for each are below:

- Nina Berman: 18 pigment prints, each 10×15, made between 2006 and 2008

- Josh Brand: 5 chromogenic prints and 1 gelatin silver print, either 8×10 or 11×14 or reverse, made between 2007 and 2009

- James Casebere: 2 digital chromogenic prints, each 72×96, in editions of 5, made in 2009

- Babette Mangolte: 441 vintage photographs, 2 decks of vintage photo playing cards, and 1 video, as one installation, made in 2009

- Curtis Mann: 1 bleached chromogenic print with synthetic varnish, 65×153, made in 2009

- Lorraine O’Grady: 4 pigment print diptychs, each individual print 47×38, in editions of 8, made in 2010

- Emily Roysdon: 2 sets of 3 digital chromogenic prints, one with silkscreening, made in 2010

- Stephanie Sinclair: 9 digital prints, each 17×22, made in 2005

- Ania Soliman: 1 digital montage, variable dimensions, made between 2007 and 2009

- Tam Tran: 6 digital prints, each 24×16, made in 2008

Comments/Context: What more is there to say about this year’s Whitney Biennial that hasn’t already been said? Virtually every major art critic in America has already weighed in on the succinctly titled 2010, and as usual, there has been a healthy mix of both supportive praise and scathing derision, peppered with lists of favorites and highlights. Many have connected the show to the momentum for change and redefinition embodied by the election of Obama, others have centered on the majority of women artists included in the exhibit, and still others have latched on to its pared down, recession-friendly curatorial approach. But none of these esteemed writers has comprehensively looked at the photography in the show and tried to consider about what the inclusion of these specific photographers and their work might mean in the larger context of the medium. So that’s what we’re going to try and do here.

Even if we go along with the PR line that this exhibit is not a survey of contemporary American art, but simply an edited sampler or cross section of the diversity of work produced in the past few years, the show clearly has the ability to set out a straw man, pick out some trends, and frame the conversation about what’s been relevant and/or important in the past two years. As such, 2010 should have some compelling things to tell us about the state of contemporary photography, and indeed, this year’s exhibit contains quite a bit of photography in various forms. Since this is not an inclusive biennial of photography, but rather a biennial of contemporary art which includes photography only on its merits, we should be able to see some patterns in where photography is being placed in the larger narrative of new art, or at least analyze how the show’s curators seem to be judging and categorizing what they have found to be new in photography. This does not of course lead to any sort of ultimate truth, but simply a snapshot of how one set of curators has tackled the problem of making sense of it all; so while there are an infinite variety of other ways to approach this same problem, I think a close look at how they seem to have structured their choices can tell us something about how the larger art world is seeing contemporary photography.

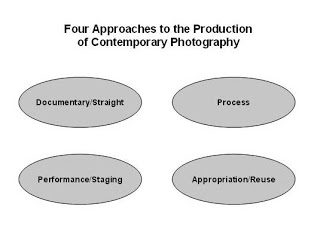

While it seems unlikely that the curators deliberately built a taxonomy of photographic approaches and placed various contemporary photographers in specific locations (they are not photo-specialists after all), the artists who were included in the show can quite easily be placed into one of four “buckets” based on their use of the medium (with a little cross pollination in some cases). I’ve provided a diagram below to make my line of thinking a bit more clear; I’ll cover each group in more detail below.

The 2010 representatives of the documentary/straight approach to photography pack such an emotional wallop that they seem to be saying: make the content extreme or just go home. Stephanie Sinclair’s desperate images of Afghan women charred by self-inflicted burns are bloody and horrifying, so much so that the exhibition room was filled with gasps, “My God”s, and uncomfortable intakes of breath; the suffering and violence that is depicted is harsh and shocking, but entirely unforgettable. Nina Berman’s images of the hometown life of a disfigured soldier (including his thoroughly alienated wedding day) are similarly tragic. Both bodies of work depict the realities of war, and explore the downstream personal effects of our current day social/political choices. As the only two examples of “traditional” photography in the whole show, I was reminded of Paul Graham’s recent comments about the state of medium (here), and the ensuing discussion of the value of capturing unique moments with a camera. If these two photographers are any indication, the contemporary art world isn’t looking for subtlety in its straight photography, it’s looking for outright reaction-provoking challenge.

The 2010 representatives of the documentary/straight approach to photography pack such an emotional wallop that they seem to be saying: make the content extreme or just go home. Stephanie Sinclair’s desperate images of Afghan women charred by self-inflicted burns are bloody and horrifying, so much so that the exhibition room was filled with gasps, “My God”s, and uncomfortable intakes of breath; the suffering and violence that is depicted is harsh and shocking, but entirely unforgettable. Nina Berman’s images of the hometown life of a disfigured soldier (including his thoroughly alienated wedding day) are similarly tragic. Both bodies of work depict the realities of war, and explore the downstream personal effects of our current day social/political choices. As the only two examples of “traditional” photography in the whole show, I was reminded of Paul Graham’s recent comments about the state of medium (here), and the ensuing discussion of the value of capturing unique moments with a camera. If these two photographers are any indication, the contemporary art world isn’t looking for subtlety in its straight photography, it’s looking for outright reaction-provoking challenge.

Four photographers included in the show fit loosely into the performance/staging category, although each is using photography in different ways to document or enable their ideas. James Casebere has made a career out of photographing tabletop constructions, and his two images here satirize a fabricated community of pastel colored houses; his timing couldn’t be better, in terms of being a biting look at the ridiculousness of the housing bubble. Tam Tran’s images depict the performances and imagination of childhood; dressed in Spiderman pajamas and a cape, her nephew uses a long stick to fight invisible evildoers, well aware of the presence of the camera. Emily Roysdon’s photographs are documents of public locations to be used in future performances. An array of chairs (alternately covered with dots and silkscreened dancers) and wood pilings of abandoned piers in the water are both spaces/stages that have been and will be transformed by theatrical action; the sense of being part of the audience is palpable. And Babette Mangolte’s installation of 1970s/1980s photographs and video is less about any specific picture and more about the process of perception and interaction with imagery; composites, variations and patterns of images are seen on a huge gridded wall, while a video overlays sounds from the flipping and shuffling of cards and the tearing of paper. The entire environment is a reflective performance about the how we experience photographs.

While neither Lorraine O’Grady nor Ania Soliman might usually be considered a “photographer”, both are using the recontextualization of appropriated photographic imagery as the basis for the art included in this show. O’Grady’s works juxtapose found images of Charles Baudelaire and Michael Jackson in varying color tones, wryly commenting on the ups and downs of celebrity. Soliman layers a wide range of found images of pineapples into a photomontage alphabet stuck directly to the wall, merging text and photographs into a hybrid historical survey reminiscent of Dada collages. With these examples, it is clear that we have moved beyond the irony of simple appropriation/mashup and on to more complicated and conceptual combinations of images with social/political overtones.

The last group of artists is thoroughly embedded in the technical processes of photography, reveling in the details of the darkroom, the chemical properties of prints, and the object quality of end product photographs. Curtis Mann’s grid of photographs begins with appropriated images from the 2006 war between Israel and Hezbollah (and so ties him to the appropriation group described above). But Mann is more interested in the photographs as objects than in composing pictures from behind the camera: he has subsequently used bleach and varnish to selectively manipulate/destroy the original images, leaving whitewashed expanses of nothingness populated by glimpses of small details, like a cloud of dust obscuring our vision. Josh Brand has opted for making camera-less images in the darkroom, creating abstract photograms of the details of his everyday life.

In terms of sheer “memorableness“, I found the work of Sinclair, Berman, Casebere, and Mann to be the most compelling and likely to lead somewhere exciting or new. Many of the others seem to be working in styles that we have seen before (in the inbred world of photography), but have yet to coalesce into wholly original lines of thinking. Taking a straight photograph, documenting a performance, appropriating an image, or mastering a process are not enough to make it in the 21st century art world; there are some forgettable photographs here I’m afraid. The photographic works I found most thought-provoking in this show were those that are built on layers of outward looking ideas and realities, that took on the larger forces in our society at this particular moment in time, rather than those that were overly self-conscious or inwardly reflective. The disruptions I saw were based in the context of the times, rather than the fabric of ourselves.

If I take the Whitney Biennial 2010 at face value, it is the straight photographers who are out on the bleeding edge of photographic art, pushing our collective consciousness, and the others who have heretofore considered themselves to be cleverly innovative and conceptually original that are being found to be lagging behind a bit. That’s a wholly unexpected and surprisingly refreshing photographic conclusion, and the single best reason to go and see this show.

Collector’s POV: Discovering which galleries represent the artists and photographers in this show isn’t terribly easy. I’ve listed below those that I have been able to find; I’m hoping diligent commenters can point us all toward the rest.

- Nina Berman: Jen Bekman (here)

- Josh Brand: Herald St. (here)

- James Casebere: Sean Kelly Gallery (here)

- Babette Mangolte: Broadway 1602 (here)

- Curtis Mann: Kavi Gupta Gallery (here)

- Lorraine O’Grady: Alexander Gray Associates (here)

- Emily Roysdon, Stephanie Sinclair, Ania Soliman, Tam Tran: unknown

Rating: * (one star) GOOD (rating system described here)

- Reviews: New York Times (here), New York (here), Village Voice (here), Washington Post (here)

- Feature/Curator Interview: Interview (here)

- Nina Berman artist site (here)

- Josh Brand artist site (unknown)

- James Casebere artist site (here)

- Babette Mangolte artist site (here)

- Curtis Mann artist site (here)

- Lorraine O’Grady artist site (here)

- Emily Roysdon artist site (here)

- Stephanie Sinclair artist site (here)

- Ania Soliman artist site (unknown)

- Tam Tran artist site (here)

Whitney Biennial 2010

Through May 30th

Whitney Museum of American Art

945 Madison Avenue

New York, NY 10021

This is a great review. Very direct, very strong.

The photographic works I found most thought-provoking in this show were those that are built on layers of outward looking ideas and realities, that took on the larger forces in our society at this particular moment in time, rather than those that were overly self-conscious or inwardly reflective. The disruptions I saw were based in the context of the times, rather than the fabric of ourselves.

I'm totally with you on this, but I wonder how many leopards will be able to change their spots?