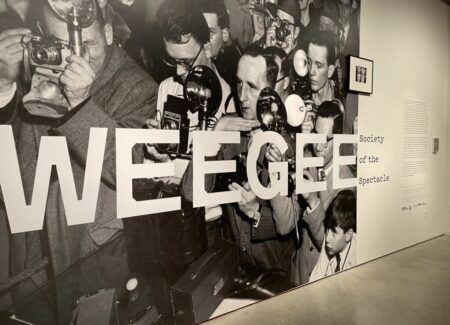

JTF (just the facts): A retrospective exhibition, including over 100 photographs and other ephemera, hung in a series of rooms on the second floor of the museum. The exhibit was curated by Clément Chéroux. Earlier iterations of the exhibit were held at the Fondation Henri Cartier-Bresson and the Fundacion MAPFRE in 2024.

The following works are included in the show:

Entry

- 1 gelatin silver print, 1941

- 1 book, 1987

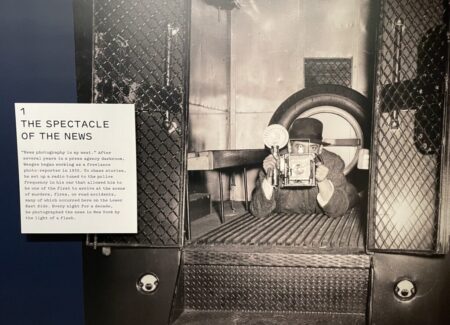

The Spectacle of the News (against blue walls)

- “Weegee in the Flesh”: 6 gelatin silver prints, c1938, c1939, 1941, c1943, c1944, 1950

- “Murder is My Business”: 4 gelatin silver prints, 1936, 1942, c1942

- “Car Wrecks”: 6 gelatin silver prints, c1940, 1941, c1941, 1942, c1950/1994

- “The Tragedy of Fire”: 3 gelatin silver prints, 1942, 1943, c1947

- “Social Documents”: 5 gelatin silver prints, c1940, 1941, 1943, 1944, c1944

- “Red-Faced and Red-Handed”: 5 gelatin silver prints, 1937, c1938, 1942, 1945; 1 magazine cover, 1940

- “Caught in the Act:”: 6 gelatin silver prints, c1938, c1939, 1942, 1943, 1944

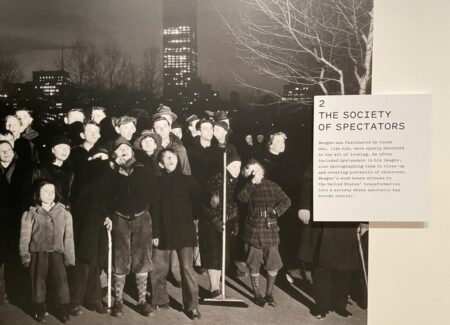

The Society of Spectators (against white walls)

- “The Onlookers”: 3 gelatin silver prints, 1939, 1941, c1944; 1 newspaper, 1941

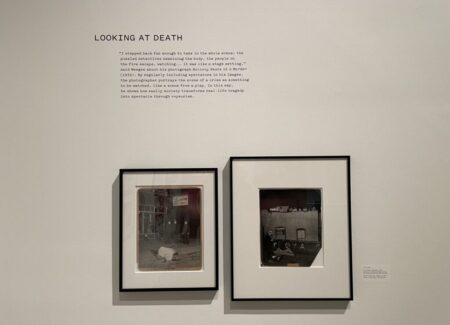

- “Looking at Death”: 3 gelatin silver prints, 1939, 1941

- “The Critic”: 2 gelatin silver prints, 1943

- “Meta Photo Co.”: 4 gelatin silver prints, 1939, 1941, 1942; 1 newspaper, 1942

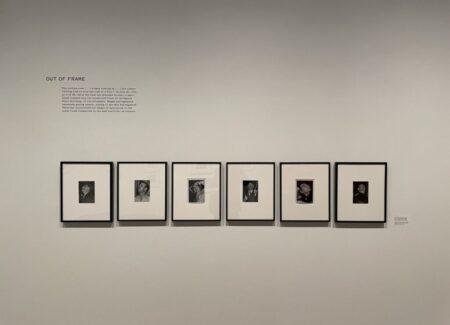

- “Out of Frame”: 6 gelatin silver prints, 1943, 1945

- “Seeing in the Dark”: 8 gelatin silver prints, 1943, c1943, c1945, c1955

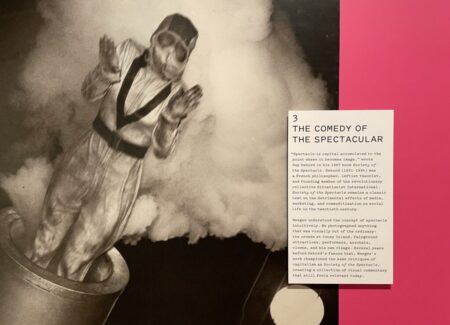

The Comedy of the Spectacular (against pink walls)

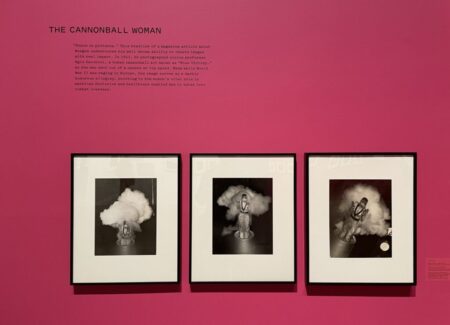

- “The Cannonball Woman”: 3 gelatin silver prints, 1943

- “A Community of Performers”: 5 gelatin silver prints, 1943, c1943, 1944; 1 newspaper, 1943

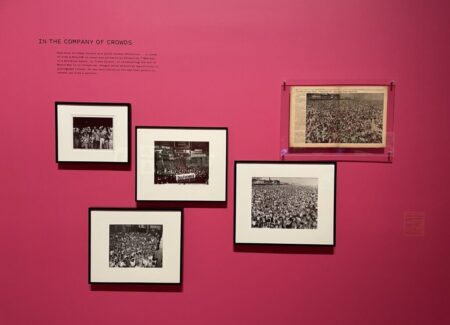

- “In the Company of Crowds”: 4 gelatin silver prints, 1940, 1942, 1945, 1951; 1 newspaper, 1940

- “Gestures of Art”: 3 gelatin silver prints, c1946

- “Photo-Caricatures”: 12 gelatin silver prints, c1958, 1959, c1962, 1963, c1963, c1965, c1966

- (portraits of Weegee): 5 gelatin silver prints, c1960

- “A Box of Tricks”: 3 films, 1952-1965, 1955, 1955-1959; 1 book, 1964; 17 magazine spreads, 1951, 1953, 1955, 1956, 1958, 1960, 1962, 1963

- “A Longer Look”: 3 gelatin silver prints, c1963

- “Weegee/Ouija”: 5 gelatin silver prints, c1958, c1963

(Installation shots below.)

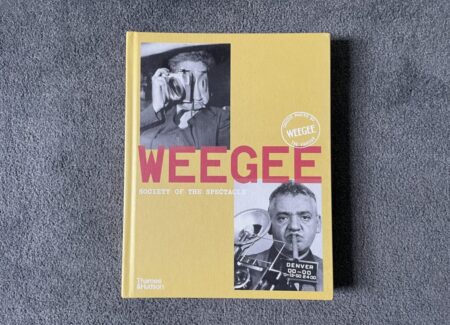

A catalog has been co-published by Thames & Hudson (here), the ICP (here), and the FHCB to coincide with the exhibition. Hardcover, 8.2 x 10.4 inches, 208 pages, with 130 black-and-white reproductions. Includes essays by Clément Chéroux, Cynthia Young, Isabelle Bonnet, and David Campany. (Cover shot below.)

Comments/Context: Curators of full career artistic retrospectives almost always have to deal with the thorny problem of how to handle the lesser known and more under appreciated works. The path of least resistance is to liberally edit them out, guiding the survey to the simpler story found in the most iconic images. But a richer and often more insightful approach is to tackle the messy (and sometimes distracting) artistic detours head on, thereby tying even the most obscure or disliked works into the larger arc of artistic development being communicated.

In the case of the photographer known as Weegee (aka Arthur Fellig), the familiar thumbnail summary of his career revolves around his time as a 1940s era New York tabloid photographer. It’s a brashly sensational story, one filled with police scanners, paddy wagons, perp walks, and flash lit dead bodies on the sidewalk seen from close proximity, and it’s essentially the one told in the 2012 exhibit of his work titled Weegee: Murder is My Business (reviewed here). And while this new retrospective travels to many of those same gritty locations, it has a different agenda. It seeks to make sense of the drastic break in Weegee’s career that took place in 1948, when he left New York behind and moved to Hollywood. His work from this second part of his career has long been dismissed and disparaged (MoMA curator John Szarkowski deemed much of it “deeply vulgar”), but curator Clément Chéroux takes on the challenge of reconciling these later works with Weegee’s earlier interests and aesthetics. Weegee: Society of the Spectacle is the result of that effort, successfully repackaging the previously two-halved Weegee story into a coherent whole.

The first section of the exhibit delivers the Weegee we expect, the down and dirty tabloid Weegee chomping on a cigar and hanging around urban crime scenes looking for a shocking picture he could sell. The edit here is masterful, in that it really highlights just how tremendously strong Weegee was in terms of crafting a composition. Again and again, he makes the mundane details of the aftermath of a crime come alive, almost regardless of whether the incident in question was a gun fight, a murder, a car wreck, or a building fire. He notices a loose gun, an overturned hat, a chalk outline, a pool of blood, a draped body, a smashed face, a single shoe, a crumpled car being pulled from the river, or an ironic juxtaposition of nearby signage and turns those observed details into bold pictures that tell the story with dramatic energy and swaggering style. Weegee had particular fun with moments at the police station, where gangsters and criminals come out of the paddy wagon and are forced to walk in front of the blinding gauntlet of reporters and photographers; he made countless images of people covering their faces (with hats, handbags, newspapers, and the like), as well as pictures of figures emerging from police vans or seen through mesh grating, his blasts of flash amplifying the feeling of sensational performance.

As consistently excellent as these photographs are, the second part of the exhibition makes the argument that Weegee’s essential contribution to the history of photography wasn’t so much his obvious talent as a tabloid photographer, but it was his idea to turn his camera toward the spectators gathered around at the crime scenes he was visiting. His insight was understanding that their expressions, behaviors, and reactions to death and depravity could be just as compelling and emotionally engaging as anything visible in the actual aftermath of a crime or disaster, and it is his raw images of crowds, onlookers, bystanders, and individuals hanging around these events that look more and more powerful with the passing of time; in a sense, what Weegee did best was transform everyday news into voyeuristic spectacle. His photographs document a parade of human emotion – of course, he captures anguish and tears, but also disbelief, rage, horror, curiosity, excitement, astonishment, and even glee. Weegee seems to have quickly internalized this concept of performative watching, and then expanded on it in his famous image “The Critic” (which is essentially a staged reaction shot), cropped images of faces looking up, images of moviegoers in darkened theaters, images that included other photographers in the foreground, and wide views of astonishingly dense throngs at Coney Island and in Times Square. His genius is rooted in moving from a distanced and passive witness to an active participant, noticing the act and context of seeing taking place not just the news.

The jolt in Weegee’s career comes in the spring of 1948, when he leaves New York and moves to California. After more than a decade in the bustling streets of New York city, it’s not impossible to believe that he was simply worn out by the daily grind of tabloid journalism and decided to retire from the game. It certainly didn’t help that the Photo League (a group he had increasingly been a part of) had been blacklisted and that his main newspaper PM Daily had recently closed its doors. What Chéroux teases out is that Weegee’s move to Hollywood makes complete sense if we’re charting Weegee’s interest in the artistic complexities of visual spectacle – once you’ve mastered the eccentric parade of New York, the only place more extravagant to go (at the time) was Hollywood, which is where he went.

The last section of this exhibit takes a closer look at Weegee’s final artistic chapter, the one that has consistently flummoxed critics and curators alike. Chéroux begins his rehabilitation project by making the transitional argument that Weegee essentially traded the spectacle of New York death, murder, and crime for the spectacle of Hollywood glamour, particularly as seen in movie openings, premieres, entertainers, and celebrities of all kinds. But just as Weegee had cast a critical eye on the ravenous voyeurism of New York crowds, Weegeee applied a similar incisiveness to the grotesqueries he saw in Hollywood. His images of a cannonball woman being ejected into the air and of the mannered theatricality of clowns and other performers, both made earlier in New York, seem to set the stage for the playfully biting aesthetic approach Weegee brought to Hollywood.

No recounting of the Weegee story would be complete without mention of his acknowledged position as a relentless self-promoter, and he readily applied the hustling renown he had developed on the streets of New York to digging up commissions for celebrity portraits, film shoots, and magazine features when he arrived in California. But at this point in his artistic career, Weegee’s eye for grand human spectacle wasn’t satisfied with what he could document around him, and he seems to have acutely felt the performative ridiculousness of the celebrity culture he was being asked to promote with his pictures. Earlier in his career, Weegee had clearly been aware of the realties of class divisions, power imbalances, and political clout, and had made many photographs that had overtly exposed those frictions. By the time he got to Hollywood, it seems his patience with these forces had largely run dry, which perhaps led him to the exaggerations and amplifications of photo-caricature as a way to tease (and belittle) those who had gotten a little too big for their britches.

In a different artistic context, perhaps as applied to less famous subject matter, the many distortion techniques Weegee used to make his photo-caricatures might have been seen as surreal, or avant-garde, or even innovative. His “elastic lens” (as he called it) included a dizzying array of interventions, both in front of the lens (mirrors, prisms, plastic sheets, textured glass, and kaleidoscopes) and behind it (manipulated films, montage, and multiple exposures). But when he applied these approaches to the likes of Jackie Kennedy, Elizabeth Taylor, Marilyn Monroe, Ronald Reagan, Charlie Chaplin, Mao Tse Tung, and other very public figures (with exaggerated puckers and smeared smiles making fools of them all), his photographic satire was characterized as gimmicky trickery rather than technical revolution (although his pictures did indeed sell magazines.) It seems one of the few artistic figures who didn’t ignore Weegee’s ideas during this period was the film director Stanley Kubrick, who knew Weegee from his New York days and hired him to make spontaneous images on the set of Dr. Strangelove (as an aside, apparently the goofball European accent that Peter Sellers adopted for Dr. Strangelove was a parody of Weegee’s own voice). Weegee ultimately made a series of images of a cream pie fight in the war room (a scene which was cut from the final film) and some circular portraits that looked like they had been taken looking through the wrong end of a telescope.

What I appreciate about the way Chéroux has approached Weegee’s career is that he hasn’t taken the received wisdom for granted. His structuring amply reinforces the durable strength of Weegee’s tabloid work, while essentially rejecting the polarized before/after construct of Weegee’s New York/Hollywood life. Instead he plausibly argues for more of a continuum, where the late work isn’t entirely flippant visual junk made by a past-his-prime photographic grifter, but instead the logical end point of a photographic life increasingly interested in flashy surfaces and spectacle. Certainly, some of Weegee’s most crass distortions are little more than visual one liners, but others offer more technical complexity than a simple warp or twist, and their scathing critique of 20th century pop culture (particularly in the straight laced 1950s) deserves to be judged with more than a dismissive glance. Chéroux’s thoughtful show has convinced me that Weegee’s late distortions aren’t an outlier or an aberration, but the place where a career-long progression of artistic ideas culminates in something wildly unexpected.

Collector’s POV: This is a museum show, so of course, there are no posted prices. Since Weegee was so prolific, dozens of his photographs are routinely available at auction in any given year. Recent secondary market prices have ranged between roughly $1000 and $63000, with the vast majority available for under $5000.