JTF (just the facts): A total of 15 large scale color photographs, framed in black and unmatted, and hung against alternating red and white walls in the entry area, the main gallery space, and two smaller back rooms. All of the works are digital c-prints, made in 2011 or 2014. Physical dimensions range from roughly 71×88 to 71×119 (or reverse), and the prints are available in editions of 6. There are 3 prints in the entry gallery, 7 in the main gallery, 2 in back gallery A, and 3 in back gallery B. (Installation shots below.)

Comments/Context: It was inevitable that after making photographs from thread, perforations in paper, sugar, Bosco, flowers, and dirt, Muniz should get around to making photographs out of photographs. All of the enormous prints here (many larger than 8 ft. by 5 ft.) are mosaics constructed of paper. Based on photographs of small dimensions, which Muniz has collected over many years, and then built by hand out of even smaller ones, they can be read at various distances. From afar, they cohere into identifiable pictures of a person or place, usually with temporal referents that mark the scene with a date of origin.

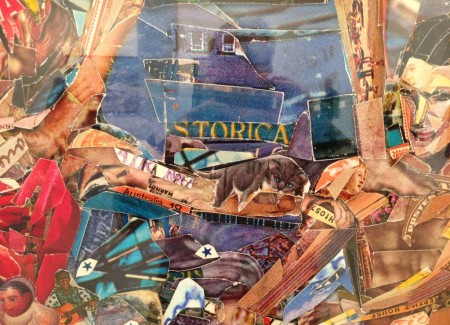

It is only upon moving closer that the integral wholeness and solidity of the picture plane dissolves and is revealed to be an illusion. We are, in fact, looking at a messy scrap heap: the remains from hundreds of photos and postcards after shredding. Although none of these pieces are complete photographs themselves, many slivers contain traces of their owners in the shape of handwriting or are marked by their country of origin in the form of postmarks or stamps. A face or a seascape or a jetliner is not a smooth, continuous surface but an irregular one, tweezered together from clumps of recycled paper and modeled into these terraced forms that have been rephotographed into flat c-prints.

In the last few years Muniz has been applying this treatment to two groups of pictures. The more numerous in this installation are sepia-tinted and loosely follow the progress of what might be called a “typical” life in the late 20th century. After the title of each image he has added the word “Album” to suggest an interconnectedness between these mementoes.

The first room includes a courtship snapshot of a couple in a rowboat; a formal portrait of a bride and groom at a wedding; and a close-up of a child’s bonneted face. In the second room is a family portrait of parents, siblings, and relatives gathered around a cake on a table for a one-year old’s birthday party. There is also a co-ed portrait of elementary school children seated in a classroom; a young man proudly posing beside his new ‘40s-era automobile; and a pair of images that could be vacation relics: a couple posing in front of Rodin’s “Thinker”; and a barelegged woman in sunglasses reclining in a chair on an apartment balcony.

Along with this group are four pictures that bear the subtitle “Postcards from Nowhere.” More brightly colored (turquoise skies or water) than those from a photo album, they are even more generic: a sweep of beach from far away and high above; a pyramid of water skiiers; a jetliner on a runway; a panorama of the lower Manhattan skyline seen from the Hudson River.

Muniz is never less than clever and this body of work is no exception. In the substance and process of their creation, these pictures illustrate how photographs can be highly specific (a precise record of existence in time and space) as well as thoroughly generic. A family snapshot is a conceptual mash-up, documenting experiences recognizable by millions of us who were never there and not too different from (or more private than) a tourist souvenir. Both types of images have proven to be effective in transmitting memories to strangers across continents and decades.

Social critiques of photography have continually, if quietly, infiltrated Muniz’s oeuvre. Postcards can mask the violent realities of history: the beach here depicts Beirut, the jetliner is operated by Somali airlines, the New York skyline has the World Trade Towers standing tall. Black people appear only twice in the snapshots: in a beige-tinged portrait of a military band member, and in the children’s classroom where a single dark face can be seen in a sea of white boys and girls. Otherwise people with this skin shade weren’t pasted into the Family of Man’s album.

The series further suggests that Muniz doesn’t belong to any school. His decision not to search in the world with his camera for new images but to base his art on preexisting ones allies him with Picture Generation artists, such as Richard Prince and Sherrie Levine, both of whom have expressed a weary disgust at the number of photographs that already exist. They haven’t seen the need to add to the garbage pile.

At the same time, there is a boy scientist side to Muniz that isn’t smartass or ironic. His deconstructions of photographic realism are more playful but just as curious about the eye’s need to find patterns out of random points of darkness and light, as Chuck Close’s work has been for the last 40 years.

Muniz doesn’t want to banish the hand from photography. If in his previous series he has acted as a painter, weaving lines and voids out of assorted untraditional materials, he is acting here as a sculptor, molding curves and shadows out of scissored photographic paper without falling back on computer assistance. His composting of images extends the reclamation work he has been doing in the Brazilian favelas, documented in last year’s film Waste Land.

Walking through the show, however, I found myself respecting his diligence but unmoved by the ultimate results. By exploding old snapshots and postcards in order to reuse them as building material for new, big, pricey art objects, he has robbed the originals (whatever or wherever they may be) of their humble character. It is sobering to consider that those individual aspects of our lives preserved in photographs belong to a generic worldwide ocean of experience. But it’s the worthlessness of such photographs to anyone outside members of our family or beyond the writer/recipient of a postcard that was the source of their emotional strength, and Muniz’s ingenuity has taken it away.

Collector’s POV: The prints in this show are being sold in two-tiers: $45000 for the various sizes on display in the gallery and $32000 for standardized 40×60 (or reverse). Muniz’ works are ubiquitous in the secondary markets for both photography and contemporary art, with dozens of images available at auction every season. Recent prices have continued to rise, ranging between $5000 and $270000, with prints most finding buyers in five figures.