JTF (just the facts): A total of 19 photographic works, installed in the main gallery sapce, the entry area, and a smaller back room. (Installation shots below.)

The following works are included in the show:

- 4 UV prints on glass, mirror, aluminum frame, 2024, sized roughly 65×52, 24×30, 20×17, 52×65 inches, unique

- 10 archival pigment prints, 2024, sized roughly 20×16, 20×24, 24×31, 41×33, 50×41, 64×78, 64×79, 64×80 inches, in editions of 3+2AP

- 1 gelatin silver print, 2024, sized roughly 41×51 inches, in an edition of 3+2AP

- 4 dye sublimation prints on fabric, walnut artist’s frame, 2024, sized roughly 62×44, 65×48, 33×16, 74×48 inches, unique

Comments/Context: Ghosts, apparitions, and memories liberally inhabit Tyler Mitchell’s first gallery show at Gagosian in New York, infusing the photographs with more implied tumults and psychological traumas than we have typically seen in his work to date. This layering takes place both literally and figuratively, with the truths of black history consistently bubbling up to subtly disrupt the dream-like atmosphere that Mitchell has made his signature. In this new show, he’s actively stretching his expressively sensual aesthetics, and testing the limits of how joy and beauty can be freighted with damage.

For those that may not have been tracking the artist closely, Mitchell’s photographic career has been on a rocket-like trajectory over the past handful of years. Many mark the beginning of his ascendancy with his 2018 portrait of Beyoncé for Vogue, making him (at 23) the first black photographer to shoot the cover of the fashion magazine. This was followed in quick succession by inclusion in Antwaun Sargent’s influential “New Black Vanguard” survey in 2019 (reviewed here), a museum solo at the ICP in 2020 (reviewed here), and a New York gallery solo in 2021 (reviewed here). Since then, his momentum has continued to accelerate, culminating in a new representation relationship with Gagosian in 2022, which began with a solo show in London.

What initially set Mitchell apart, and what has continued to make his photographs durably memorable, is his broadly positive visual mindset – he consistently sees the richly engrossing beauty in black people and stages his subjects in moments of child-like play, comfortable relaxation, freedom, and peace that feel almost otherworldly. In many ways, his images boldly cut against deeply ingrained discriminations and stereotypes, and instead offer a re-imagined contemporary reality, where everyday black leisure is celebrated with effortless whimsy, warmth, and ease.

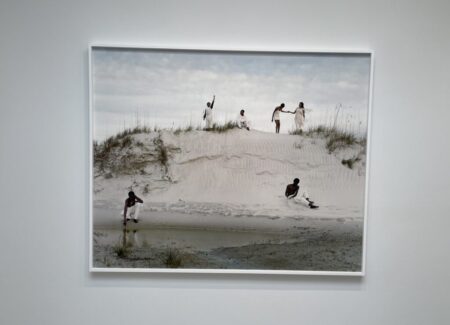

Mitchell’s new works find him back in his home state of Georgia, in particular traveling out to the Jekyll and Cumberland barrier islands on the coast. The setting is naturally filled with dunes, beaches, parks, and seaside attractions, but is also invisibly weighed down by its history as a former landing spot for slave ships and as a plantation site owned by the Carnegie family. This tension fills the resulting photographs, where idyllic surfaces and bucolic staged moments simmer with quiet undercurrents of friction.

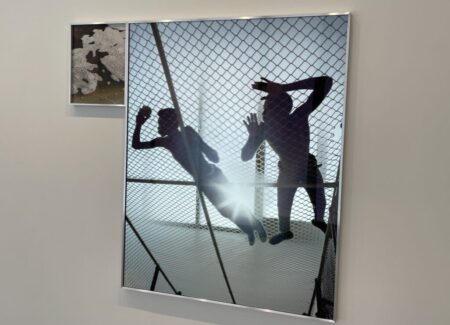

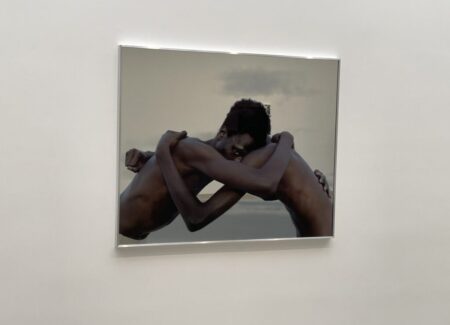

While all of Mitchell’s recent works start with photography, it’s clear he’s been experimenting with a wide range of aesthetic strategies, printing methods, and display approaches to find the right mood for any given picture. Several images have been printed on mirror and framed in shiny aluminum, adding metallic brightness to the compositions. This is particularly effective in the large works “Old Fears and Old Joys” and “An Embrace”, where the dark gestural forms of young bodies are amplified by the surrounding absence, creating a glorious floating effect; it is less useful in the smaller works “Buoyancy” and “Gulfs Between” where the mirror creates pockets of bright sparkle that don’t meaningfully change the images except to enhance their sense of fleeting magic.

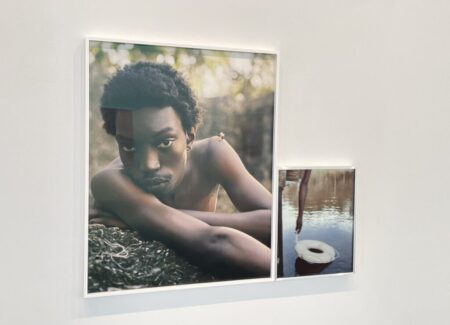

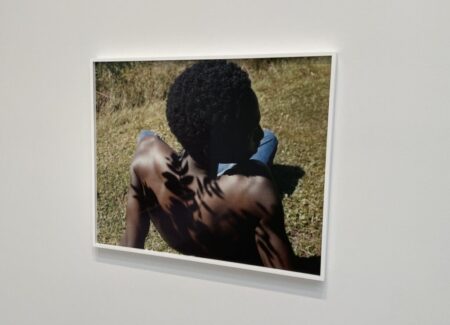

Mitchell has built his fashion career on his talents as a portraitist, and there are a handful of superlative portraits included here that show off that strength. “Simply Fragile II” features a bug perched on a young man’s shoulder, while “Shine” plays with a leafy shadow cast across a young man’s back, both pictures capturing a sense of luxuriating ease and tender gentleness. His image of a young woman in a floral bathing cap is similarly graceful and stylish, using a weathered wooden post to bisect the composition. “Ghost Image” is the most provocative of the portraits, in that it drapes a young man in twisted netting, like a trapped fish; the visual allusion to the legacies of slavery is obvious, his posture fighting the weight of that history.

Another aesthetic approach Mitchell has been refining in the past few years has been his controlled use of multiple figures in a single scene. In his last show, he offered scenes carefully arranged on grassy knolls, hillsides, playing fields, and even in an amphitheater, and the seaside locales in Georgia provide several opportunities for similar compositions of individuals, groups, and families all in one frame. “Rock Skip Tableau” features multiple gestures – standing, sitting, squatting, throwing – all framed by the shadowy slats of the boardwalk. The other two tableaux are more open and beach oriented, and echo some of the mannered 1940s era setups of white garbed figures with driftwood and dunes of PaJaMa.

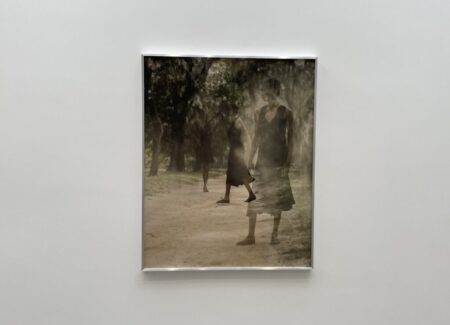

Mitchell leans into the ghost theme more literally in two images that feature multiple exposures. In “Lamine’s Apparition”, Mitchell makes a nod to Frederick Sommer with an elemental black-and-white portrait that seems to float amidst textural wooden planks, and in “Gwendolyn’s Apparition”, he multiples a young woman into three misty figures turning as they stroll down a dirt path. In each case, Mitchell seems to be bringing forth ghosts from the past, who linger in the landscape waiting to be acknowledged and appeased.

The weakest works in this show are Mitchell’s fabric-printed works, which is altogether surprising since Mitchell has made so many compelling fabric photographs in the past, including an entire hallway in his ICP show filled with laundry-like lines of gracefully fluttering imagery. The problem here lies in the wooden frame supports over which the fabric works are draped; they anchor the pieces to the wall in a way that makes them fall limp rather than move with ethereal lightness, with the strict geometry of the rectangles adding to the distraction. The strongest image of this group features a young man holding a kite, where the light of the sun is cast through the kite, and thereby through the fabric; this picture has the potential for layered visual magic, especially given the connection between the braces of the kite and the frame below, but the potential energy never quite coalesces. Other works add to the ghostly refrain with images that drift in and out of legibility, or seem to move in a swirling twists that are echoed by the veiled curves in the fabric. But none of these efforts quite delivers on the liltingly tactile transparency that Mitchell’s previous works on fabric have generally offered.

As more black photographers choose to visually excavate the coastal areas of the American South, it’s intriguing to see how they are each individually adapting their aesthetics to the complex circumstances. For Mitchell, whose eye for warmth, beauty, and tenderness has catapulted him into photographic prominence, grafting darker psychological memories and histories onto his work adds unease to a fundamentally easy vibe. The result is a set of works that have more jangly stress than we’re used to seeing from Mitchell, where tiny waves of emotional tightness noticeably disrupt his usual sense of enveloping calm.

Collector’s POV: The works in this show are priced between $15000 and $50000 each. Mitchell’s work has little secondary market history at this point, so gallery retail remains the best option for those collectors interested in following up.