JTF (just the facts): A total of 81 black and white and 5 color photographs, variously framed and matted, and hung against white walls in the multi-room exhibition space. All of the black and white works are gelatin silver prints (most posthumously printed), made between 1979 and 1987. The color works are c-prints, made between 1983 and 1987. There are also several large works made up of sets of Polaroids/gelatin silver prints – 2 sets of 54, 1 set of 59, and 1 set of 80, made in 1980 and 1981. The exhibit also includes 3 newspaper spreads, a slideshow (207 slides, from the 1980s), and 3 artist books (1975-1976). The exhibit was organized by Amy Brandt, curator at the Chrysler Museum of Art. A catalog of the exhibition has been jointly published by the Grey Art Gallery, the Chrysler Museum of Art, and Lyon Artbooks (here). (Installation and detail shots below.)

Comments/Context: For those artists who have produced a body of work that is, for whatever reason, so recognizable that it becomes nearly synonymous with the artist’s very name, the outcome is inevitably both a blessing and a curse. On one hand, signature images and projects become embedded in our collective cultural consciousness, cementing an artist’s place in the long arc of art history. On the other, in the face of such powerful imagery, we tend to overlook the artist’s other artistic endeavors, to the point of really only paying attention to the already well known work. In the worst cases, we inadvertently trap the artist into the role of the aging rock band, being forced to play the same hits again and again.

Tseng Kwong Chi’s East Meets West series (and to a lesser extent, his related follow-on Expeditionary series) was a career-defining set of pictures. Dressed in a severe grey Mao suit and wearing dark sunglasses, he positioned himself in front of many of the world’s most famous landmarks, turning each into a backdrop for his innovative brand of solitary self-portraiture. Part clichéd tourist shot and part rigidly serious conceptual performance, the images stand out for their contrasts, with Tseng always an obvious out-of-place Chinese dignitary, recasting Mount Rushmore, the Brooklyn Bridge, Niagara Falls, and the former World Trade Center towers as players in his own cross-cultural pantomime. Decades before the ubiquity of the selfie, Tseng was inserting his invented persona into the space of the Hollywood sign, Checkpoint Charlie, and the Eiffel Tower, or placing his tiny figure against the grandeur of the land like a 19th century Romantic painting, hijacking the stereotypical postcard scenes and testing the limits of his stylized outsider identity.

For many, these now iconic photographs are the sum total of Tseng’s legacy (he died in 1990 from AIDS-related complications). But this well-edited first museum retrospective goes a long way toward creating a deeper picture of Tseng’s career, taking roughly a dozen of these favorites and placing them in the context of a wider sample of his work. The result is much more than a Mao suit with a shutter release – we see Tseng’s art as a continuum of consistently engaged performance, mixing in political and social critique with the biting eye of a satirist.

The lesser known gems of this show are what give it its revelatory punch. In Costumes at the Met, Tseng gladhanded and posed with dignitaries at the reception for the Costume Institute’s The Manchu Dragon: Costumes of the Ch’ing Dynasty, 1644-1912 exhibit, inserting his persona in amongst the fashion elite and the philanthropy set. The images have a surreal quality, wandering from the ridiculous to the hilariously uneasy, with Yves Saint Laurent, Jerome Robbins, Paloma Picasso and other celebrities and socialites all being caught in Tseng’s momentary photographic net. What’s fascinating is how he turned the bright lights opening into a piece of controlled performance art, insinuating his Mao suit into places and situations that led to socially uncomfortable frisson.

In his Moral Majority series, Tseng exchanged his Chinese garb for a conservative seersucker suit and somehow enticed various Republicans to pose in front of a badly wrinkled American flag (claiming it would look like the wind blowing). These pictures are like something out of the Daily Show with Jon Stewart, where the subjects pose ever so earnestly, not entirely realizing they are the subject of a daring and belittling reversal. His portraits of the leading political figures of the day, from Jerry Falwell to William F. Buckley Jr., are both self righteously serious and quietly comedic, like a time capsule of sharply aimed mockery.

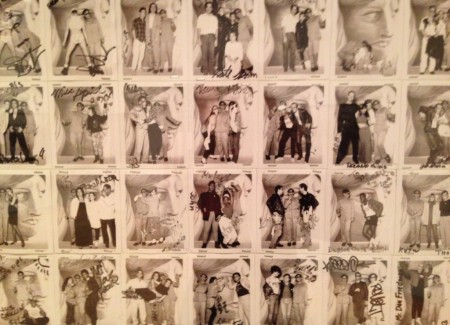

Tseng was clearly most comfortable and at ease in the clubs and art studios of the downtown/gay scene, and his large color portraits of Andy Warhol, Jean-Michel Basquiat, and particularly Keith Haring (and of his many in-process works) are a testament to his position in the underground community. Better yet are his dense montages of nightclub and party portraits (from the Mudd Club and Danceteria to a party commemorating the Princess Diana royal wedding), with Tseng vogueing, mugging, and posing with seemingly every visitor on a given night (often with each image signed by the sitter), his Mao suit often the least crazy of the identities and costumes on display. These grids have a looser, more improvisational quality, and are altogether more fun than many of his more serious set ups; one even uses ink to rubberstamp the “visas” of the revelers, like a passport. In these venues (and in the more staged group portraits of friends on view), Tseng was surrounded by people trying on personalities (he, too, is in drag in a few images), and the acceptingly playful and supportive atmosphere comes through with lively vitality.

Seen together across roughly two decades of work, Tseng’s various masquerades look surprisingly thoughtful and sophisticated. While the East Meets West pictures may always be celebrated as his most refined and influential, this retrospective goes a long way toward seeing Tseng’s art from a broader vantage point, connecting the dots between the stops along a career of innovative performance and fluidly invented persona. It’s the kind of show that will likely help reposition Tseng’s photographs and ultimate contributions with more academic authority, wedging him in not just among his downtown compatriots, but with the wider sweep of penetratingly staged self portraiture across the history of the medium.

Collector’s POV: Since this is a museum show, there are of course no posted prices. Tseng Kwong Chi is represented by Paul Kasmin Gallery in New York (here). Only a handful of Tseng’s prints have come into the secondary markets in recent years, and prices for those lots have ranged between roughly $4000 and $23000.