JTF (just the facts): Published in 2025 by Radius Books (here). Hardcover (9 x 12.5 inches) with fold-out insert, 180 pages, with 90 black-and-white and color images. Includes essays by Lucy R. Lippard, Mark Cheetham, William L. Fox, and Brandee Caoba, and a foreword from Michael Govan. With field notes from the artist and a chronology. (Cover and spread shots below.)

Comments/Context: It’s altogether distressing to think that we might have become somewhat numb to the tragedy documented in images of melting glaciers and ice caps. For the past several decades now, going all the way back to the intrepid explorer photographers of the 19th century, artists and scientists have been avidly documenting the extreme Arctic and Antarctic regions of the globe, as well as the glaciers dotting the planet here and there, all the while visually measuring the ominous truths of the receding ice, the calving faces, and the increasingly rapid melting. At this point, we’ve seen so many glorious photographs of vanished sweeps of ice, sculptural icebergs floating in the sea, and aerial images of crevasses, blue rivers, and other wild formations carved from melt that their collective grandeur (and worrying horror) doesn’t move us as much as they should. Part of the problem lies in the very nature of long time, and our inability to react to slow incremental changes that defy easy visualization; another is rooted in our persistent self-centeredness, and our constant application of a human perspective to the rhythms of the natural world.

Tristan Duke’s photobook Glacial Optics offers an innovative artistic rethinking of the 21st century glacier photography problem, mixing equal measures of science, art, and personal exploratory journey into photographs that take a unique conceptual angle on the larger climate change issue and don’t look like anything we’ve seen before. Duke follows in a long and well-revered line of risk-taking photographer scientists, reaching all the way back to the early inventors of the medium and coming forward to artists like Berenice Abbott, Harold Edgerton, Chris McCaw, and others who have have explored the edges of visual science with cameras (and other hand built apparatus) as their primary tools.

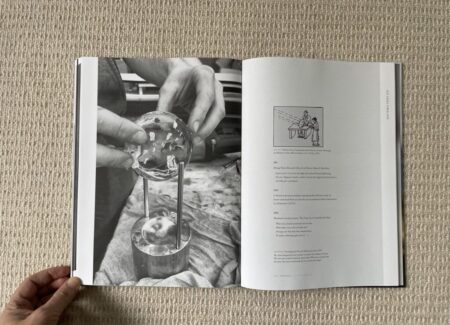

While Duke lives and works in Los Angeles, the story behind Glacial Optics actually begins in New York, at the Strand bookstore of all places. It was there that Duke stumbled upon a reference to a 3rd century Chinese alchemist who used a lens made of ice to start a fire. This tantalizing ice/fire duality led Duke down a rabbit hole of research and investigation, tracking down examples of the use of ice lenses through history and ultimately pushing him to build and refine his own manufacturing process for crafting such lenses, not unlike the one used by Japanese bartenders to melt ice into the perfectly clear round ice balls found in a glass of fancy whiskey. Of course, for a lens to actually work for making a photograph (in a camera obscura setup), it has to have very specific curvature characteristics, which Duke figured out out how to control in his ice experiments.

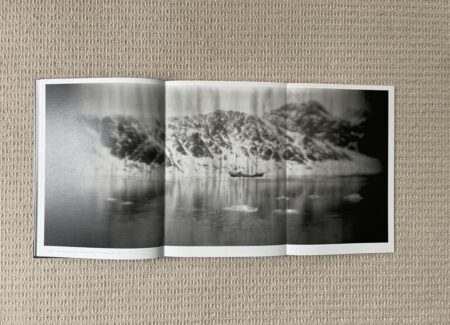

Once Duke could plausibly make and use ice lenses for making photographs, the next logical questions became what ice to use (and where to get it) and what to actually photograph once the ice lens was functional. As it turns out, ice clarity mattered quite a bit to the success of the downstream imagery, and so Duke decided to venture far up north, to the islands of Svalbard in the Barents Sea above mainland Norway, in search of very pure Arctic ice; that location wasn’t a random cold weather choice – it also happens to be the single place on Earth that is warming the fastest due to climate change, making it conceptually a perfect spot to consider the evolving nature of ice. After a journey on a three-masted sailing ship, an outbreak of COVID-19, and various other obstacles and challenges offered by Zodiac trips out in the biting cold, snow, and wind, Duke managed to make a number of exposures using his large scale tent camera and his ice lenses (the negatives were 4×8 feet in size), documenting the surrounding Arctic landscapes, in particular views of the Dahlbreen glacier.

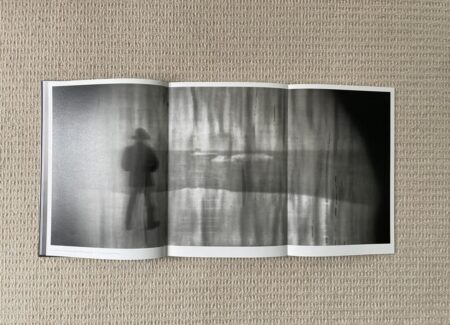

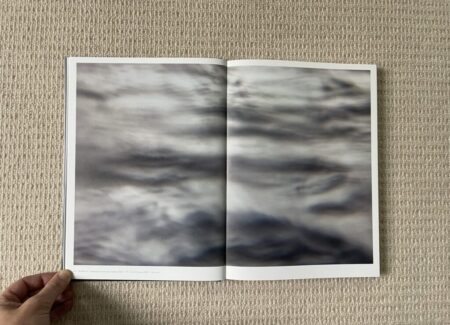

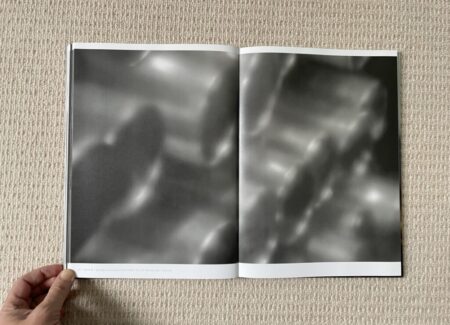

Duke’s ice lens images have blurred, almost pictorial aesthetic, as if they were taken through wavy glass. His black-and-white efforts feel related to other familiar images made by 19th century explorer photographers, with icy bays, moored ships, and standing figures looking out at the desolately beautiful landscapes, with tunneled dark corners and chemical residues adding to the mood of nostalgia. In color, Duke’s views drift further toward enigmatic abstraction, with sparkles and flares of light mixing with clouds, ice, and sea, the forms softened and dissolved by his “glacial ice looking at itself” process. In a few scenes, the ice lens reduces the available detail down to swaths of mysterious color, with one group of red-jacketed boaters drifting off into a soup of enveloping grey.

Conceptually, Duke’s approach relates to that of other artists (like Matthew Brandt) who have incorporated physical aspects of their subjects (like dirt, dust, river water, and tar) into modified photographic processes, thereby literally embedding the land into their photographic landscapes. Duke offers a further twist on that thinking, crafting a lens from the ice that is drawn from location he is photographing, turning the glacier into a “natural optic element” that acts like an eye, in a sense performatively “collaborating” with the ice to create the imagery (perhaps making his pictures a perplexing kind of inanimate self-portrait). The strongest of these glacial ice-enabled works feel altogether elusive and precarious, their blurred fragility reinforcing the deteriorating state of flux they are documenting.

In a second project, Duke re-negotiates the conceptual relationship between ice and subject, aiming his ice lenses not at glaciers but at wildfires, in particular those raging in the American West, from California to Colorado and Montana to New Mexico. In this way, the ice/fire connection is drawn from the same source, with a warming climate not only driving glacial melting, but also the dry conditions and drought that make dense forests a danger zone. Duke’s resulting “ice documenting fire” images apply the soft blurring found in his Arctic views to the charred mountainscapes and smoky blackened hills of the wildfire regions, with a couple of scenes brought down to the intimate level of scorched neighborhoods and houses burned down to their foundations. Several of the color works warp out into twisted distortions and scratchy residues, with fogs and glows matched by calligraphic black branches and erased detail.

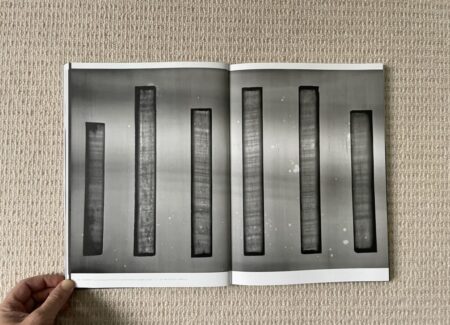

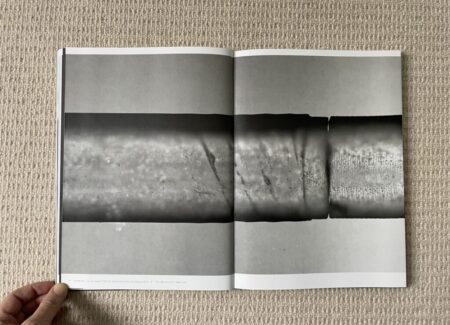

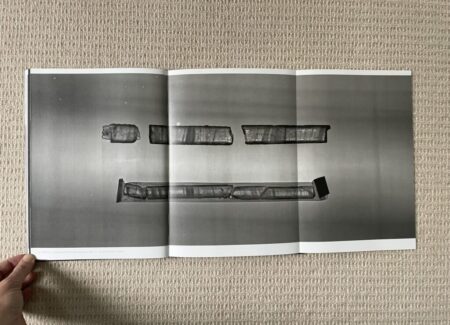

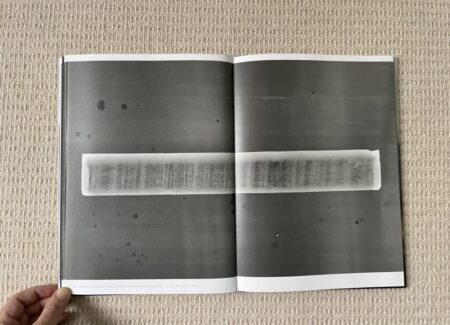

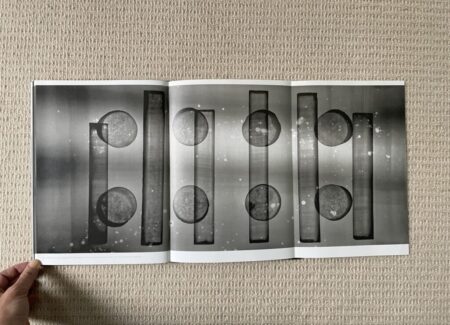

The last section of Glacial Optics changes the conceptual framework once again, now using the ancient ice from discarded ice cores at the National Science Foundation Ice Core Facility (NCF-ICF) to make photograms of various rare core samples. The resulting ice lenses are infused with dust and air bubbles, creating spots that decorate the otherwise straightforward views of the cores. Up close, as illuminated by Duke’s flash, the lines of history reveal themselves, almost like a striated DNA sequence, with the interruptions of different climate events leaving visible marks on the ice cores. Even more than the other two projects, this one is steeped in time, memory, and history, with an ice lens from one point in deep time used to light another.

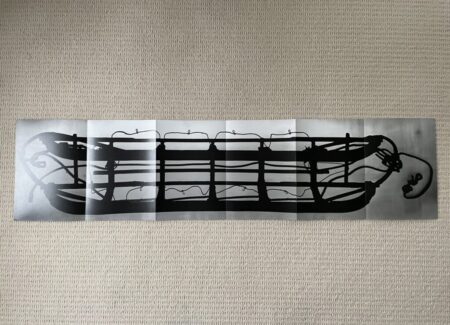

Duke’s Glacial Optics represents a best of both worlds effort, in that it not only has a sophisticated conceptual undercarriage that is filled with rich ideas and technical obstacles that have been overcome, it is populated with resonant images that are visually gripping even if all the details of the backstory are unknown. As a photobook object, Glacial Objects has been painstakingly designed and constructed, with care applied to paper stocks, page sizes, and fold outs, creating discrete sections and logical progressions between images, essays, and supporting notes, the entire package wrapped up in a mood of understated elegance that matches the content well. Even Duke’s massive photogram of a wood and rawhide dog sled used for polar expeditions (originally 18 feet long) has been tucked in at the back, on a folded insert that expands to six panels, almost like an invitation to head off on our own journey of discovery.

Duke’s photographs remind us that rigorous science-heavy thinking and problem solving can still lead to expressively personal aesthetic outcomes. This book belongs on the short list of memorable climate change photobooks of the past decade or two precisely because it tackles the problem from a unique angle, but still delivers imagery that can move us to act. Duke fuses the wonder of invention with the urgency of ecological peril, using the disembodied “gaze of the glacier” to show us a longer view of time.

Collector’s POV: Tristan Duke does not appear to have consistent gallery representation at this time. Interested collectors should likely follow up directly with the artist via his website (linked in the sidebar).