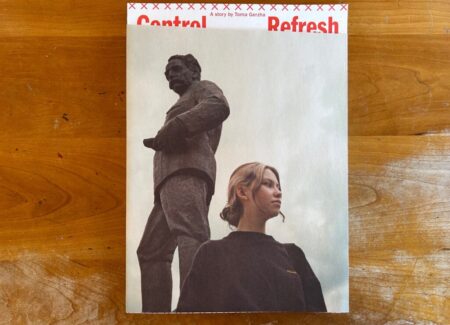

JTF (just the facts): Published in 2024 by The Eriskay Connection (here). Softcover with partial dust jacket and exposed spine, 23 × 32 cm, 160 pages, with 196 photographs. Includes extensive notes and captions by the author. Design by Rob van Hoesel. In an edition of 1200 copies. (Cover and spread shots below.)

Comments/Context: What is it like to be a young adult in today’s world? I’m probably the wrong person to ask. I’m 56 years old, closer to death than adolescence. The yawning disconnect between me and so-called Generation-Z (born roughly 1997-2012) is more of a chasm than a gap. Euphoria, Khaby Lame, sussy baka, sksksk, pushin’ P, cottagecore… every time I have to Google a new meme, it confirms my sense of being out of touch. Note, that’s not a complaint. I accept my status and there’s no use fighting it. But I would like to understand the young folks better. What makes them tick (or Tok)?

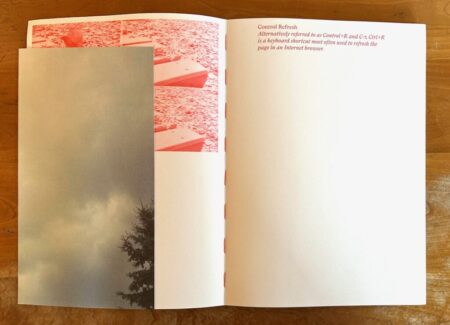

Which brings me to Toma Gerzha’s debut monograph Control Refresh. This is a photobook by a young person (Gerzha is 22), documenting other young people, and addressing the ideals and aspirations of their shared generation. For a Gen Xer like myself, ideally it can function as a Rosetta Stone, a Ctrl-R shortcut to youth to refresh my ideas about them. Perhaps the Paris-Aperture award committee had this potential in mind when it nominated Control Refresh for the 2024 First PhotoBook Award.

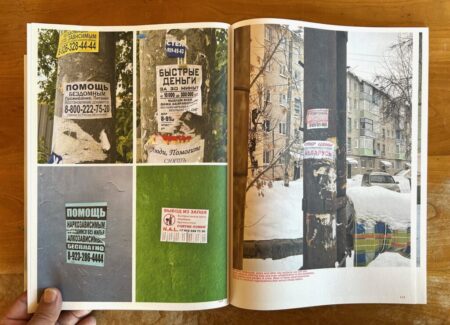

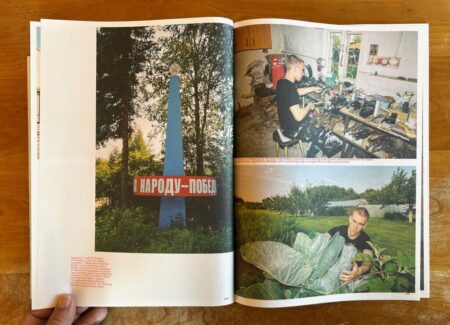

So far so good. But there is one more important dimension to the book. Gerzha’s photos were made in contemporary Russia. If youth culture is mysterious, Putin’s Russia is nearly a black box. External news coming into the country is tightly controlled. And messages to the outside world must be carefully parsed for information, like tea leaves or birth charts. For Gerzha, the Generational Theory of Strauss and Howe is another filter for analysis, tracking civilizations on a repeating cycle through periods of High, Awakening, Unraveling, and Crisis.

It’s not clear from Gerhza’s essay which generational cycle describes the Putin era. Somewhere between unraveling and crisis perhaps? In any case, the country presents an enigma to outsiders. Throw in an active plutocracy and “special military operation” and the tea leaves become even harder to read. Fresh conscripts must be drafted for the Ukraine invasion. The economy is stressed by sanctions and supply shocks. What’s a young person in Russia to do? What are they thinking? What is daily life like for them?

Tough questions. Luckily for readers, Gerzha is well qualified to explore them. She was born in 2003 in Russia, where she spent her childhood in Moscow and the nearby towns of Kolchugino and Lukhovitsy. In 2009 her world made an abrupt U-turn when her parents emigrated to the Netherlands. She then grew up in Amsterdam where, as described by The Eriskay Connection, she “was surrounded by her family’s Soviet mentality and traditions. From an early age, she began documenting the differences between these two cultures to understand why she did not feel fully at home in either.” Today she studies art history at the University of Amsterdam. From that home base, with a foot in both worlds, fluent in Russian and Dutch, she is uniquely positioned to investigate Russia—particularly its youth—as both an insider and an outsider.

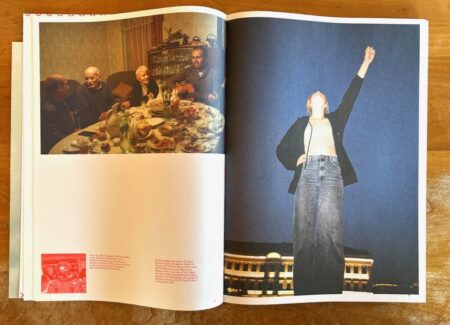

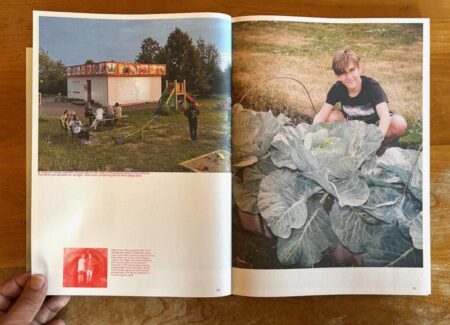

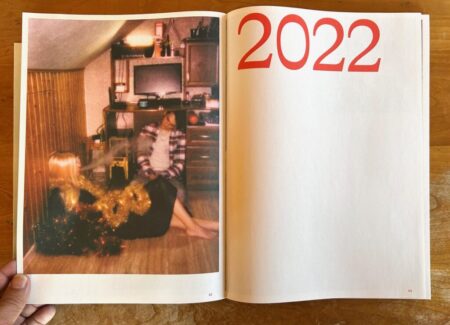

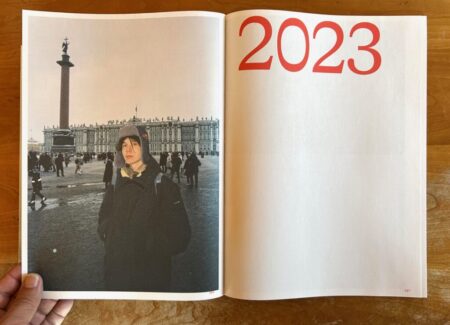

Gerzha made several forays into Russia over a three year period 2021-2023, meeting various young people, shooting photographs and conducting interviews. Control Refresh is structured as a chronology of her findings. It runs 160 pages, most of them dense with photos and texts. “New friends showed their vulnerability with me,” she writes. “They took me into their boredom and told me about their dreams and their lives, strangely influenced by traditions, social media, and politics.” Most subjects she photographed just once. Some reappear in multiple images through the book. All are funneled into three broad chapters, grouped by passing years: 2021, 2022, 2023. Annual breaks are denoted with bold red titles across double spreads. Within each year, varied layouts of photos, annotations, and contemporaneous events chart histories, both personal and Russian. Not only did the state undergo major turmoil between 2021-23, the period covered a sizable chunk of life for its adolescents.

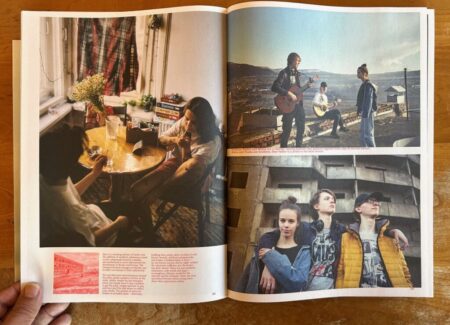

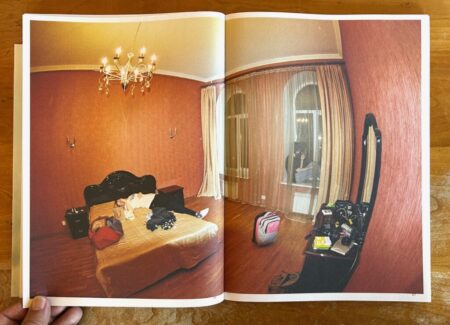

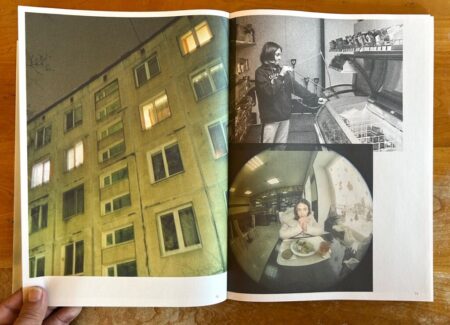

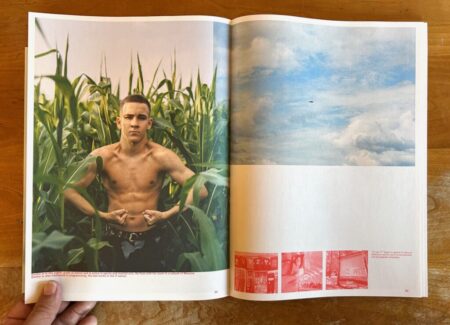

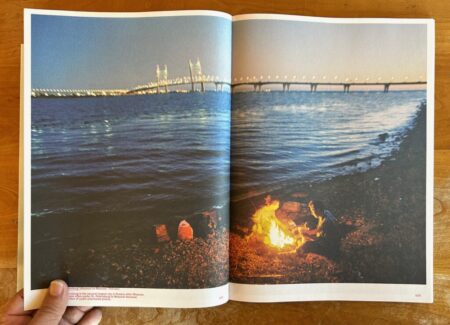

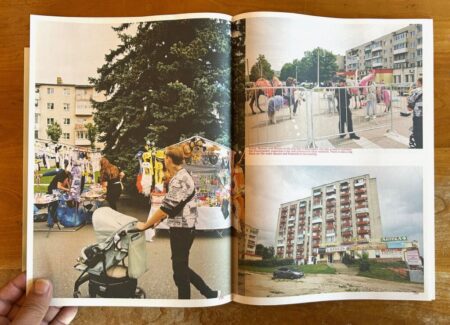

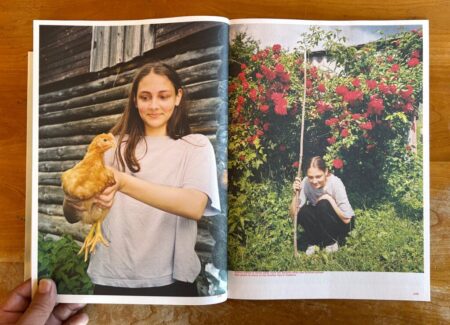

Gerzha’s photo style is loose and screen-friendly (she has almost 400K followers on Instagram). She uses small cameras handheld, capturing youth culture in the informal vein of Vinca Petersen, Shane Hallinan, or Maria Tomanova. Like many young people she hasn’t yet settled on a singular format—nor into a rut?—and her smorgasbord of treatments keeps the sequence fresh. Control Refresh flips between video stills, four-square grids, slow-synch flash, quick portraits, fisheyes, half-frames with sprocket holes, Polaroids, and more, skewing generally toward film. Is there anything she hasn’t tried? The book’s design supports the playful mood with magazine-style layouts, collage, and grids, all on thin-stock uncoated paper. Breezy might be an operative description.

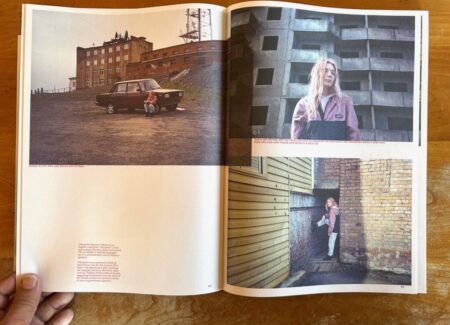

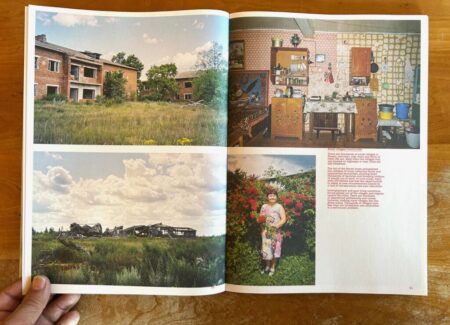

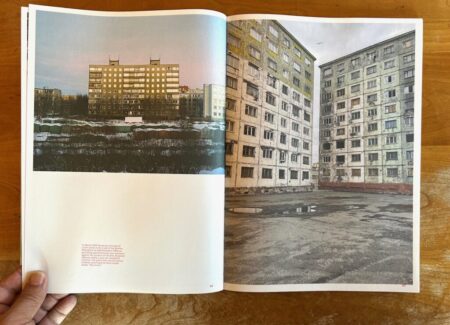

In broad strokes, the everyday activities of Russian youth look roughly similar to the adolescent ennui of their European cohort. Gerzha photographs twenty-somethings preening for her camera, hanging out at home, dating, playing music, loitering in malls, smoking, hunting vintage fashion, falling in love, working gig jobs, and busking at transit stops. One snap shows a young woman firing an arrow into a food freezer. Another captures weathered multistory apartments. When tedium builds to petty vice, they might tag walls with graffiti, climb roofs, or squat abandoned warehouses. The typical transgressions of bored teens.

It’s not clear how Gerzha met or selected her subjects, but in any case they are a weighted sampling. City residents are somewhat over-represented. According to Gerzha, they exemplify “Generation Z in the European sense (technologically educated progressive young people)”. Interspersed with the city dwellers are smatterings of small town life where, she explains, “no one is interested in this; people here have other issues: they focus on survival.” Comparisons to Rust Belt America are not far fetched.

All of which is to say, young Russians face the same general issues as young folks anywhere. How will they get an education? What will they do for work? Where will they live? How should they plan their relationships and family? Control Refresh presents some answers in the form of photo captions. “Ilya transferred to another university…Anya comes to visit on weekends,” says a typical description. “Yuliya and Roman are expecting a baby,” says another. “Roman wants to give his son the name Maxim.” Living arrangements are fraught, and finances force some youth into group living Kommunalkas. But even if circumstances are challenging, the worldview is generally forward. Better times ahead, hopefully.

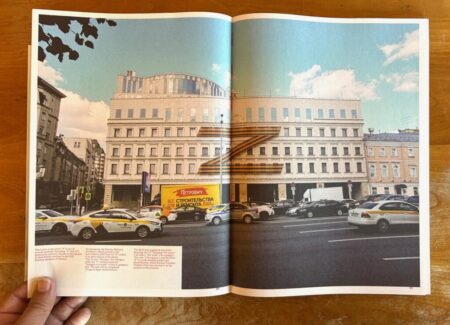

Gerzha’s writing voice is informative and photojournalistic, as if she is annotating an investigative expose. Meanwhile, small paragraph blocks—in a separate font for clarity—mark historic events along the book’s timeline. Gerzha notes a large pro-Navalny protest in 2021, the Ukraine invasion and Nationalistic Z symbols spouting up in 2022, anti-LGBTQ instructional reforms in 2023, and so on. Through these excerpts Gerzha’s political views become clear—she’s a Putin critic—but she is careful to describe events in a neutral tone.

Oddly, the concurrent text streams are divided. Photo captions and historic events co-exist across the pages, but without much interaction. Gen Z dreams of a better world, while the existing one reveals its many cracks. Gerzha describes current events. But, incredibly, none of her photo subjects comment on them directly. If they have ideas about Putin, Ukraine, Navalny, oligarchy, authoritarianism, or press restrictions, they are not expressed in the book. Even young men facing the stark choice of army vs. emigration do not seem angry at the state. Instead the tone is wary resignation. “We were all born in the era of Putin’s rule,” Gerzha explains. “In big Russian cities we try to oppose it, in small towns we become apolitical, because we believe that the change of power will not affect us in any way—there was ruin and there will be ruin.”

Perhaps the end result is the same. Fair enough. Still, the book’s even-handed tone is beguiling. I found myself reading between the lines. Where is that Rosetta Stone? What do the tea leaves say? Perhaps these young folks have learned to keep their mouths shut about politics? Or maybe those issues have been so whitewashed in Russia that they don’t feel pressing? Or perhaps Gerzha has edited the book with a deliberately objective tone, to weed out polemics and keep the focus on day-to-day concerns.

Whatever the reason, Control Refresh feels politically detached. Viewing its photographs, you’d hardly know the country is at war. Nor do the personal captions offer much inkling. If that seems an odd stance for a book about Russia, perhaps there is method to it. I’m an aging American, and my own views on Russia have admittedly been colored by years of Western media. Control Refresh presents a chance to step back, hit reset, put aside geopolitics for a moment, and open myself to Russia’s more prosaic activities. Perhaps this old-timer can learn a thing or two yet about youngsters in another country, and what makes them TikTok.

Collector’s POV: Toma Gerzha does not appear to have consistent gallery representation at this time. Collectors interested in following up should likely connect directly with the artist via her website (linked in the sidebar).

Great review, Blake! Imaginative and thoughtful.