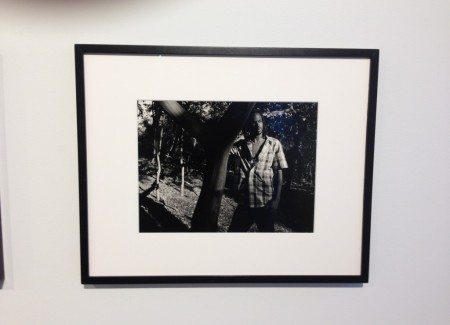

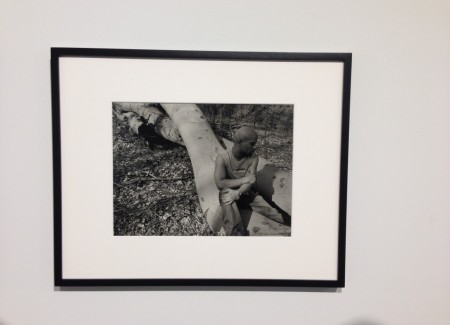

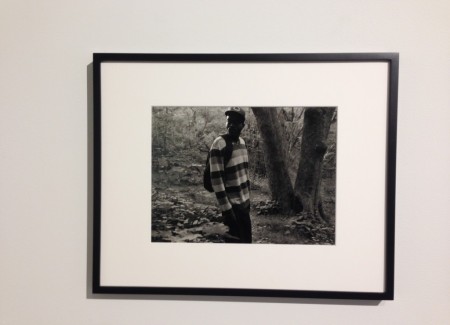

JTF (just the facts): A total of 67 black and white photographs, matted in black wooden frames and displayed on six outer walls and two inner walls of a partition in the main gallery space. All of the works are gelatin silver prints, made between 2008 and 2014. Physical sizes vary from 11×14 inches, to 16×20 inches, to 10×35 inches; all sizes are available in editions of 4+1AP. (Installation shots below.)

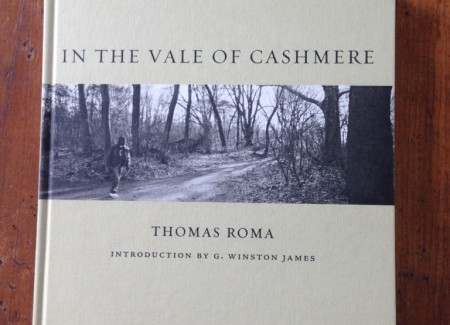

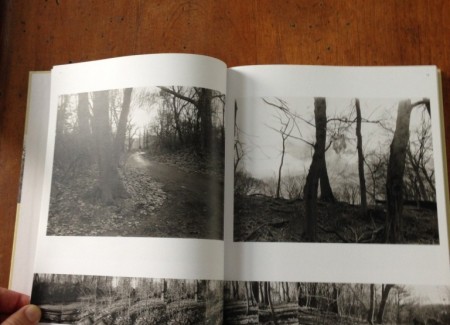

The exhibition appears in conjunction with a monograph published in 2015 by powerhouse Books (here). Hardcover, 7 ¼ x 9 ¼ inches, 144 pages, with 408 black-and-white photographic reproductions, and an introduction by G. Winston James. $30. (Cover and spread shots below.)

Comments/Context: Photographers as different as Ansel Adams and Garry Winogrand believed that answering the question “where do I stand?” was fundamental in taking pictures.

They meant, of course, not only what is the optimal position or angle to put my body and camera in order to get what I’m after, but also where should I stand as a social participant: what is the attitude I want my pictures to reveal or project about my relationship with my subject?

Braided issues of aesthetics and morality are notably hard to separate in portrait photography, a reciprocal human exchange that can result in a tug-of-war or a minuet. Charges of exploitation or sentimentalizing a subject or exoticizing “the other” perennially attend the process, and photographers have to be ready to meet them.

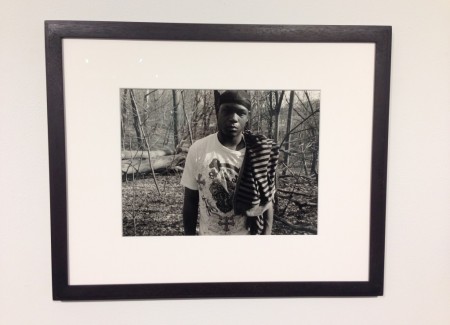

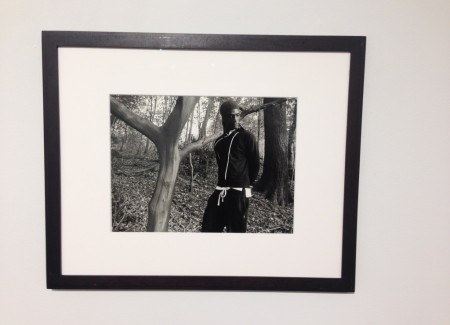

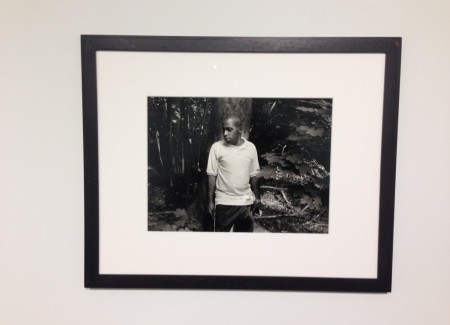

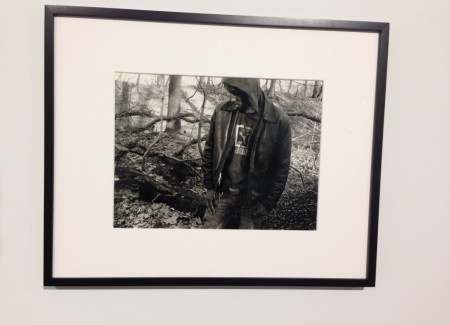

Thomas Roma spent five years photographing the male habitués who for decades have collectively (and secretly) regarded an area of Prospect Park, Brooklyn as a cruising zone. The redolent name for these woodsy paths in Frederick Law Olmsted’s 1867 design is “The Vale of Cashmere,” a name taken from a line by the Irish Romantic poet Thomas Moore.

As Roma is a white, middle-aged, Italian-American heterosexual family man and most of his subjects are young African-American or Latino gay or bisexual men engaged in furtive acts that at one time might have led to an arrest, a beating, or humiliation in the press, his first task was to earn their trust.

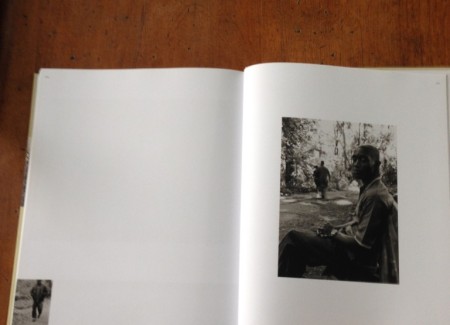

He has done this in two ways: first, by omitting their names (although presumably they realize that anyone seeing these photographs could identify them); and second, by omitting any sexual content from the portraits. Only the knowledge that this is a pick-up area allows us to group them together as men looking for partners; in every other respect they could be locals out for a jog or stopped on their way elsewhere. As posed portraits, these do not qualify as “street” photographs except in their lack of biographic information.

These decisions allowed Roma’s subjects better to gauge where he stood in connection to their reason for being in the park. His camera never intrudes, moving about them at a distance that changes between a few feet to a dozen yards. They look comfortable with him, to the extent that anyone discovered seeking a blowjob or intercourse in the open air can be said to feel secure in front of a stranger’s camera.

Were this scene or situation discovered by Diane Arbus or Sally Mann or Peter Hoeg or Roma’s former student Leigh Ledare, one can imagine the portraits would be more graphic and intimate but also more manipulated. Nothing here compares to the sensational photos made in 1979 by Kohei Yoshiyuki, whose voyeuristic bacchanal of coupling couples in two of Tokyo’s parks included roving hordes of male photographers sticking their cameras up the skirts of terrified half-clothed women.

Roma has the park to himself and his portraits are repressed by comparison. And yet what’s so moving about the series is the emotional spectrum visible in the men’s faces and postures. From his carefully negotiated distance, we are still privy to flickers of their lust. Some of his subjects maintain a wary and defensive stance; others are relaxed or defiant, unafraid to advertise their sexual availability. No doubt most were puzzled by his curiosity, or never lost their suspicions about his motives.

The series as a whole documents a battle within these men’s bodies between the fear of exposure and the desire for recognition. Are they emerging from the shadows as a statement, because they’re standing up for gay rights? Many of these men could never admit their desires to their families. Clandestine trysts outside their homes are the only safe way to express passion. And yet public acceptance may not be what they’re after. One shouldn’t forget that the dangers of having illicit sex with a stranger in a public place is for some men (and women) what makes such encounters irresistible.

The bosky surroundings and well-worn trails are not just backdrops but witnesses to these hook-ups. Roma photographs the park at different times of the year and day (although most often, it seems, late in the afternoon) and in the book, even more than the show, individual trees and clearings reappear like characters, much as they do in Atget’s forays around the old parks and forests surrounding Paris.

About half of the book are portraits of nature without people: close-ups of scarred bark; the sun weakly shining through bare branches; tiers of exposed roots polished by thousands of footsteps; the ground carpeted in leaves, strewn with clothes, newspapers, condom wrappers, and fallen apples. The sequencing of these images is particularly ingenious. Along with creating an unpredictable but coherent pattern on the white page, varying size and placement and moving between portraits and landscapes, Roma sets up a counter-rhythm at the bottom of many spreads with 12 joined thumbnails (6 to a page) that serve like a flip-book. There is even a “kicker,” a single 13th image on the following page. These smaller images, often picturing a man at a distance who moves closer and then out of the frame, give the book an extra boost of energy. Paths through the woods, they simulate what’s it’s like to observe and be observed, to pursue and be pursued.

In his fine introduction to the book, the Caribbean writer G. Winston James, himself a visitor to the Vale of Cashmere, lauds Roma for capturing “both the carnal and communal elements” of the place, and for “neither glorifying nor denigrating the men.” He notes that in New York, where space is at a premium and jealously guarded, for gay men to assemble in a park during the day was a declaration of solidarity. His sole note of lament is that none of the photographs were taken at night when the action really heats up, and that photographs can’t reproduce the ambiance of random sexual encounters in a park, “the sounds of the wind through the trees, of insects making their way through the detritus, of bats, footfalls, and moments of utter silence.”

As a friend of Roma who has spoken to his Columbia classes several times over the last 20 years, I may not be the most impartial critic of this work. But with this project and his recent Mondo Cane, he is in peak form. A photographer’s most difficult task is finding or choosing a subject suited to his or her talent, and this one is so charged with sexual and racial ions that everything could have gone explosively wrong. That it didn’t is a testament to the openness of these men, who elsewhere have something to hide, and also to Roma, who knows exactly how much can be said here without saying too much.

Collector’s POV: The works in this show are priced based on size: the 11 x 14 inch prints are $4500 each, the 16 x 20 inch prints are $5500, and the 10 x 35 inch prints are $5500. Roma’s work has little consistent secondary market history in the past decade, so gallery retail remains the best option for those collectors interested in following up.