JTF (just the facts): Published in 2014 by Phaidon Press (here). Hardcover (11 3/8 x 9 7/8), 304 pages, with 900 color illustrations, $100. (Spread shots below.)

Comments/Context: Of making many books about photobooks there is no end, or so it has seemed in the last decade. Since the turn of the millennium, new histories on this formerly arcane topic have appeared almost every year. Some have been international in scope, others were patriotic. There are now scholarly books on the Japanese, Latin American, Dutch, and Swiss photobook. With 192 countries in the world, the future of this sector in a depressed publishing economy looks surprisingly healthy.

So long as Martin Parr and Gerry Badger are tour guides to this expanding category, a lot of us will be happy to go along for the ride. Volume III of The Photobook: A History has arrived and it’s as enlightening and lively as the previous two. I would wager than no one alive except these two Englishmen has laid hands or eyes on, or even heard of, many titles here.

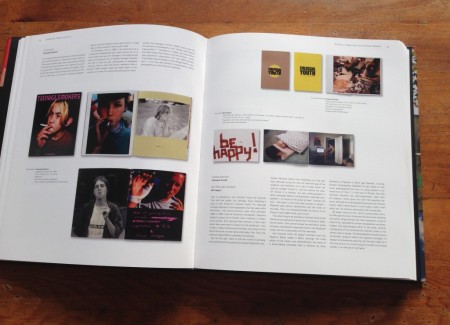

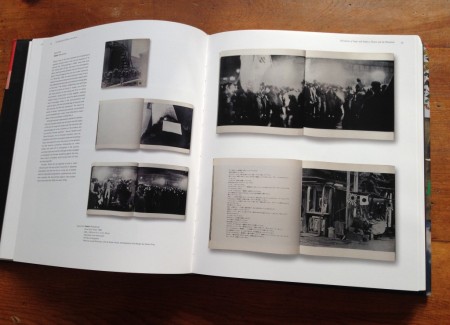

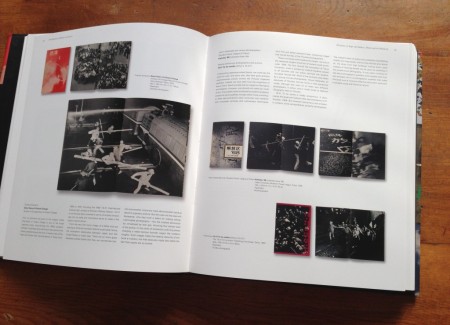

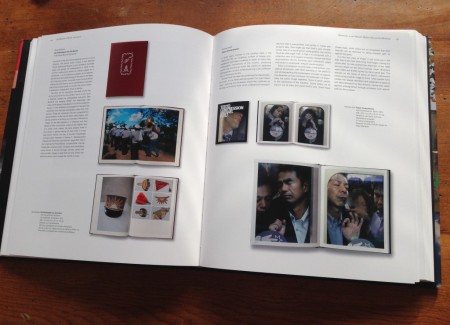

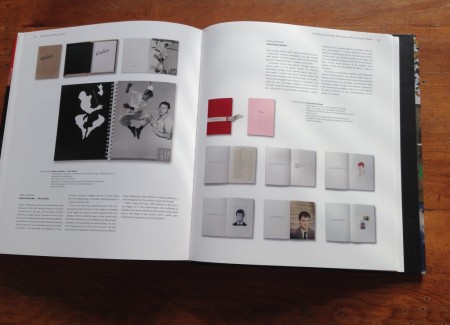

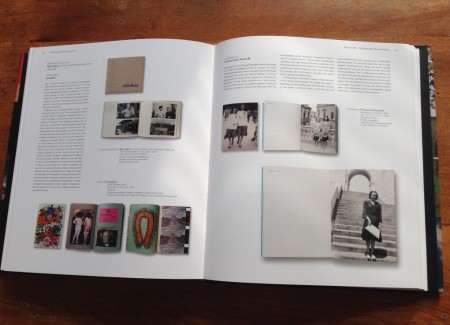

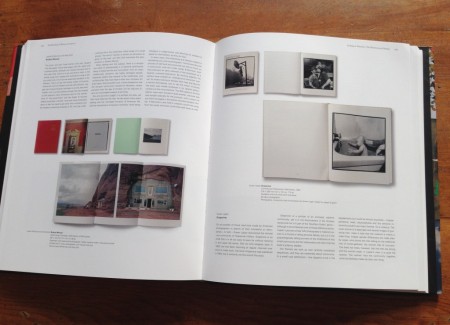

The focus on roughly 200 photobooks published between the 1930s and 2012 is narrower than in Volumes I and II. But all titles are treated in the same format as before, with no more than three per double-page spread. Accompanying a casual, informed description of the book’s contents—no more than 300 words on its history, ancestors, and progeny—are color reproductions of the cover and a few sample spreads. The generous amounts of white space gives an impression of roominess when in fact each write-up is extremely compact.

Once again, their history does not adhere to a chronology but is divided into nine themes. To their familiar interest in photography as propaganda–there are examples here from Portugal, Palestine, Israel, Algeria, Chile, Libya, East Germany, Nazi Germany, and Cuba–they have added chapters on sex and desire (in a chapter titled “The Kids are Alright,” after Ryan McGinley’s 2000 book); on the photographic book as political protest (“Documents of Anger and Sadness”); on self-portraits (“Looking at Ourselves”); on the ways photographs preserve or falsify a personal past or identity (“Memento Mori”); and on the post-modern movement of re-photography (“Cannibalizing Photography”).

Parr-Badger have done as much as anyone to focus attention on the many varieties of the Japanese photobook. All three volumes are rife with examples. I counted a dozen more here, including Kazuo Kitai’s Teikoh (Resistance) from 1965, a seminal book by a remarkable artist who underwent at least two distinct changes in style.

On the lookout for unusual items from anywhere, the authors can be counted on to shake up one’s preconceptions. I know nothing of a Czechoslovakian photographer named Jioi Putta, although I imagine him as someone who might have been a character in a Milan Kundera story. The full page devoted to his Katalog Masných Vyrobýo, Konsev a Salda (Catalogue of Meat Products, Conserves and Lard) suggests to Parr-Badger that in 1973 Putta decided to goof around with a dull Soviet -era commercial assignment by turning a platter of sausage, garnished with onion rings, a tomato, and parsley into an Arcimboldo.

No photobook history I have read has mentioned Teenage Styles and Trends 1967-71: a Retrospect by Burton Y Berry. Self-published in Zurich in 1972, it pretends to be a catalog of young people’s fashion. Behind this cover story it is actually a photo-book for a gay audience. Burton Y Berry was an American diplomat, now deceased, who made these amateur portraits when he was in his sixties. They reveal his lusty admiration for young men, then enjoying the freedom to dress more provocatively, and have much more sex, than he ever could when he was growing up.

Volume III has numerous other finds from might be called Outsider Photographers, but the concentration remains on those with official artistic credentials: Rinko Kawauchi, Paul Graham, Taryn Simon, Roger Ballen, Susan Meiselas, Guy Tillim, Alessandra Sanguinetti, Dinu Li, Pieter Hugo, Robert Heinecken, Leigh Ledare, Merry Alpern, Mark Steinmetz, Sophie Calle, Yto Barrada, Juergen Teller, John Stezaker, Michael Schmidt, Stephen Shore, Anthony Hernandez, Roe Ethridge, Christopher Wool, Richard Prince, Doug Rickard, and others. (I didn’t do a detailed gender breakdown but the numbers of titles represented skew heavily male.)

The ethical practice of critics touting books that they own has been questioned by several critics, including me. An endorsement by Parr-Badger is like an investing tip. Dozens of collectors have used their volumes, along with Andrew Roth’s The Book of 101 Books: Seminal Photographic Books of the Twentieth Century, as shopping lists. At times I have wondered if enthusiasm for certain titles might correspond with the number of out-of-print sale copies the authors have snapped up and stored away.

It’s hardly their fault, however, that the guides are so popular. Before these books, scholarly interest in the subject was confined to a few specialists in auction houses and museums. Parr-Badger have treated the photobook with respect, noting its special history, one that has developed parallel and separate from photography for galleries and magazines. Taking Americans out of their comfort zone, they aim to enlarge appreciation for photography books far beyond those select few produced for the art market on these shores. Both their politics and aesthetic is populist, in the left-of-center cultural studies mode that has flourished since the 1960s in British journalism.

In his introduction here, Parr writes that he and Badger have “always believed that our volumes act as a kind of unofficial revisionist history” of photography. I wouldn’t disagree. For decades Parr has scoured bookstores and bazaars in the dozens of countries he has visited on assignment as a photographer. As a result, he may possess more first-hand knowledge of the art and photojournalism scenes in more places than any curator in any museum. Although Parr and Badger were certainly not the first to celebrate the photobook’s unique lineage—Swann Galleries has devoted separate catalogs to photographic literature since 1981—the duo has given the genre a larger profile. As Parr writes here, it’s no longer odd in museum retrospectives to find vitrines of an artist’s books in the same room with his or her prints.

What Parr-Badger have not yet done, though, is rigorously prune their shelves. If they want to see themselves as unofficial curators of the genre, then they need to make some tough and, no doubt, controversial judgments. The history of art is not a democracy in which every photo is as good as every other. It’s easy to be a revisionist if all you do is permit a lot of titles into your history that earlier writers ignored or excluded. By allowing into their Volumes any book that intrigues or amuses them, or that has an outré or political edge, they have shied away from having to defend which ones are the most vital and why some (and not others) have had—or should have—lasting influence. Maybe they can perform that essential job as their encore for Volume IV.