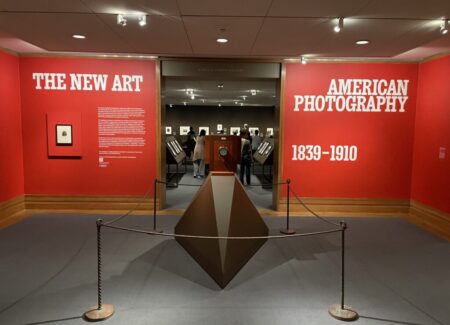

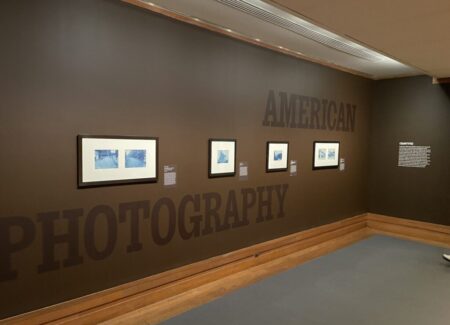

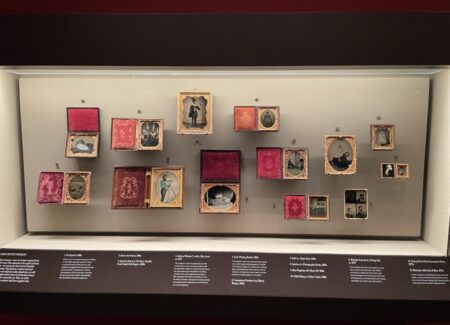

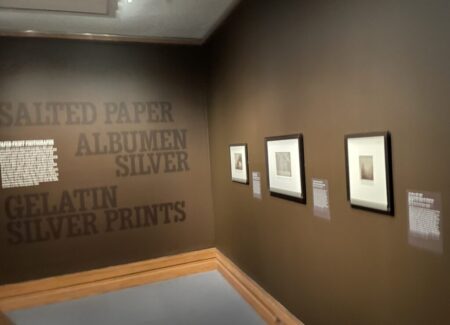

JTF (just the facts): An extensive group show, consisting of roughly 275 photographs, installed against red and brown walls, and in various cases, in a series of three rooms on the museum’s second floor. The exhibit was curated by Jeff Rosenheim with assistance by Virginia McBride. (Installation shots below.)

The following works are included in the show:

Introduction (entry area)

- Unknown maker: 1 salted paper print from glass negative, c1855, sized roughly 5×4 inches

- E. and H. T. Anthony: 1 wood, brass, and glass camera, c1877

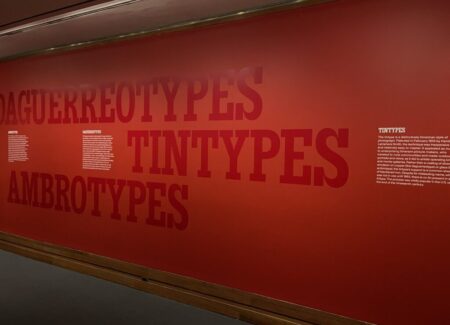

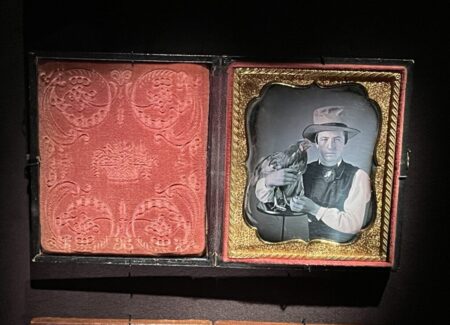

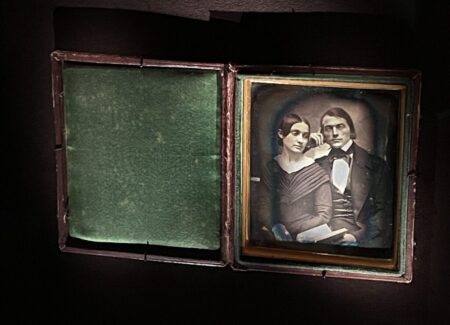

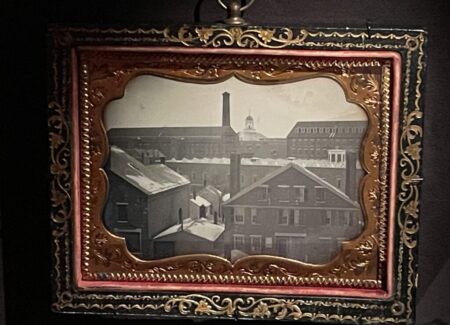

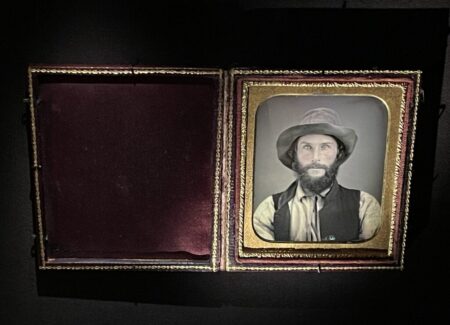

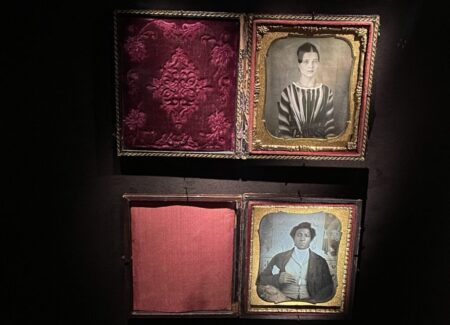

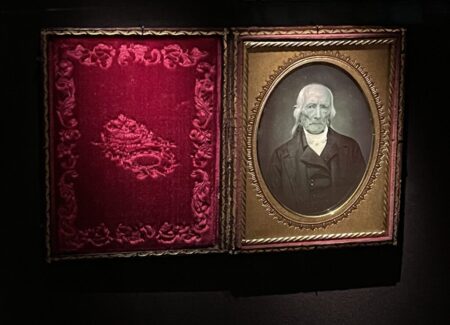

Daguerreotypes (room 1)

- Thomas H. Darling: 1 daguerreotype, 1840-1842, sized roughly 7×3 inches

- Edward Sidney Dunshee: 1 daguerreotype, 1845, sized roughly 4×3 inches

- Alexander Beckers: 1 daguerreotype with applied color, 1853-1858, sized roughly 5×8 inches

- Theodore Harris: 1 daguerreotype, 1853-1855, sized roughly 4×6 inches; 1 set of 3 daguerreotypes, 1854-1857, sized roughly 5×7 inches

- R.G. Montgomery: 1 daguerreotype with applied color, c1850, sized roughly 7×5 inches

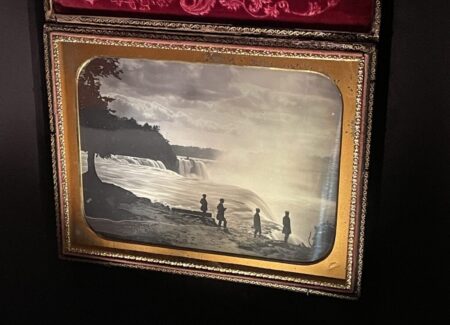

- Platt D. Babbitt: 1 daguerreotype, 1853-1858, sized roughly 14×9 inches

- D. Dennison Cone: 1 daguerreotype, c1850, sized roughly 6×4 inches

- George Gilchrest: 1 daguerreotype, 1856, sized roughly 4×5 inches

- Nathaniel Crosby Jaquith: 1 daguerreotype, 1849-1857, sized roughly 4×6 inches

- Marcus Aurelius Root: 1 daguerreotype, 1845-1856, sized roughly 4×6 inches

- Unknown makers: 14 daguerreotypes, 1842-1845, mid-late 1840s, c1850, 1853, 1850s, sized roughly 10×6, 7×5, 7×3, 6×5, 5×12, 5×8, 5×7, 5×4, 4×5, 4×6, 3×5, 3×4 inches

- Unknown makers: 24 daguerreotypes with applied color, 1842-1845, c1848, late 1840s, c1850, early 1850s, 1850s, 1856-1857, sized roughly 10×6, 8×19, 7×5, 6×4, 5×4, 5×7, 4×7, 4×6, 4×3, 3×4 inches

- Unknown maker: 1 rosewood, brass, ivory, and glass camera, c1845, sized roughly 6x6x14 inches

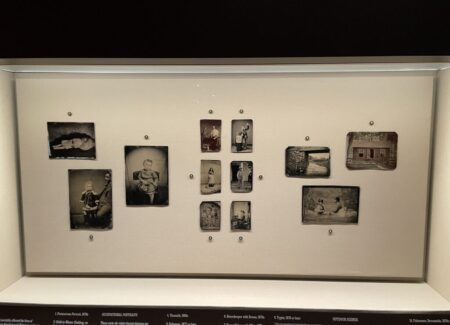

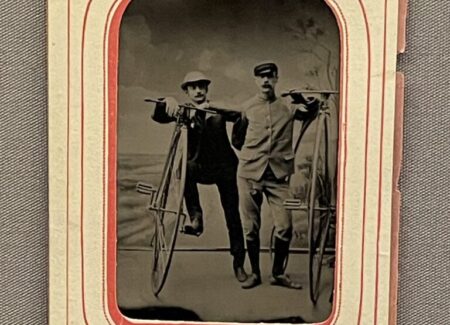

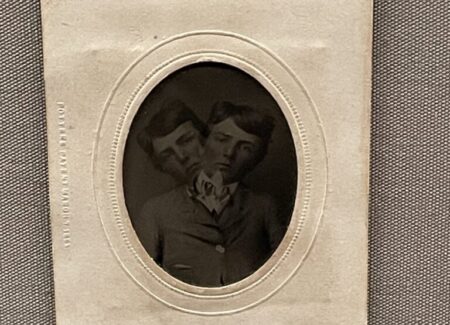

Tintypes (room 1)

- Charles H. Gallup: 1 tintype, 1885-1890, sized roughly 5×3 inches

- C.H. Palmer: 1 tintype with applied color, 1889, sized roughly 4×3 inches

- Ellen M. Myers: 1 tintype, c1880, sized roughly 3×2 inches

- John Holyland: 1 tintype with applied color, 1865-1870, sized roughly 2×1 inches

- Golder & Robinson: 3 tintypes with applied color, 1870s, sized roughly 4×3, 4×2 inches

- Nereus Baldwin: 1 tintype, 1870s, sized roughly 3×2 inches

- Unknown makers: 40 tintypes, 1860s, 1860s-1880s, c1870, 1877, 1878, 1870s, 1870s-1880s, 1870s-1890s, c1880, c1890, 1890-1898, sized roughly 10×6, 9×7, 8×7, 7×9, 7×8, 7×5, 6×8, 6×5, 5×8, 5×7, 5×6, 5×3, 4×6, 4×5, 4×3, 4×2, 3×4, 3×2 inches

- Unknown makers: 16 tintypes with applied color, 1860s, c1870, 1870s, 1870s-1880s, 1880s, 1880s-1890s, sized roughly 15×12, 9×7, 6×10, 6×5, 5×4, 4×6, 4×3, 3×2, 2×4, 2×3, 2×1 inches

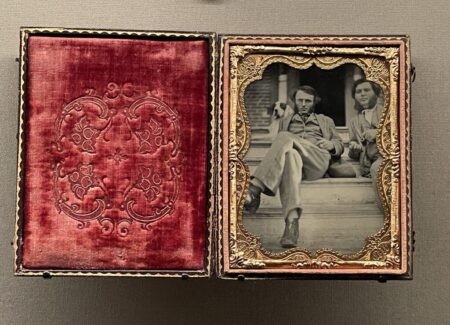

Ambrotypes (room 1)

- Unknown makers: 4 ambrotype, 1860s, c1865, sized roughly 8×6, 8×3, 5×7 inches

- Unknown maker: 1 ruby-glass ambrotype, c1870, sized roughly 5×7 inches

- Unknown makers: 2 ambrotypes with applied color, 1860s, sized roughly 4×7, 4×3 inches

Paper Prints (room 2)

- James E. McClees, Charles Ehrmann, Martin M. Lawrence: 1 crystalotype (salted paper print from glass negative), c1854, sized roughly 7×9 inches

- Josiah Johnson Hawes: 1 salted paper print from glass negative, early 1850s, sized roughly 7×9 inches

- John Moran: 2 albumen silver prints from glass negatives, early 1860s, 1861-1862, sized roughly 8×5, 5×4 inches

- O.B. Buell: 1 albumen silver print from glass negative, 1860s-1870s, sized roughly 8×7 inches

- Alice Austen: 1 albumen silver print from glass negative, 1888, sized roughly 6×8 inches

- Mathew B. Brady: 1 albumen silver print from glass negative, 1861, sized roughly 11×15 inches

- Alexander Gardner: 2 albumen silver prints from glass negatives, 1862, 1865, sized roughly 7×9, 7×5 inches

- Andrew J. Russell: 3 albumen silver prints from glass negatives, 1863-1865, 1864, 1867, sized roughly 9×12, 9×13, 10×13 inches

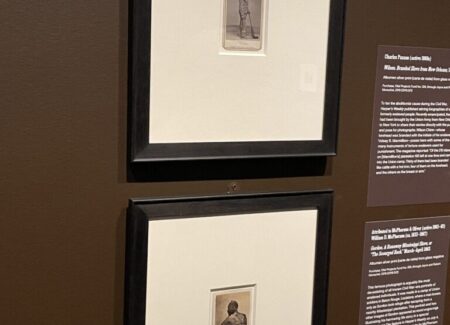

- Charles Paxson: 1 albumen silver print from glass negative, 1863, sized roughly 3×2 inches

- McPherson & Oliver: 1 albumen silver print from glass negative, 1863, sized roughly 4×2 inches

- George N. Barnard: 1 albumen silver print from glass negative, 1866, sized roughly 10×14 inches

- Anna K. Weaver: 1 albumen silver print from glass negative, 1874, sized roughly 11×18 inches

- Bendann Brothers: 1 albumen silver print from glass negative, 1870, sized roughly 8×6 inches

- Carleton E. Watkins: 3 albumen silver prints from glass negatives, c1863, 1873-1874, sized roughly 12x1o, 5×6 inches

- Edward H. Fox: 1 albumen silver print from glass negative, 1870s-1880s, sized roughly 5×8 inches

- Haroun and Bierstadt: 1 artotype (collotype from glass negative), 1882, sized roughly 7×5 inches

- Henry C. Tibbitts: 1 gelatin silver print, 1910, sized roughly 6×8 inches

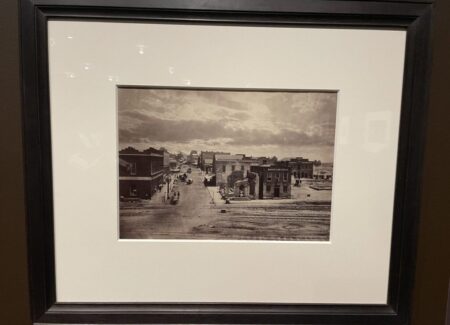

- George C. Bennett and William Henry Brown: 1 albumen silver print from glass negative, 1880s, sized roughly 4×5 inches

- George Egbert Mellen: 1 albumen silver print from glass negative 1884 or later, sized roughly 5×7 inches

- James W. Williams: 1 talbotype (salted paper print from glass negative) with applied color, late 1850s, sized roughly 12×10

- Lewis Dowe: 2 albumen silver prints from glass negatives, 1865, sized roughly 6×8 inches

- James Fitzallen Ryder: 1 albumen silver print from glass negative, 1863, sized roughly 7×9 inches

- Thomas C. Roche: 1 albumen silver print from glass negative, 1865, sized roughly 3×6 inches (shown in vintage stereopticon)

- Unknown makers: 6 albumen silver prints from glass negatives, c1870, c1880, 1885, 1890s, sized roughly 4×8, 5×7, 8×6, 8×10, 9×15 inches

- Unknown maker: 1 cyanotype, 1893, sized roughly 8×6 inches

- Unknown maker: 1 salted paper print from paper negative, c1857, sized roughly 5×7 inches

- Unknown makers: 2 salter paper prints from glass negatives with applied color, 1860s, sized roughly 9×7 inches

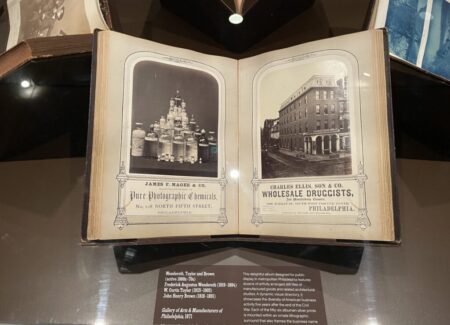

- (vitrine) Wenderoth, Taylor & Brown: albumen prints from glass negatives, 1871, sized roughly 14×10 inches

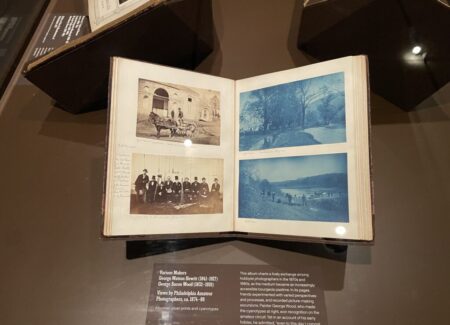

- (vitrine) George Watson Hewitt and George Bacon Wood: albumen prints, platinum prints, cyanotypes, c1874-1899, sized roughly 11×9 inches

- (vitrine) Unknown maker: platinum prints, 1897, sized roughly 10×12 inches

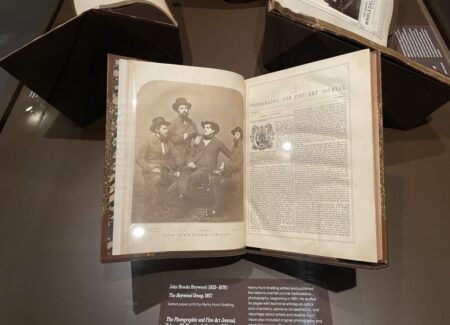

- (vitrine) Photographic and Fine Art Journal: salted paper print from glass negative, 1858, sized roughly 13×10 inches

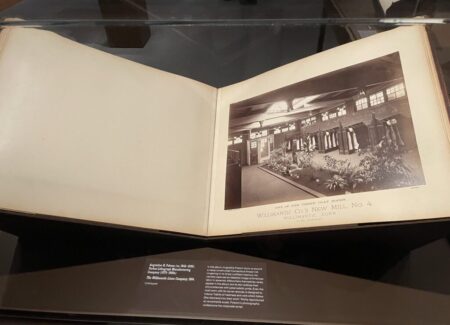

- (vitrine) Augustine H. Folsom: collotypes, 1884, sized roughly 18×22 inches

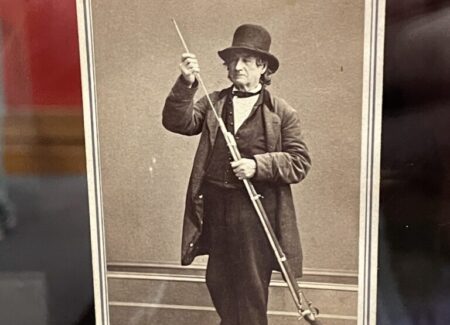

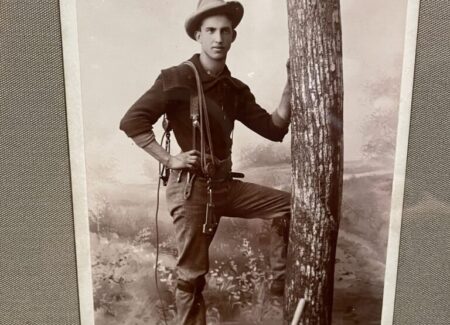

Cartes de Visite (room 3)

- J. Gurney & Son: 1 albumen silver print from glass negative, 1864, sized roughly 4×2 inches

- Richard A. Lewis: 1 albumen silver print from glass negative, 1860s, sized roughly 4×2 inches

- Christopher Columbus Sherwood: 1 albumen silver print from glass negative, 1860s, sized roughly 4×2 inches

- Tappin’s Photograph Art Gallery: 1 albumen silver print from glass negative, 1861-1865, sized roughly 4×2 inches

- G.F. Child: 1 albumen silver print from glass negative, 1865, sized roughly 4×2 inches

- John S. Myers: 1 albumen silver print from glass negative, 1864-1866, sized roughly 4×2 inches

- Elisha Couchman: 1 albumen silver print from glass negative, 1864-1866, sized roughly 4×2 inches

- Carl Casper Giers: 1 albumen silver print from glass negative, 1866, sized roughly 3×2 inches

- George Stacy: 1 albumen silver print from glass negative, 1864, sized roughly 4×2 inches

- Charles DeForest Fredericks: 2 albumen silver prints from glass negatives, 1860s, c1864, sized roughly 4×2 inches

- Silsbee, Case & Company: 1 albumen silver print from glass negative, 1862, sized roughly 3×2 inches

- J.H. Dodge: 1 albumen silver print from glass negative, 1860s, sized roughly 4×2 inches

- W.T. Seeley: 1 albumen silver print from glass negative, 1865, sized roughly 4×2 inches

- William Shew: 1 albumen silver print from glass negative, 1860s, sized roughly 4×2 inches

- S. Spitzer: 1 albumen silver print from glass negative, 1868 or later, sized roughly 4×2 inches

- Thomas J. Merritt: 1 albumen silver print from glass negative, c1864, sized roughly 4×2 inches

- Gottschalk Grelling: 1 albumen silver print from glass negative, 1864-1866, sized roughly 4×2 inches

- Meske, Gilman & Morris: 1 albumen silver print from glass negative, 1860s, sized roughly 4×2 inches

- Gillett & Paxson: 1 albumen silver print from glass negative, 1860s, sized roughly 4×2 inches

- Richard A. Lewis: 1 albumen silver print from glass negative, 1860-1865, sized roughly 4×2 inches

- N.W. Pease: 1 albumen silver print from glass negative, 1865-1870, sized roughly 3×2 inches

- Haines & Wickes: 1 albumen silver print from glass negative, late 1860s, sized roughly 2×4 inches

- Eadweard Muybridge: 1 albumen silver print from glass negative, 1868, sized roughly 4×2 inches

- Louis de Planque: 1 albumen silver print from glass negative, c1867, sized roughly 4×2 inches

- Carleton E. Watkins: 1 albumen silver print from glass negative, 1862-1863, sized roughly 2×4 inches

- A.C. Townsend: 1 albumen silver print from glass negative, 1865-1867, sized roughly 2×2 inches

- Willam F. Osler: 1 albumen silver print from glass negative, 1869, sized roughly 4×2 inches

- J.P. Vail: 1 albumen silver print from glass negative, 1864-1866, sized roughly 4×2 inches

- William Dickman: 1 albumen silver print from glass negative, 1865-1867, sized roughly 4×2 inches

- H.T. McCormick: 1 tintype, 1870s, sized roughly 2×2 inches

- Richard Garrison Barcalow: 1 albumen silver print from glass negative, late 1860s, sized roughly 3×2 inches

- R.W. Ransom: 1 albumen silver print from glass negative, 1860s, sized roughly 4×2 inches

- Twining & Twiford’s Gallery: 1 albumen silver print from glass negative, 1865-1866, sized roughly 4×2 inches

- Samuel J. Mason: 1 albumen silver print from glass negative, 1860s, sized roughly 2×4 inches

- Charles G. Crane: 1 albumen silver print from glass negative, c1866, sized roughly 4×2 inches

- Fred S. Crowell: 1 albumen silver print from glass negative, c1869, sized roughly 2×4 inches

- Jackson Brothers: 2 albumen silver prints from glass negatives, 1867-1869, sized roughly 4×2 inches

- Whitney’s Gallery: 1 albumen silver print from glass negative, c1862, sized roughly 4×2 inches

- Unknown makers: 5 albumen silver prints from glass negatives, 1860s, 1864-1866, 1864-1868, c1870, sized roughly 4×2, 3×2 inches

- Unknown makers: 3 tintypes, 1869s, 1860s-1870s, 1873, sized 2×2, 2×1 inches

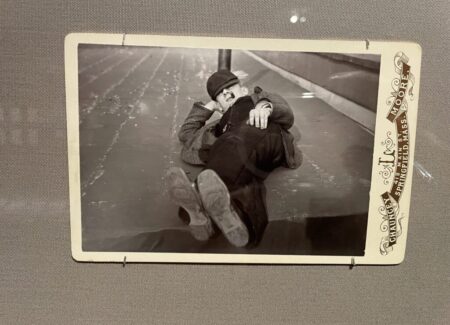

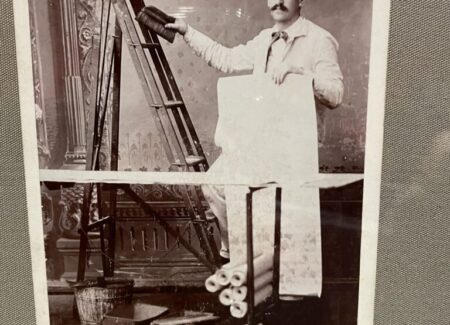

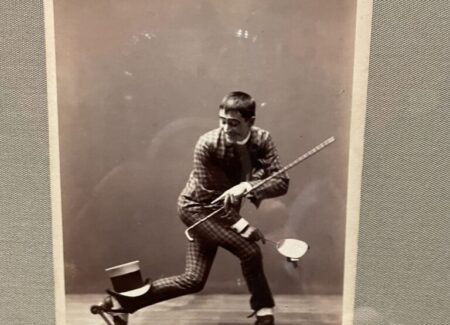

Cabinet Cards (room 3)

- Chauncey L. Moore: 1 albumen silver print from glass negative, 1880-1890s, sized roughly 4×6 inches

- Charles Miller: 1 gelatin silver print from glass negative, c1890, sized roughly 4×6 inches

- Emma I. Kemp: 1 gelatin silver print from glass negative, 1892-1894, sized roughly 4×6 inches

- Gilbert & Bacon: 1 albumen silver print from glass negative, 1880-1886, sized roughly 6×4 inches

- E.B. Champion: 1 gelatin silver print from glass negative, 1890s, sized roughly 7×4 inches

- Reed I. Case: 1 gelatin silver print from glass negative, 1890s, sized roughly 7×4 inches

- Charles B. Tripp: 1 albumen silver print from glass negative, 1885, sized roughly 6×4 inches

- Charles A. Millard: 1 albumen silver print from glass negative, 1880s, sized roughly 6×4 inches

- A.H. Dinsmore: 1 albumen silver print from glass negative, c1890, sized roughly 5×4 inches

- Andrew Miller: 1 albumen silver print from glass negative, 1880s, sized roughly 4×6 inches

- National Photographic View Co.: 1 albumen silver print, 1880s, sized roughly 6×4 inches

- Unknown maker: 1 albumen silver print from glass negative, c1890, sized roughly 7×4 inches

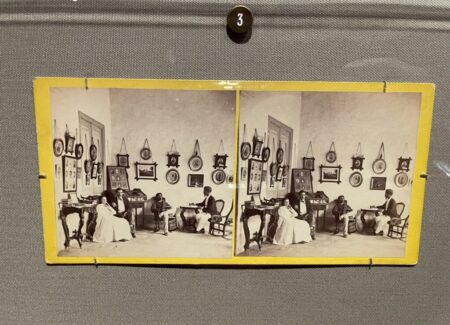

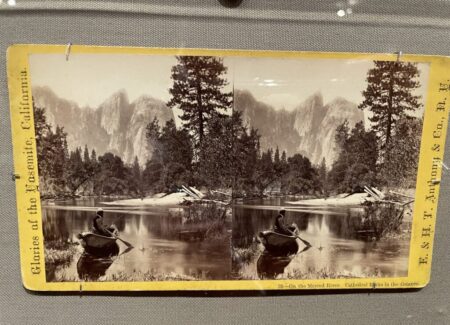

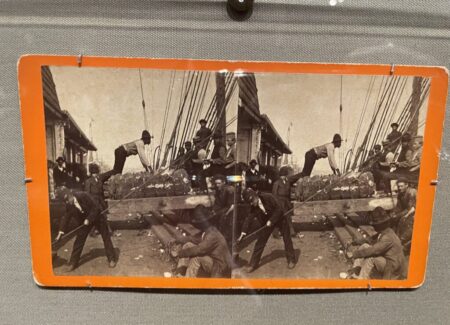

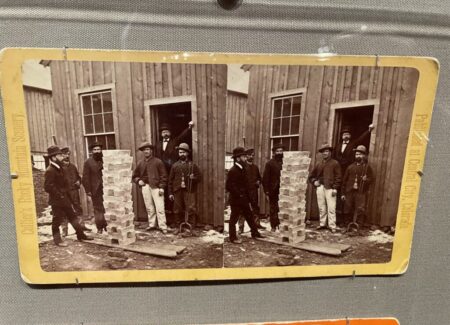

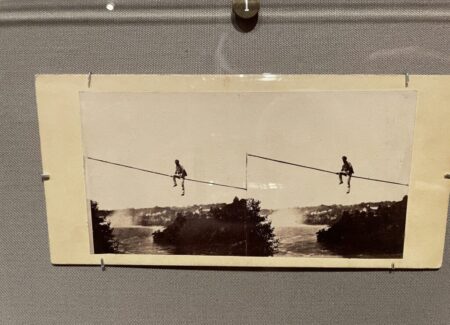

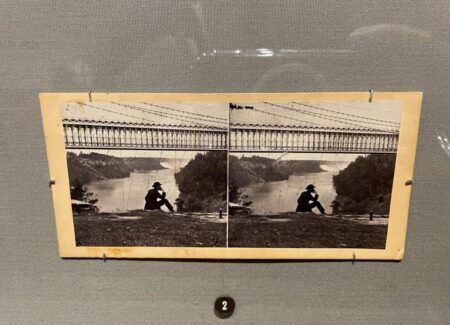

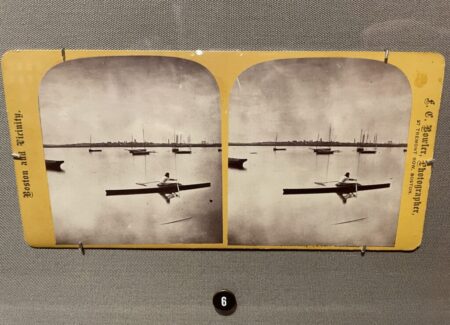

Stereographs (room 3)

- John Emmons Whitney: 2 albumen silver prints from glass negatives, 1862-1867, 1862-1868, sized roughly 3×3 each

- William H. Jacoby: 1 albumen silver prints from glass negative, late 1860s, sized roughly 3×3 each

- A.S. Taylor Jr.: 1 albumen silver prints from glass negative, c1870s, sized roughly 3×3 each

- Bartlett, French & Smith: 2 albumen silver prints from glass negatives, late 1860s, sized roughly 3×3 each

- William F. Larrabee: 1 albumen silver prints from glass negative, c1870, sized roughly 3×3 each

- James E. Irving: 1 albumen silver prints from glass negative, late 1860s, sized roughly 3×3 each

- E. & H.T. Anthony: 7 albumen silver prints from glass negatives, 1859, 1859-1862, 1863, 1865, 1870-1871, sized roughly 4×3, 3×3 each

- O. Pierre Havens: 1 albumen silver prints from glass negative, c1880, sized roughly 4×3 each

- James A. Palmer: 1 albumen silver prints from glass negative, 1870s, sized roughly 3×3 each

- John Collier: 1 albumen silver prints from glass negative, 1871-1877, sized roughly 4×3 each

- L.T. Sparhawk: 1 albumen silver prints from glass negative, 1870s, sized roughly 4×3 each

- Samuel Root: 1 albumen silver prints from glass negative, 1860s, sized roughly 3×3 each

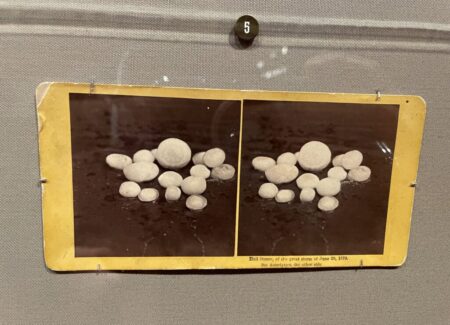

- Lewis M. Rutherford/Sigmund Beer: 1 albumen silver prints from glass negative, 1861, 1862, sized roughly 3×3 each

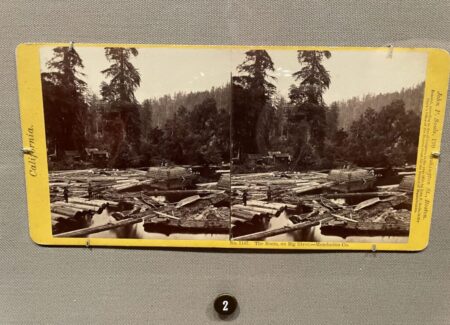

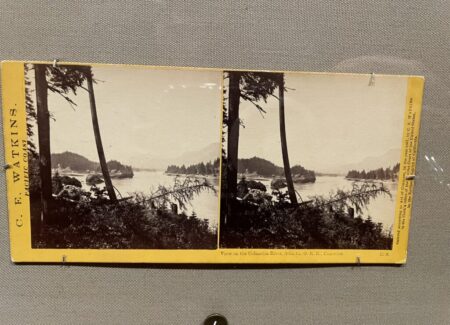

- Carleton E. Watkins: 1 albumen silver prints from glass negative, 1867, sized roughly 3×3 each

- Knowlton Brothers: 1 albumen silver prints from glass negative, 1870, sized roughly 3×3 each

- Thomas Houseworth & Co.: 1 albumen silver prints from glass negative, 1860s, sized roughly 3×3 each

- P.C. Bowler: 1 albumen silver prints from glass negative, 1867-1870, sized roughly 3×3 each

- Unknown makers: 6 albumen silver prints from glass negatives, 1861, c1863, 1864, 1866 or later, 1870, c1880, sized roughly 4×3, 3×3 each

- Scovill Manufacturing Co.: wood, brass, and glass stereo camera, 1880s, sized roughly 58x9x25 inches

- (selection of digitized stereographs presented in period stereopticon)

Cyanotypes (external hallway walls)

- R.A. Beck: 2 cyanotypes, 1892, sized roughly 8×10 inches

- Unknown makers: 9 cyanotypes, 1890s, 1895, 1896, c1900, 1904, 1905, 1906, 1907, sized roughly 6×8, 6×9, 7×8, 7×9, 8×9, 8×10 inches

Comments/Context: When we visit an art museum to take in a broad survey exhibition, of works made in a period of time, in a particular medium, and in a particular geography (like Dutch paintings from the 17th century for example), we are typically presented with a chronological structure that is anchored by the work of a few key artists. In this way, the wider arc of art history becomes a distinct progression defined by selected names, where we jump from one notable artist to the next (from Rembrandt to Hals to Vermeer and others), following how certain works reflect their unique insights and innovations. When a curator ties this all together into a neat package, we come out with a simplified summary of sorts, that hits memorable artistic high points and draws key conclusions (with the benefit of hindsight) about how it all fits together.

So when we turn our attention to 19th century American photography, there is of course a similar kind of art historical synopsis that can be derived. Given that the earliest forms of photography were largely discovered and commercialized first in Europe, the high level story of 19th century photography tends to have a French and British bias, with many intrepid experimenters chasing the same technical problems at the same time, and then heading off to document with world (particularly to Grand Tour destinations in southern Europe, the Middle East, and Egypt) with their newfangled (and often unwieldy) technologies. The American version of the story is then one of waves of these new photographic approaches arriving here and being adapted to the needs of the local populace. And when we build a thumbnail history of 19th century American photography, again hung on an organizing framework of famous artistic names, we typically start with the daguerreotype portraits of Southworth & Hawes, followed by the Civil War photography of Brady, Gardner, Barnard, and Russell, the Western survey photography of Watkins, Muybridge, O’Sullivan, and Jackson, and ultimately onward to the bridge to the 20th century as provided by the likes of Stieglitz, Käsebier, Coburn, and White.

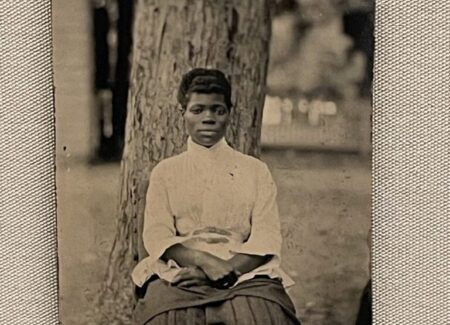

And while many of those bold faced names do appear here and there in The New Art: American Photography, 1839-1910, they’re not singled out or highlighted in this presentation as linchpins to our understanding of the artistic period. Instead, the show provides an alternate reading of the photographic 19th century in America, offering a view of an ever changing medium that was slowly being embraced by the democratic many, rather than an esoteric art form reserved for only the privileged few. As such, this exhibit reads like an opposing vantage point into this uniquely American photographic history, one where we essentially leave out the well worn paths of the acknowledged masters and instead investigate what we can learn about this country (and its interests in the new medium) from an aggregation of superlative examples made by relative unknowns and now forgottens. Given the gloriously eclectic quality of what’s included here, that story turns out to be quite a bit richer and more exhilarating than we might have ever expected.

At its core, this is a straightforward collection show – an exhibit put on by the museum to celebrate the new acquisition of a large art collection. Back in early 2020, Met trustee Philip Maritz and his wife Jennifer assisted the museum in the acquisition of some 700 works from the massive collection of long time private dealer William Schaeffer, as part of the larger gifts and celebrations surrounding the museum’s 150th anniversary. Those promised gifts have now been slimmed down into a somewhat narrower (but still altogether robust) presentation by Met curator Jeff Rosenheim, adding a second pass of editing and shaping to the initial effort made by Schaeffer himself over the span of nearly 50 years.

Given that so many of the undeniably great works in the Schaeffer collection were made by now obscure or anonymous photographers, it’s decently obvious that Rosenheim couldn’t practically choose an artist-driven structure for this show – there is far too much uncertainty (and mystery) about who are artists actually were to make their individual merits the centerpiece of his curatorial thesis. Instead, he has chosen a process-centric framework, where different kinds of photographs, from daguerreotypes and tintypes to paper prints, cartes de visite, and stereographs (among others), are explored discretely and sequentially, with the larger chronology of photography (across roughly seventy years) pulled along by these various incremental technical advances. This organization underplays the “who” of the makers, uses the “how” of the photographic processes as a timeline, and then turns our attention to the “what” of the image content, and what it can tell us about the evolution of American identity.

Like any technology adoption story, the path of 19th century photography in America is essentially a better, cheaper, faster narrative. What’s perhaps more durably important than how one approach specifically improved on its predecessors is how when we transition from the daguerreotype through the many process that came later, photographs are getting easier and more convenient to make (by a wider range of makers in a wider range of locations beyond the confines of the studio), cheaper to make, faster to make, and easier to distribute more widely as prints and keepsakes, which leads to much broader adoption of the technology over time. And as the use of photography becomes more prevalent (we might more formally call this the “expansion of access”), the subject matter of the resulting pictures also changes – when it becomes easier and cheaper to make pictures, the improvisational creativity of what merits being photographed (as decided by whoever is behind the camera) similarly expands.

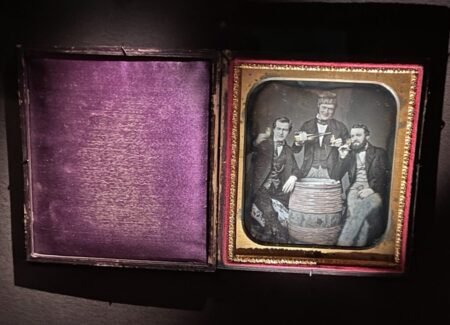

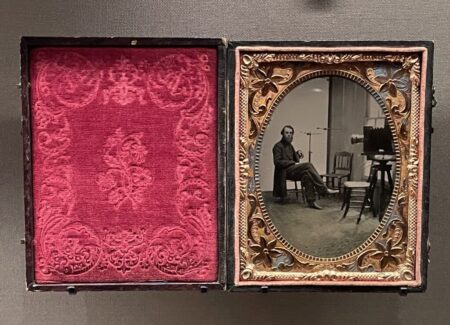

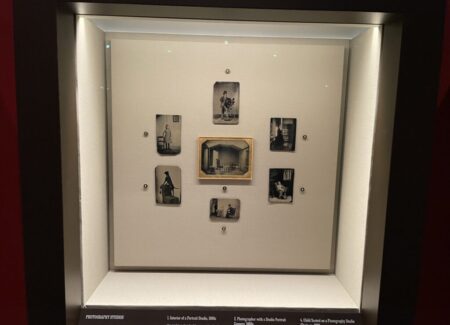

This story begins with the Louis Daguerre’s invention of the daguerreotype, and its subsequent arrival in America in 1839. The Schaeffer collection is well stocked with fine examples from the 1840s and 1850s, displayed here in intricately lit free-standing cases. Given their highly polished mirrored surfaces, daguerreotypes are notoriously difficult to display, and the Met deserves particular accolades for their efforts to light these intimate objects without reflection or shadow – it’s as masterful an exhibition of daguerreotypes as I have ever seen. The process itself involves polished silver plates, mercury vapors, and other fuming and chemical steps, so it’s not entirely surprising that many of the daguerreotypes on view here are portrait subjects and views of other controlled studio environments. As expected, some of the early adopters of this technology were the wealthy and privileged, as seen in their formal suits, frock coats, and elaborate dresses. But Schaeffer’s collection quickly moves on from these straightforward portraits, in search of more eclectic vernacular American subjects and personalities. Standout images feature the faces of a group of wine drinkers, a man with a rooster, a blacksmith with an anvil, and the nested image of a boy holding a daguerreotype in his hand. The selections also start to show us the contours of what Americans felt compelled to photograph, when first given the opportunity: loved ones, post mortem views of young children, prized rose gardens, horses, and pets, and of course, Niagara Falls.

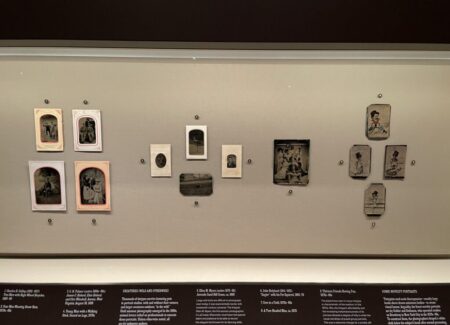

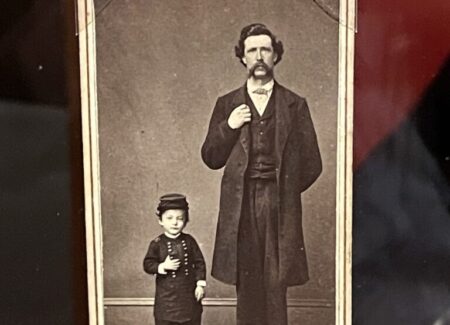

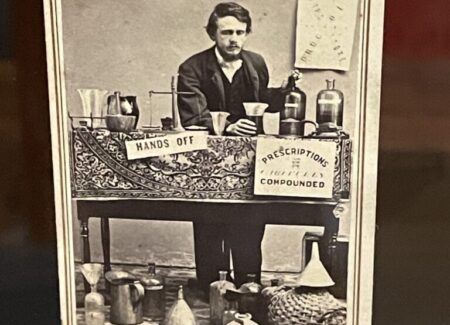

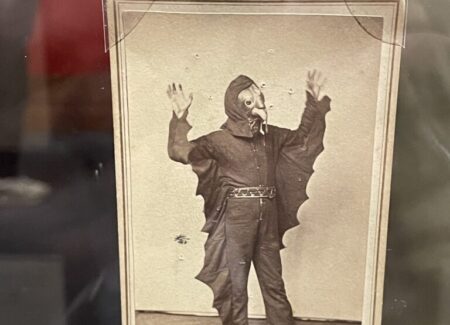

When the tintype became available in the 1860s, while it gave up some of the exacting detail of the daguerreotype, it offered several important benefits – it was much cheaper, it was easier and quicker to produce (allowing portrait studios to move into tents, booths, and other temporary locations), and it was more lightweight and durable, given its thin metal backing. These improvements proved to be important for American photography adoption, leading to an explosion of interest in the inexpensive image-making technique. Schaeffer’s collection of tintypes offers evidence of this expansion in demand, most particularly in the form of much more eclectic and eccentric portrait making – when it became cheap to make a photographic portrait, Americans jumped at the chance to show off their individuality. Suddenly it was more possible for salesmen, workers, children, elders, families, and groups of people to have their portraits taken, and Schaeffer amassed prime examples of men with high-wheeled bicycles, photographers with cameras, and even a man with a pet squirrel. With the addition of applied color and multiple exposures, the possibilities for caricature and visual trickery opened up, adding a sense of playfulness and personal pride that feels uniquely American.

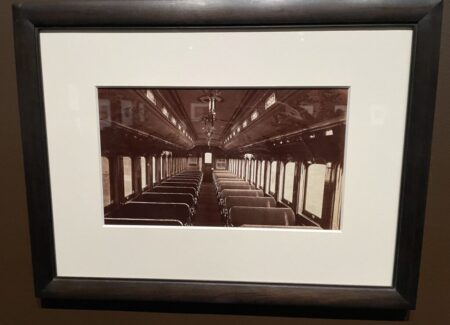

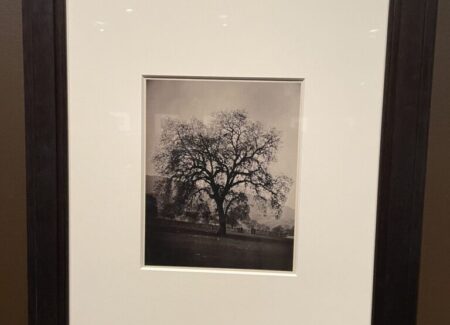

The middle section of the exhibition moves on to paper prints, largely albumen silver prints, with the Schaeffer acquisitions quietly augmented by some other choice inclusions. Process-wise, there is another round of technical innovation, with larger high quality prints now possible with a paper substrate. This led to a move outside the studio, to use photography to document the grandeur of the American land, its booming cities and railroads, and its Civil War; the paper processes also allowed the flourishing of more self-consciously artistic aesthetics. As seen in the selections here, more notable names have found their way into the flow of the curatorial narrative, including a lovely snow scene in Boston by Josiah Hawes, a towering California oak “portrait” by Carleton Watkins, an early view of Albuquerque by George Bennett, and an image of the reconstruction of Atlanta after Sherman’s march by George Barnard. But the broad democracy of vision that had been embraced after the arrival of the tintype is still very much in force, in pictures of landscapes, locomotives, tennis players, bridges, windmills, displays of apples, and a “welcome” arrangement made from fern leaves.

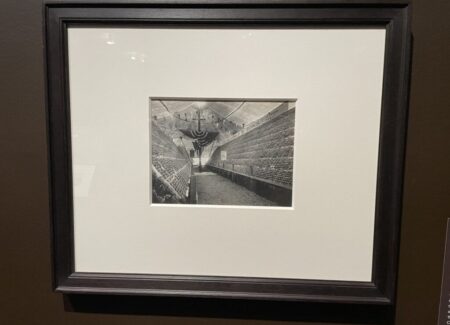

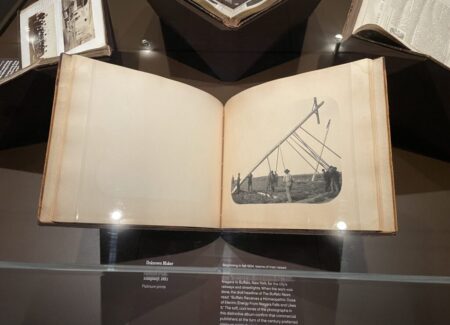

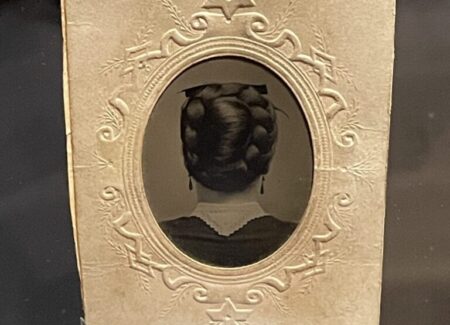

Once the albumen on paper revolution happened in 19th century photography, the next set of innovations came in form factor – the carte de visite (a small roughly 4×2 inch paper image, easy to share, send, or exchange), the cabinet card (a somewhat larger 4×6 inch card), and the stereograph (a paired set of 3×3 inch square images mounted on the same card, creating a subtle 3D effect when seen through a stereo viewer). The last room in the show gathers together Schaeffer collection examples of all three of these photographic mediums, and once again, with the lowering of price and the expansion of distribution possibilities, the quirkiness of America’s vision of itself becomes even more visible. In another exhibition design success, the Met has displayed the intimate cartes de visite sandwiched between vertical sheets of clear plastic, arranging them in tight grids and making them visible from both sides. The sheer diversity of personalities and ideas is what sticks out here: soldiers, carnival workers, musicians, Native Americans, miners, a man in drag, another wearing mittens, a third in a bat costume, a woman’s braided hairstyle, a frog (cleverly titled “A Politician”), several dogs, a roller skate, and one very large meteorite. With a little more visual space available in the cabinet card, a bit more context can help tell the story of a trapeze swinger, a wallpaper hanger, an electrical lineman, a Civil War veteran in a wheeled cot, and a man lying on a roof. And the stereographs are particularly successful at capturing complex interiors and landscapes, where the appearance of dimensionality draws the viewer deeper into the scenes, as a vehicle for armchair travel. A quick scan of the views is like a whirlwind tour, from the Dakotas and the Rocky Mountains, to California, and back through the Mississippi River, and once again to Niagara Falls, with a few visual detours to show us huge hailstones, bricks of silver, and the moon.

There is a definite rule-breaking energy to this show that cuts across any biases viewers might have against the “antiqueness” of 19th century photography. What Schaeffer’s collection does is celebrate American curiosity and individuality, embracing different early forms of image making and using them to tell an inclusively wide range of stories of who we were (and are) as individuals. More self-promotion than artistic intention, the collected works are resoundingly filled with possibility and potential, leaving us with a thought-provoking set of questions about what it meant to choose to photograph something, someone, or even oneself at that particular moment in American history. Today we take that impulse for granted, as we are all makers now; back then, it was even more of a confident declaration of independence. In this way, The New Art buoyantly expands the definitions that we typically use to bound our understanding of 19th American photography, making room for those unconventional many among us who never considered themselves artists, but still wanted to tell their own stories.

Collector’s POV: Given the large number of makers, known and unknown, included in this show, we will forego our usual discussion of individual gallery representation relationships and secondary market histories.

The MET’s press release for the Maritz promised gift of Schaeffer’s collection is dated Jan. 3, 2020, not 2000.

Thanks for catching that typo. It’s been fixed.

I think you could have busted out that third star for this exhibition.