JTF (just the facts): A group show of 76 works by 26 artists, variously framed and matted, and hung on light and dark brown walls in the five ground-floor print rooms at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. The exhibition was curated by Sarah Greenough and Andrea Nelson. A special exhibition website can be found here.

The exhibition is divided into five named sections: Traces of History, Time Exposed, Memory and the Archive, Framing Time and Place, and Contemporary Ruins. The following photographers/artists are represented in the show, with the number of works on view, their processes, and associated dates as background:

- Uta Barth: 3 inkjet prints, 2011

- Matthew Brandt: 1 salted paper print, 2007

- Sophie Calle: 2 framed inkjet prints, 2010

- Chuck Close: 1 daguerreotype, 2007

- Linda Connor: 4 gelatin silver prints, 1893/1997, 1895/2002, 1903/2002, 1955/1996

- Moyra Davey: 10 chromogenic prints, 1990/2010-2011

- Binh Danh: 3 daguerreotypes, 2008, 2011, 2012

- Adam Fuss: 1 daguerreotype, 2012

- Myra Greene: 7 ambrotypes, 2007

- Miyako Ishiuchi: 2 gelatin silver prints, 2001/2014, 2002/2014

- Idris Khan: 1 digital silver bromide print, 2012

- Deborah Luster: 3 gelatin silver prints, 2008-2011

- Vera Lutter: 3 gelatin silver negatives, 2008

- Sally Mann: 9 ambrotypes, 2006-2012

- Chris McCaw: 1 pair 2 gelatin silver paper negatives, 2011, 1 set of 13 gelatin silver paper negatives, 2011, 1 gelatin silver paper negative, 2012

- David Maisel: 2 inkjet print, 2010/2011

- Christian Marclay: 1 cyanotype, 2009

- Susan Meiselas: mixed media installation, 1979-2009/2014 (including 2 matchboxes, 1980; 1 tear sheet from Swedish magazine, c. 1981; 15 slide transparencies in a plastic sleeve, 1979; 1 gelatin silver contact sheet, 1979; chromogenic prints, 1979, 1982, 1983, 1986, 1991, 2009; Quick time video excerpt from the film Reframing History by Susan Meiselas and Alfred Guzzetti, 2004)

- Andrew Moore: 2 inkjet prints, 2008/2014, 2009/2014

- Alison Rossiter: 2 gelatin silver prints, 2010, processed with Eastman Kodak Azo Hard C Grade, expired November, 1917

- Mark Ruwedel: 1 set of 12 gelatin silver prints, 1995-2004, 1 set of 4 gelatin silver prints, 2007-2010

- Hiroshi Sugimoto: 2 gelatin silver prints, 1993

- Mikhael Subotzky/Patrick Waterhouse: 1 light box with 810 color transparencies, 2008-2010; 1 light box with 484 color transparencies, 2008-2010

- Carrie Mae Weems: 2 chromogenic prints, 2002/2013, 2002/2015, 1 set of 17 inkjet prints, 2010

- Witho Worms: 2 carbon prints, 2007, 2008

The exhibition is accompanied by a catalog published by the museum/Thames & Hudson (here). The book (hardcover, 10 x 11 inches, 162 pages, with 130 four-color reproductions, $50) was edited by Sarah Greenough. She is also contributor of the introductory essay, with commentaries on individual photographs by Andrea Nelson, Sarah Kennel, Diane Waggoner, and Leslie J. Ureña.

(Installation shots below.)

Comments/Context: The National Gallery of Art is burdened, even more than the Met or the Getty, with being an institution that the American public relies on to defend time-honored aesthetic values.

Let NYC and L.A. identify trends in performative erotics and iron out the latest wrinkles in post-post Modernism. Better that the NGA move deliberately, its collections accruing at a stately pace. Our federal elite surely believes, although seldom is so crass to declare outright, that the country’s national museum of art should behave—on the analogy of the fictive origin story for our bi-cameral legislature—more like the Senate than the House. (Asked by Thomas Jefferson why the country needed both deliberative bodies, George Washington is supposed to have said: For the same reason we need a saucer beneath a cup of hot coffee. Unless passions are allowed to cool, they can be injurious to public health.)

This exhibition and catalog are designed to alter the NGA’s reputation for stodgy conformity. For the first time in its history, thanks to money from the Alfred H. Moses and Fern Schad Fund, the museum over the last eight years has had a budget with which to buy contemporary photographs.

If Sarah Greenough and her staff have not entirely dispelled the NGA’s image for moral caution—nothing here would give Ted Cruz conniptions if he strolled by—the curators have nonetheless produced a survey different from the sort too often found these days in museums from Seattle to Cologne. The selection has a thematic unity, with a neo-Romantic stress on mortality and decay, and the photographers are a diverse lot who have not all been vetted by eminent critics or the art market.

There are no Pictures Generation artists, for instance, and no Germans. The marquee’s biggest “names” are Chuck Close, Hiroshi Sugimoto, Carrie Mae Weems, Sally Mann, Sophie Calle, Vera Lutter, Susan Meiselas, Uta Barth, Andrew Moore, and Adam Fuss. What’s more, none of these figures are treated with more pomp than lesser-knowns Myra Greene, Witho Worms, Miyako Ishiuchi, Binh Danh, Deborah Luster, Chris McCaw, Alison Rossiter, Moyra Davey, Mikhael Subotzky and Patrick Waterhouse, Idris Khan, and Mark Ruwedel. Almost half the works on the walls are by women.

I’m guessing such unorthodoxy was dictated both by financial constraints (a Prince, a Sherman, a Gursky, and a Demand might have drained the yearly outlays of the Moses-Schad Fund) as well as by a wish to break with the herd and present a group of related works in depth.

Divided into five chapters—“Traces of History,” “Time Exposed,” “Memory and the Archive,” “Framing Time and Place,” and “Contemporary Ruins”—the show is loosely built around the idea that photography itself is not a neutral and value-free recording system but instead is subject to the same historical forces that we see when we look back at people, places and things in old photographs and daguerreotypes. Anxiety about relentless and disorderly change, of eras at an end and of the past in flux—always disappearing at a faster rate but also, to paraphrase William Faulkner, never really past—has become particularly acute in the digital age as once-standard tools for picture-making have in the last 15 years become obsolete and new tools for storing, recovering, and recycling everything are easier to come by.

Much of the work here comments on the pendulum of time as an invisible wrecking ball and on the checkered history of America as reflected in photography. Artists have highlighted its properties as a light activated, time-based process that has moved through several technological phases before the present, and this historical self-consciousness helps to cut through the nostalgic air that inevitably hangs over the show.

Since the 1970s sectors of the art and photo community have expressed affection for outmoded processes, alternatives to the hegemony of straight photography. Catherine Reeve’s The New Photography: A Guide to New Images, Processes, and Display Techniques for Photographers (1984) was a popular how-to guide, with tips on gum bichromate, cyanotype, and salt paper printing as well as xerography and holography. More recently, the critic Lyle Rexer’s Photography’s Antiquarian Avant-Garde: The New Wave in Old Processes (2002), noted that many of today’s young artists were moving forward by looking back to the 19th-century origins of the medium.

Two other U.S. exhibitions have taken note of this movement: Light, Paper, Process: Reinventing Photography, curated by Virginia Heckert, is now at the Getty through the first week of September, and Photo-Poetics: An Anthology, curated by Jennifer Blessing, goes up in November.

What distinguishes In Memory of Time is its concentration on social issues. The first room includes daguerreotypes by Close and Fuss, and ambrotypes by Mann and Greene, while the second room has three negatives by Lutter from a camera obscura and McCaw’s burned negatives, scorched by the sun’s transit. None these works are quaint, however, and more than a few ask searching political questions about the bona fides of old-fashioned technology.

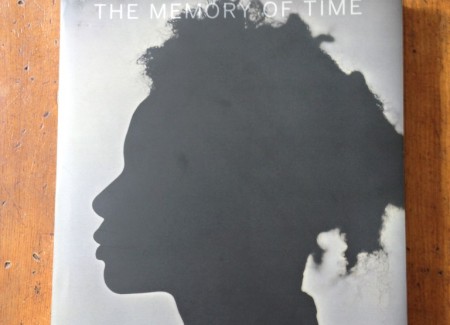

Close’s Kara (2007) is an ingenious portrait of the artist Kara Walker. His decision to photograph her in daguerreotype and only from the side, as a black silhouette, is both a nod to her own 19th century artistic revival of paper cut-outs and a reminder, in its “mug shot” view, that photography has served as a literal form of racial profiling. Walker adopted the paper cut-out to tell stories about violence endured by African-Americans. Silhouetting in her art equals stereotyping. Close’s removal of facial details is more benign: the tufts of hair at the back of her head signify that the figure in the portrait is an African-American. But by reducing her to a contour, the image also removes any signs of the skin’s aging. Walker was in her 30s when the picture was taken and could be mistaken for a teenage girl. Flatness has seldom had so many layers.

The somber tonal range of the ambrotype, which goes from pale gray to milk chocolate to pitch black, is favored by modern photographers wanting to set a subject in a sentimental mood. Mann strips the process down to something more primal. In her nine self-portraits, done between 2006-2012, as she was turning 60, she assumes a contrasting series of expressionist poses: a fierce she-wolf, eyes flashing; an androgynous observer, calculating and wary; a proud woman with fine bones and lines on her neck; and a soon-to-be ghost whose flesh and very skull are on the verge of liquefaction, leaving nothing but a pair of eyes. Her mid-career dedication to the collodion process is here justified by portraits that go farther into complex, unresolved emotions than anything she has yet done.

Greene teases out some unsavory associations with race from the ambrotype. Each of the prints in Character Recognition (2006-07) is a close-up of an African-American facial feature (mouths and noses, lips and teeth.) If done in digital color and posted on Instagram, these shots might be regarded as zany selfies. But as dark-hued ambrotypes, they call to mind the bloody 1850s, the decade before the Civil War, when the process was popular. It is uncomfortably easy to imagine a plantation owner or slave auctioneer showcasing his property in this manner. Tightly cropped and displayed like specimens in a glass case at the NGA, the prints could be the works of an oppressor whose camera wants only to classify in order to demean.

For Allegra by Fuss is a large-scale daguerreotype of the Taj Mahal. If the image looks antique, that’s because it is. The artist scanned three waxed-paper negatives of the structure taken in 1864 by John Murray, then digitally stitched them seamlessly together. Fuss has thus neatly fused three of the major photographic processes into one image.

As his subject is a monument built by an Islamic emperor, Fuss’s handiwork touches on photography as a colonialist tool that helped to exoticize a foreign land and justified its conquest. (Murray was English and so is Fuss.) But as the Taj was built to commemorate Shah Jahan’s grief for his deceased wife, and as Fuss’s title refers to a former inamorata, the image is also a reminder of the medium’s enduring role as an agent of memory, of love beyond the grave and of one’s youthful self. The bluish-gray cast of the daguerreotype, its exceptional size (23 ½ x 38 inches), and its multi-sourced heritage, removes this Taj from the realm of visual clichés. The building seems to hover off the ground in a temporal zone that is neither entirely past nor present.

Meiselas’s The Life of an Image: “Molotov Man,” is the only work in the show that originated in photojournalism. In 1979, during the early years of the Nicaraguan civil wars, she took a picture at a skirmish of an armed young man in a beret throwing a Molotov cocktail. A formal hybrid of Capa’s dying Spanish Civil War soldier and Che Guevara, he quickly became a reproduced symbol.

But as she discovered and illustrates here, the meaning of his gesture was ambiguous, depending who interpreted and appropriated the image. For the Left, he stood for inspiring resistance to Somoza’s dictatorship; while for the Contras and others on the Right, the bomb-thrower represented the threat of anarchy and terrorism in the streets. Each side adopted him for its own ends.

Meiselas multi-media installation is arranged like a treasure hunt. We follow the trail of the “Molotov Man” as he/it evolves over the years, appearing in news stories and posters, on walls and t-shirts, as silhouette and painted statue. In a 1990 filmed interview with Pablo Jésus Aráuez, the figure who threw the bottle explosive in 1979, we see him as a father with a young son clinging to his neck. These talking images don’t necessarily look less “real” than the flattened ones. Meiselas’s installation certainly suggests though that this man’s life would have been invisible, or at least unrecognized by the eyes of the world, were it not for photography’s unique ability to transform and aggrandize a gesture rebellion into an icon.

The two enormous tessellated color towers by the South African-British team of Subotzky and Waterhouse dominate the fourth room here. Doors, Ponte City, Johannesburg; and Televisions, Ponte City, Johannesburg, exhibited at the ICP Triennial in 2013, are documents, as their titles state. At the same time both are as sculptural as they are photographic. They glow like stained glass windows, made from hundreds of transparencies that are gridded and stacked like the housing blocks where the photos were taken. Whether these elaborate constructions exalt or falsify the lives of the people whose doors and TV shows are portrayed depends on how far away you stand from the light and how closely you care to look at individual cells.

By contrast, Ruwedel’s black-and-white prints are so plain and self-effacing that they look as if they wouldn’t dare ask for our appreciation. Westward the Course of Empire is a series of ironic landscapes of abandoned rail lines in the Western U.S. As little remains of these structures except curving humps of earth and grass and scattered stones, these photographs against flat horizons are symbols of human vanity that bring to mind Ecclesiastes, Ozymandias, Jamestown, Robert Smithson’s ruins, Indian burial mounds, and Rebecca Solnit’s book River of Shadows, which describes how 19th century photography and the railroad ran along parallel tracks. Many artists have surveyed the Western U.S. with large-format cameras since the Rephotography Project (Mark Klett, Ellen Manchester, Joann Verburg, Gordon Bushaw, Rick Dingus) of the 1980s. Ruwedel’s contribution to this tradition may be the most eloquent so far.

The show also has its share of duds. Ishiuchi’s contact prints of her late mother’s lacy lingerie may be redolent artifacts as keepsakes, but they aren’t compelling as photographs. Worms’s salt paper prints of slag heaps in Europe, created in part with dirt he collected from the sites, suffer from being too impressionistic in their brown gloaming to score against anti-strip-mining targets they aim at. Simon Starling did this better in One Ton II (2005), his platinum-printed photographs of the mine where the precious mineral was quarried.

Slow Fade to Black II by Weems is another misfire. She has rephotographed—out-of-focus—publicity portraits of 17 classic black female singers (Billie Holiday, Mahalia Jackson, Nina Simone, Marian Anderson, Ella Fitzgerald, Josephine Baker, Dinah Washington, among others), and mounted them in small frames–an effort, writes Andrea Nelson in the catalog, “to restore these performers’ presence in contemporary society.”

The artist’s misconception is on two levels. First, the assumption that these performers have faded from memory is hard to accept. Compared to 99.9% of all American singers dead for decades, almost everyone in this ensemble is still vibrantly alive on the radio, in the movies (features as well as documentaries), in history books and novels, and in the repertoires and conscious phrasing of living singers. Second, if you sincerely want to revive the memory of people you believe have unjustly faded from public view, why blur their faces so they are less recognizable to a potential audience?

Likewise, Marclay’s white skeins of sound recording tape, contact printed on cyanotype, originated in what must have seemed like a sure-fire idea: the marriage of two obsolete technologies. The picture fails, though, to create the necessary third thing: a picture that fuses their separate identities as antiques into something stranger, as Fuss does so well in his digital daguerreotype.

Davey’s microscopic close-ups of Lincoln copper pennies disclose about what you would expect: plenty of metallic wear and bacterial crud. (The urge to include a coin with a hole in the assassinated President’s head must have been irresistible. I wish she could have resisted.) Rossiter’s numinous black-and-white abstractions, made from film that expired almost a century ago, are automatically of interest, like photos from a pinhole camera. Oddly, that may be a problem going forward. Despite the fact that each roll of film is unique so that any pictures that result from exposure are unpredictable, they are suffused with a uniformly gothic atmosphere. If The Memory of Time has a weakness, it’s a tendency to be overly impressed by poetic effects.

These complaints should not deter visitors from heading to DC during the survey’s last month. As evidenced by the confluence of exhibitions by artists recycling the historical materials of photography and rethinking its basic properties, back-to-the-future is where we’re headed at the moment. The NGA and the Getty are not usually museums one visits to find out what’s happening in the contemporary realm of anything. For the next few weeks, however, they’ll be where it’s at.

Collector’s POV: Since this is a museum show, there are of course no posted prices. As such, and due to the large number of photographers included, we will dispense with the discussion of current prices and secondary market histories usually found here.