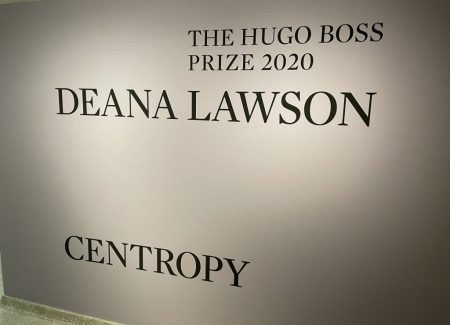

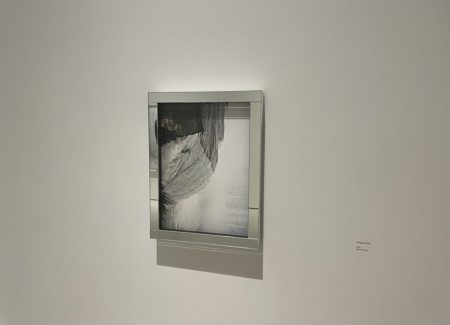

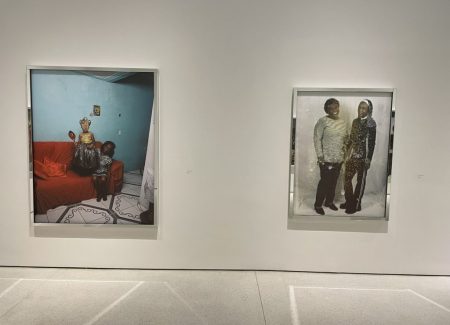

JTF (just the facts): A total of 19 photographic works, displayed against white walls in a single gallery space on the 7th floor of the museum. 14 of the works are pigment prints in mirrored frames, made between 2013 and 2021. 3 other works are also pigment prints in mirrored frames, but 2 have the addition of embedded holograms, and the third has a small glossy print tucked into the frame edge. In one corner of the gallery space and along the edge of the wall near the elevators, a work made of UV printed mirrored glass and rose quartz on mirrored glass, from 2020, has been installed. In the center of the gallery, a hologram, from 2021, sits on a pedestal, and rock crystals can be found in two corners of the gallery space. The exhibition was organized by Katherine Brinson and Ashley James. (Installation and detail shots below.)

Comments/Context: In the past decade, Deana Lawson’s artistic star has undeniably been on a steady rise. After being included in MoMA’s New Photography series in 2011, she won a Guggenheim Fellowship in 2013, and has since worked her way through a solid run of museum and gallery solo shows, and published her first monograph with Aperture.

Along the way, her approach has continually evolved and matured, and the consistency of her image making has improved. Her last gallery show in New York (reviewed here) was populated by a handful of standout images, including a daringly unsettled portrait of two young Black men on a couch (one with a gold grill pulling open his mouth, that is then rebalanced by an insert of George Washington’s wooden teeth), which to my eye was one of single best contemporary artworks (in any medium) made that year. This smartly edited presentation of her recent work builds on that momentum and is similarly filled with durable knockouts.

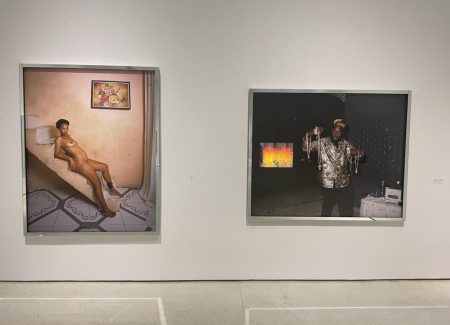

Lawson’s unique approach to portraiture has now become something of a visual signature – her photographs have power and presence. At first glance, many of her pictures of Black women, men, couples, and multigenerational families look almost like enlarged snapshots plucked from a family album – between the casual poses and the unassuming interiors they seem to document, the images initially feel like quick takes. But then Lawson’s deliberate sense of control starts to come through, her large format camera capturing scenes that have actually been meticulously arranged and composed. Her subjects might be friends and family, or they might just as well be strangers gathered from around the world; the rooms might be someone’s home, or carefully staged versions of such a place; and the mood is often infused with intimacy and familiarity, but also uncertainty. Lawson’s photographs tell open-ended single frame stories, and her visual storytelling has become sharper, more enveloping, and more sophisticated in recent years.

Many of the photographs in this show trace the cycle of life, largely through portraits of women. Lawson offers us a range of images of confident young women (generally posed nude, Daenare with an ankle monitor as her only adornment, and another group of three Axis aligned to highlight their different skin tones), and then moves forward in time to a wedding (the woman covered in dollar bills), pregnancies, motherhood (women posed with toddlers and then older children), grandmotherhood, and ultimately death (in Monetta Passing, a grimly startling image of a wake). Lawson’s sparse compositions center our attention on the subjects, and a small number of paintings, sofas, and other items of room decor that provide potential clues to broader identities. But mostly, it is the subtle facial expressions that create the genuine vitality in these pictures – flashes of self-assurance, strength, joyful pride, weariness, protectiveness, support, responsibility, and a host of other nuanced roles and emotions all make appearances. Seen together, the images offer a much more complex view of the real span of Black female identities than we often see in contemporary photography.

In this particular edit of Lawson’s recent work, there are less men included as subjects, but when they do appear, they too inhabit different forms of Black masculinity, from shirtless young men and hustling street corner entrepreneurs to husbands, fathers, and devoted widows. Diaspora legacies provide a backdrop to her excellent image Chief, where a man sits on a sagging couch wearing a crown and heavy gold jewelry, surrounded by billowing curtains, and even in this modest setting, he still carries himself like a king.

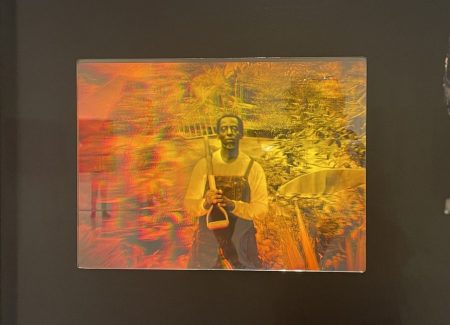

Several of Lawson’s images are visually interrupted in one manner or another, either by surface scratches or marks, distortions to the negatives, photographs physically attached to the edges, or embedded holograms. The holograms provide the most eye-catching additions, particularly in the case of the image Black Gold, where a man tries to sell gold jewelry, cologne, and other items from a makeshift table on the street, his dyed hair and shiny shirt completing the overall look. The golden hologram hovers in the space of the black night, its image of a slave in overalls with a pitchfork over his shoulder lingering like a ghost, drawing a resonant parallel between occupations and opportunities, past and present.

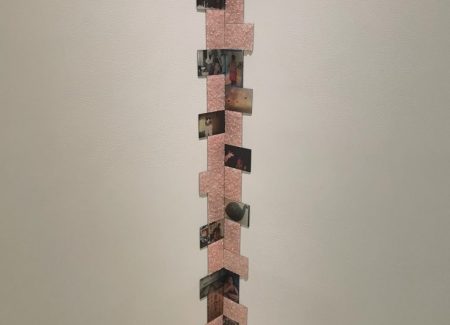

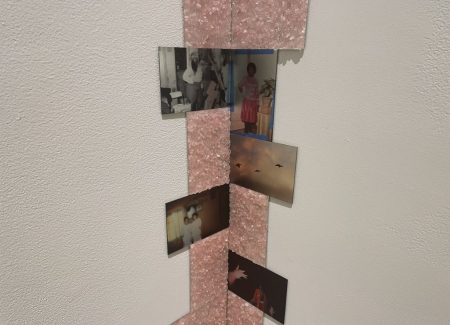

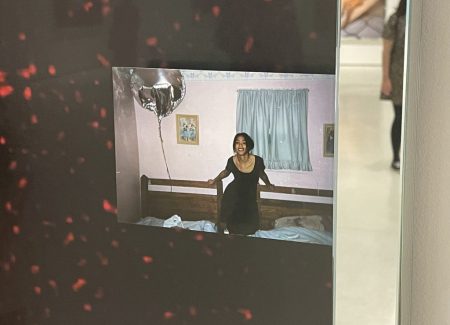

The rest of the works on view expand the conceptual horizons to a more mystical plane, where cosmic starlight is cut through by a dark horizon, waterfalls tilt sideways, and rock crystals cluster in the corners of the galleries. A central hologram offers a mathematical view of a torus, its inner tube shape seeming to close the circle begun by the photographs out on the walls, connecting everything together. Two installations of interleaved pink crystals and small photographs create a different kind of chronological progression, wandering through various life moments and linking them into a continuum. And Dana and Sirius B is another work that bridges between the celestial and the worldly, the massive pinprick of starlight decorated with an image of a smiling young Black woman with a silver mylar balloon, itself not unlike a shining moon in the sky.

This exhibit seems to mark the pivot point where Lawson has definitively transitioned from an early career photographer still finding her voice to a more mature mid-career artist who now has firm control of her ideas and aesthetics – she’s reached her power zone, and seems poised for a productive run. In her own way, she’s subtly reinventing photographic portraiture to better tell Black stories, and exposing veins of human richness and complexity that we need to see with more clarity.

Collector’s POV: Since this is a museum show, there are of course no posted prices. Deana Lawson is represented by Sikkema Jenkins & Co in New York (here), where she had a gallery show of similar material on view from March 8 to June 12, 2021 (here). Prices of those photographs ranged from $48000 to $55000 each, based on size. Lawson’s work has little secondary market history at this point, so gallery retail likely remains the best option for those collectors interested in following up.

Just saw this show and went in search of reviews.

Truly excellent, but surprised no mention of the antecedent of Paul Graham’s 2014 ‘Does Yellow Run Forever’, which portrayed the black female body in domestic rooms, in repose. These were intermingled with framed photographs of magical phenomena, rainbows for Graham, galaxies for Lawson. He photographed gold shops, she a gold seller. He used shiny gold frames, she used reflective silver-mirrored.

Really think her show is excellent, and hits every mark perfectly. But there’s a clear influence here, to my mind, that deserves to be acknowledged.