JTF (just the facts): A total of 42 black-and-white photographs, framed in black and matted, and hung against white walls in the two room divided gallery space. The show includes 18 gelatin silver prints by Robert Frank (in the front space) and 24 gelatin silver prints by Henri Cartier-Bresson (in the rear space). All of the prints are roughly 11×14 (or reverse). None of the Frank prints are vintage, while the Cartier-Bresson works are a mix of vintage and later prints. (Installation shots below.)

Comments/Context: Exhibitions that pit two or three artists in gladiatorial contests of styles and skills are understandably popular with audiences and a pain in the ass for curators. As instructive as it can be to compare treatments of similar subjects by a couple of masters, the problem for museums and galleries of finding salient material to underline a theme is compounded when multiple bodies of first-rate work must be secured. The deserved acclaim for MoMA’s “Picasso and Braque: Brothers in Cubism” in 1989 and “Matisse Picasso” in 2003 can be attributed in part to their already owning many of the paintings, sculptures and drawings and thereby not having to beg other institutions or collectors for loans. The upcoming “Degas/Cassatt” at the National Gallery of Art enjoyed similar advantages.

Head-to-head battles between world-class photographers have been infrequent events, perhaps because of these curatorial obstacles. But the proven value of the exceptions—Todd Papageorge’s exhibition and essay on the influence of Walker Evans on Robert Frank at the Yale University Art Museum in 1981; “Paul Strand and Ansel Adams: Native Land and Natural Scene” at the Museum of Photographic Arts in San Diego in 1991; and the Shelley Rice and Lynn Gumpert show and catalog, “Inverted Odyssey’s: Claude Cahun, Maya Deren and Cindy Sherman,” at the Grey Gallery in 1999—should have convinced other institutions to repeat the experiment.

Henri Cartier-Bresson and Robert Frank are ideal antagonists, with many of the same honors on their resumés and a shared empathy for society’s outcasts, but with unsettled personal tensions between them as well. Each produced a classic book in France at either end of the Fifties—“Images à la sauvette“ (“The Decisive Moment”) in 1952 and “Les Américains” (“The Americans”) in 1958—that inspired photographers around the world for generations. Both expanded upon an inherited documentary tradition and played by its rules. Their mutual allegiance to a 35 mm black and white aesthetic during the heart of their careers, when their paths sometimes criss-crossed in the U.S. and Europe, holds the promise that a side-by-side study could detect patterns less visible in solo retrospectives.

Their personalities, however, were not compatible. Fourteen years older, Cartier-Bresson grew up in a wealthy and cultured household and became a cosmopolitan renegade who leveraged early acclaim into steady employment as a globe-trotting left-wing photojournalist. Frank’s family was also financially comfortable. But as a Jew in Switzerland during World War II, he experienced insecurities and a small-country artistic horizon that led him to emigrate to the U.S. after World War II. Never at home anywhere, he has remained a loner, with scant interest in cultural politics or political cultures.

Friction between the two men at times erupted into public enmity. Frank suspected that Cartier-Bresson blackballed him from joining Magnum in the 1950s and on more than one occasion dismissed his rival’s post-WW2 photojournalistic endeavors. “He traveled all over the goddamned world, and you never felt that he was moved by something that was happening other than the beauty of it, or just the composition,” he said in a 1975 interview.

This throw-down exhibition at the Danziger Gallery—the first time these two giants have squared off and had equal billing, according to the press release—openly favors Frank. Not only does the Swiss-American-Canadian have priority of place here—all of his works being arrayed in the first gallery when the younger artist should logically follow the elder—but the simplistic dichotomy also makes Frank the lovable underdog. Who wouldn’t cheer for sincerity and sentiment over cold-blooded cerebration? It’s not a fair fight. (The show doesn’t help matters with the confused grammar of the title and subtitle: the order of the names would lead one to expect that Cartier-Bresson represents “Heart” rather than “Head,” when the reverse is supposed to be the case.)

Of course, galleries have to go with what’s available to them. They seldom have the luxury of museums, which can search the globe for perfect prints. The ones here by Frank come from a single source, the Pennwick Foundation. Even though Cartier-Bresson has more photographs on the walls, they were assembled from several collectors and only a few date from his greatest period of activity in the early 1930s. He is represented by pictures from over a longer time (1932-1966) compared to Frank (1948-1962), and many of those are the clichés, such as “On the Banks of the Marne” and “Behind the Gare Saint-Lazare.”

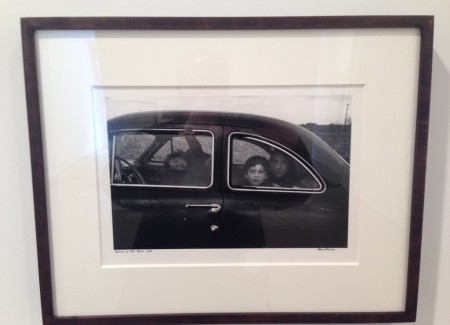

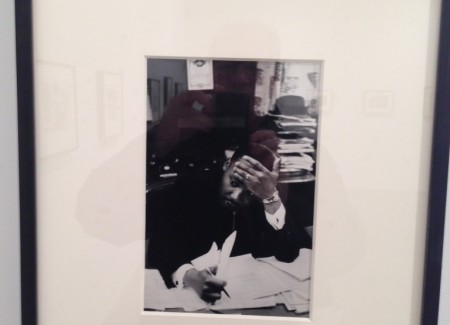

Although neither artist is known as a fastidious printer, the material from Frank is less familiar. Among the unexpected beauties are an Atget-like apposition of a stone pillar and an advertisement for Baumann top hats along a Zurich promenade (1952); a view from a NYC bus of a woman in a doorway (1958); a close-up of a Welsh miner as he lifts a white tea cup to his coal-stained face (1951); and the back of a man in overalls sitting at a Cleveland lunch counter, his fedora perched on an adjacent stool (1955). Frank’s pictures of people and their headgear in the 1950s could an outstanding show in itself. Only three of the prints are from “The Americans” and the outtakes (of Frank’s wife and two children in a car, 1955; of downtown NYC as seen from a car through the metal beams of a bridge, 1954) are as good as anything in the book.

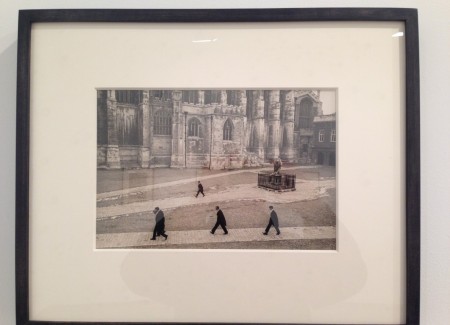

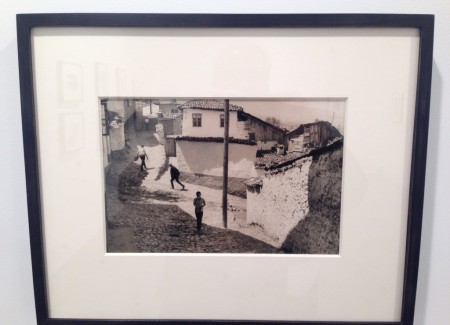

By contrast, according to the opposition of this show’s title, Cartier-Bresson is certainly the more removed observer. When he photographs a cluster of people in Aubenas, France standing on a set of steps and listening to an unseen Charles de Gaulle, it’s a deft comedy sketch. Their large scruffy dog has turned its head away, as though bored by the speech. The geometry of the scene—the dots on the women’s dresses and the dark slice of the man’s beret—are likely what caught the artist’s attention when passing by. This 1961 photograph and others—of dark-suited students walking along diagonal paths in the yard at Eton (1962) or women spreading saris beside the river in Ahmedabad (1966)—are characteristic of late Cartier-Bresson, after he had become a professional photojournalist. But they don’t reveal how savage (and moving) his pictures could be when he was a young man moving around Europe during the Great Depression.

A more illuminating show would match prints from the 1930s against Frank’s from the 1950s; and a more just presentation would have mixed them on the wall instead of confining them to separate room. As the photographer Greg Benson noted in a 2010 blog entry about Frank’s put down of Cartier-Bresson (here), it can sometimes be hard to tell the two apart without labels.

The faulty execution here should not deter others from trying to improve on what is a welcome idea. As a supplement to the art world’s diet of bloated retrospectives, a series of smaller, carefully researched two-person shows—Walker Evans and Helen Levitt, Robert Frank and Garry Winogrand, William Klein and Shomei Tomatsu, Robert Adams and Lewis Baltz, Peter Hujar and Robert Mapplethorpe, Bruce Nauman and Gary Hill, or even Eugène Cuvelier and Ansel Adams—might be healthy for both the eye and the heart.

Collector’s POV: The works in this show are priced as follows. Frank’s prints range from $18000 (“Hoboken, New Jersey,” 1955) to $195000 (“London, Bankers,” 1951), while Cartier-Bresson’s works range between $12000 (“Bolshoi Ballet School, Moscow,” 1954) and $22000 (“Valencia, Spain,” 1933). Both photographers are well represented in the secondary markets, with perhaps more Cartier-Bresson later prints floating around and giving him the advantage of sheer volume. Recent prices for Frank’s prints have ranged between $5000 and $600000, while Cartier-Bresson’s prints have generally ranged from $1000 to $200000.

I’d like to see Eugene Cuvelier and Robert (not Ansel) Adams paired for a show together.